Sharing memories that seemed as fresh today as the events that happened nearly 30 years ago, friends and fans gathered in the Voyager Restaurant at the Mojave Air and Space Port Dec. 17 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the unrefueled and non-stop, around-the-world, record setting flight of the Voyager experimental airplane.

Gathered around packed tables, there was barely standing room (with a few guests sitting on the floor) as they listened to Voyager pilot Dick Rutan, his brother Burt, designer of Voyager, and the world’s first civilian astronaut Mike Melvill and his wife Sally Melvill, as they shared their memories of the historic flight. Voyager co-pilot Jeana Yeager was unable to attend the event.

“This is not a project where we went out and got a multi-billionaire to write us a big check, it was a whole bunch of very, very talented people that made this possible,” explained Dick Rutan.

Reflecting back over the years, Rutan said he doesn’t think the flight would have been possible if just one of those volunteers hadn’t shown up.

Sharing more of the emotional aspects of the adventure than they did the technical challenges, the speakers often took a moment to compose themselves as they recalled some of their biggest fears.

The Voyager had taken approximately six years to build and flight test. It had flown a total of 360 hours and 68 flights before the record setting flight. “Seven times it had a failure and couldn’t maintain altitude,” explained Burt Rutan, speaking about why he feared he might not ever see his brother alive again.

Designed for maximum fuel efficiency, Voyager had a featherlight, composite structure with thin skin and it bobbed like a canoe in rough water, even during light turbulence.

In 1978 Mike and Sally Melvill moved to Mojave to test the new aircraft that Burt Rutan designed and built. The Voyager was one of many creations that Mike had the honor — and challenge — to fly.

On Dec. 14, 1986, Voyager departed from Edwards Air Force Base. The Melvills and Burt Rutan flew as escort for Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager, about 300 miles out over the ocean. “It was very hard to say goodbye, not knowing if we would see them again,” shared Burt, holding back tears.

Flying out, Sally said at first she was more concerned about not being able to see land. It was the first time she and Mike had flown so far over the ocean in a private plane. After watching the Voyager’s wing tips scrape the runway during takeoff that morning and a few other problems, she said there were a lot of tears shed when they had to turn back as the Voyager left their view.

“We have never flown where we couldn’t see land, and these guys were going to be flying 95 percent over water,” said Mike. “To stay in that thing for nine days, I didn’t think we would ever see them again.”

In 1984, Rutan and Yeager wanted to fly the Voyager to the Annual Experimental Aircraft Association’s fly-in, in Oshkosh, Wisc. Navigating through the turbulent air of the Rocky Mountains, Rutan said he and Yeager could hardly maintain the aircraft and he was so fatigued that they had to land in Salina, Kansas.

“I was so physically beat and emotionally drained that I had to be physically restrained from chopping a hole in the wing and throwing a match on it — that is not a word of a lie — and then, I was going to take my pilot’s license and throw it in and take a train home — but Jeana talked me out of it,” shared Rutan.

After a good night’s sleep and a Kansas steak, he felt better and they made it to Oshkosh the next morning. With a huge welcome and much needed moral support, their spirits were lifted. They also received donations for avionics and a communication system.

California to Wisconsin was tough — how could they possibly make it around the world?

With the mentality and spirit that has come to personify flight test pioneers in Mojave, Rutan and Yeager knew it was a high risk journey, and they knew that taking chances was the only way to progress. Luckily, the public never had a reason to see the “death tape” that they made a few days before the flight — just in case. Two reasons for the tape: to insist that there should be no lawsuits if there was a crash, and to affirm that everyone who ever worked on the Voyager should be proud of their accomplishments, even if it ended in a disaster.

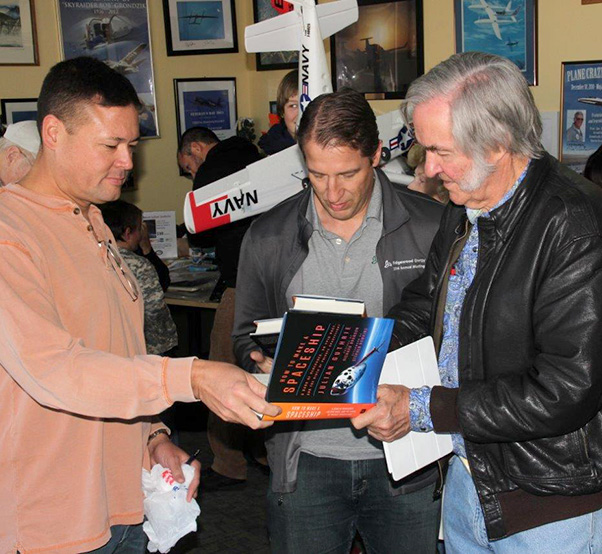

That evening they shared more of their story with about 400 guests at the Stuart O. Witt Event Center at a gala anniversary banquet, benefitting the Mojave Transportation Museum.

“Every time I listen to their story, I hear of a new detail, another part of the adventure,” said Cathy Hansen, founder of Plane Crazy and the Mojave Transportation Museum. “Imagine being locked in a phone booth for nine days while flying at speeds of only 80 knots — navigating around thunderstorms, near hostile countries threatening to shoot you down, worrying about whether or not you have enough fuel for the trip, running on one engine to conserve fuel and on the last leg of the flight suffering rear engine failure due to an air pocket in a fuel line, losing 5,000 feet of altitude while attempting to start the front engine?”

The flight around the world took off from Edwards Dec. 14, 1986, and lasted nine days, three minutes and 44 seconds. Tens of thousands drove out to wait on Rogers Dry Lakebed to welcome the adventurers home.

Previously awarded only 16 times in history, President Ronald Reagan presented the Voyager crew and its designer with the Presidential Citizenship Medal four days after their landing.

Today, Voyager proudly hangs in the South Lobby of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. “It is a great part of Mojave’s history,” says Hansen.

Plane Crazy Saturday is a free, family event held at the Mojave Air and Space Port every third Saturday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., with guest speakers share their stories. One-of-a- kind and vintage aircraft are on display along with memorabilia. For more information, visit www.mojavemuseum.org.