By Bob Alvis, special to Aerotech News

With all due respect to the rock group Pink Floyd, back in 1950 there were very few “bricks in the wall” known as the sound barrier. Today, a multitude of pilots have added their names to the fraternity of those that have gone supersonic, but let’s look back at when it was just a handful.

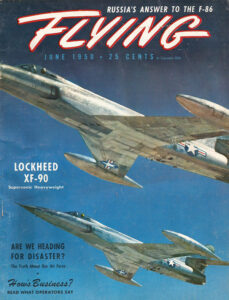

There was a time when every attempt was filled with drama — as we’ll see here, recalling the day when Tony LeVier nosed down his 13 tons of XF-90 for a ride he would never forget.

It was a sunny April morning in 1950 when LeVier prepared to join one of aviation’s most exclusive fraternities. The ceremonies required extensive preparations and paraphernalia for the initiation.

Lockheed’s chief engineer test pilot sat quietly in his seat at 40,000 feet. In front of him, the gauges for his two engines indicated 100 percent power and behind him, the two afterburners thundered into white contrails that stretched like a length of silky yarn across the blue California sky.

Some 50 miles ahead and below him lay the brown blot that was Muroc Dry Lake, where the engineering flight test crew listened to his breathing into a hot microphone and waited.

On this day, Tony was going to dive his XF-90 through the speed of sound. You could count on your fingers the number of men who been through that bogie — the sonic wall. Yeager had been through in a rocket ship. They think that Geoffrey de Havilland went through, but there was only a smoking hole in the ground in England where he had hit. No one would ever know for sure. But they did know that wall was tough.

Now Tony was going to try the needle nose of the 90 against it. According to all the wind tunnel dope, it should go through. LeVier was drawing test pilot pay to prove it. His speed had built up to more than 600 mph and the lake was near at hand. He started flipping switches that turned on the oscillography, audiograph, automatic camera and other instrumentation equipment.

“Lockheed remote one, this is 687,” he called. “Instrumentation is on, 100 per cent burner, all gauges steady, altitude 40,000 and I’m now pushing over.”

It’s pucker time, as Tony nosed down his 13 tons of airplane into a 60 degree dive. As his speed mounted, he quietly reported the behavior of the plane as it entered the transonic zone — the slight wing drop, the tucking tendency, then a slight rudder offset. He was in the wall. Then, like a greased platter, LeVier recalls it slipped through and he shouted through the mic, “There she is!” The Mach meter hand stood at one — the speed of sound — then moved on higher. The XF-90 was now traveling nearly 800 mph and the altitude was 27,000 feet. LeVier pulled back on the stick. “It might as well have been anchored in concrete,” he remembered saying. Tony was about to earn that test pilot pay for the day.

He flipped his stabilizer trim switch. Nothing happened. He stopped talking and all the radio men could hear was his rapid and heavy breathing.

On the ground, the engineering flight test crew watched the glint of the F-90 wings as it pushed over. At 20,000 feet, it entered a haze level and they could no longer see it.

Suddenly there were two tremendous explosions. Far out on the dry lake, a tower of brown dust plumed into the air. There was utter silence for a moment then a man spoke in an unbelieving voice. “My God, he dove in.”

What the test crew did not know was that Tony had started to reach for the dive brake handle when, ever so slightly, the nose of the 90 began to rise — and suddenly it swept up as the slow-moving trim tab took effect and the plane leveled off!

On the ground the flight test crew called the crash trucks. Suddenly, in what must have been a very surreal moment, Tony’s voice came back on the air and matter of factly stated that the plane had leveled out. “I’m coming home,” he said

The explosions the crew heard were the first sonic booms from a 13-ton F-90 and, by a bizarre coincidence, the dust plume was a practice bomb set off by the Air Force across the lake bed at the same moment.

This was the first of the 15 supersonic dives by the two XF-90 prototypes, a pair of fighters that Lockheed hoped would turn into a bread and butter post-war production airplane.

But during the decade following World War II, most fighters designed for the Air Force were destined to fail — and the XF-90 was no exception.

Tony Levier continued on and became the legend of Lockheed flight test, whereas the two XF-90s did not fare as well. One finished out its military service as a guinea pig when an atomic bomb was dropped at Frenchman’s Flat, Nev., in 1952, rendering the airframe useless. The other F-90 went less gloriously in 1953, when the Air Force ordered it shipped to the National Advisory Commission for Aeronautics laboratory in Cleveland. The orders simply read: “Ship by cheapest common carrier.”

Many thanks to the Sept. 15, 1955, Lockheed Star publication, that served as source material for this column.

Until next time, Bob out …