With Christine Ward, veterans representative for Rep. Steve Knight, R-Calif.

LOS ANGELES–When Felix Jamison Sr. was born, the United States had not yet entered World War I, and when he enlisted 24 years later, the U.S. had yet to join in World War II.

When World War II ended, Jamison, the descendant of slaves, had attained the senior non-commissioned rank of master sergeant.

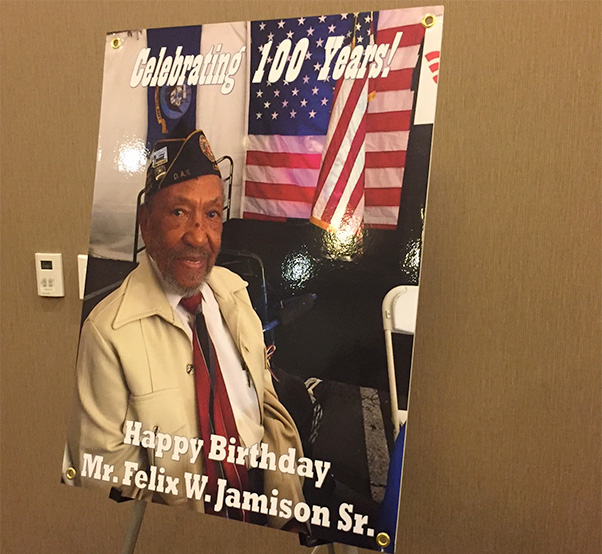

Jamison, born 100 years ago, celebrated his centenary birthday Dec. 10, at Bob Hope Patriotic Hall, surrounded by dozens of family members, some of whom traveled from points as far as Denver and Chicago to honor their elder.

Beside the extended family of children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and a few great, great grandchildren, Jamison, the grandson of Americans born into slavery, Jamison was saluted by a senior member of Congress.

“Listen to this man,” Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif. said. “He has such clarity, such possession. I could listen to him all day long.”

And seated beside him in the banquet chamber at Bob Hope Patriotic Hall, she nearly did. The pair spent his birthday in continuous conversation as the World War II veteran pointed out relatives and shared their stories with Waters.

He also received congratulatory messages from Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, from Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, and a flag flown over the nation’s capitol presented by Christine Ward, representing Jamison’s congressman, Rep. Steve Knight, R-Calif., a fellow Army veteran.

“Mr. Jamison is one of our heroes, and Congressman Knight recognizes heroes,” Ward said.

During his long career after the war, Jamison has also become something of a hero to other veterans. He has held administrative posts as commander and district officer in the Disabled American Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the American Legion.

“Felix has been in our post for 62 years,” said Vietnam War veteran Ronnie Baker, with Post No. 5 in Los Angeles County. “He would be there for every meeting early, and he comes in an Access bus (for handicapped passengers), and brings his walker.”

With Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif.

“It’s just an honor to see all this man, this soldier, has accomplished,” said another Vietnam War veteran, Mike Bertell, president of the Point Man talking therapy group of the Antelope Valley, the Los Angeles suburban community where Jamison resides.

Jamison said he enlisted in the Army in 1940 to move up and away from his home state of Louisiana, still mired in the segregation of post-Civil War south. The United States Army was also segregated, but Jamison determined to make the most of the opportunity he saw in the Transportation Corps, combat support trucking.

He moved up and served as a trainer of truckers who would eventually make their reputation in the European Theater of Operations as the “Red Ball Express.” But his war would be serving under MacArthur, in campaigns in New Guinea, and the liberation of the Philippines.

It is less remembered as the invasion of Leyte in present times than the historic moment during World War II when Gen. Douglas MacArthur waded ashore in the surf of the Philippine Islands to announce “I have returned.”

For MacArthur, it was the culmination of his vow that he would return after Japan invaded the Philippines after Pearl Harbor.

The forces of Imperial Japan seized Corregidor and Manila, took thousands of American and Filipino POWs and sentenced them to the Bataan Death March, a captivity that ultimately killed and caused the death of thousands.

The Japanese imposed a harsh rule that prompted Filipinos to initiate a guerrilla war against their occupiers that lasted for three years until the return of MacArthur and American forces.

For Jamison, rolling ashore on Leyte in a 6×6 truck onto the invasion beach was the culmination of all the training he had endured, and all the training he meted out.

Jamison led troops with the 3670th Combat Quartermaster unit, an all-black unit that rolled supplies – mostly bullets – to the troops under fire in the front line.

With Vietnam Veteran Ronnie Baker with DAV plaque.

“To get those bullets delivered, you had to get pretty close,” the former first sergeant recalled. “My truck was the first 6-by-6 onto the beach at Leyte.”

That was late in the morning of invasion day, Oct. 20, 1944, the first phase of retaking the Philippine Islands from the Japanese. By early in the afternoon, MacArthur would wade ashore, announcing to a coterie of military press that he had kept his promise.

In an interview at a recent veterans gathering, Jamison said he learned how to drive early because his father had a lumber business that spared the family from working on plantations.

Because of that business, Jamison had a driver’s license at a very early age, a license for driving a big truck. So, when he enlisted in the Army about a year before Pearl Harbor, the Army put that license and the driving experience that went with it to work.

“After I got my training, I became a drill sergeant, then a training sergeant, then a first sergeant,” Jamison recalled.

By the time he arrived with his unit in a Landing Ship Transport, he was in his late twenties – one of the “older hands.” They disembarked in Australia, and went on to run resupply in New Guinea, Hollandia – the Solomon Islands – and then, onto the recapture of the Philippines.

“When that big landing barge opened, my C.O., who was a good man, didn’t want me to go first to the beach,” Jamison recalled. “It was hot, and he didn’t want me hurt. I told him I had trained these men, and because I was the one that trained them, I had to go.”

The retiree, who resides in Palmdale, looks years younger than his actual age.

Jamison said he has kept his outlook on life optimistic despite living through years of segregation in the Army and the pre-Civil Rights South.

“I determined early in life, as young as 9 years old, that I would try to understand life, and to understand life, I would have to be able to first understand myself.”

“When I left the Army after the war, we decided to move from the South,” he said, recalling the exodus of black Americans who traveled North and West to find work and opportunity.

With Dennis Anderson and Mike Bertell, veterans from Point Man Antelope Valley.

In California, he established his family in Los Angeles, where he worked first at North American Aircraft, and later for 30 years at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

“My Army experience is what made them promote me, and made me a supervisor,” he said.

Editor’s Note: Dennis Anderson was an Iraq War embedded journalist and Army veteran of the Cold War. He works as a clinical therapist with a veterans community outreach for High Desert Medical Group.