WASHINGTON, — War!

That was the headline screaming from newspapers around the country on April 6, 1917, as the United States declared war on the German empire.

The United States had avoided being drawn into what was then known as “The Great War,” which had been raging in Europe since 1914. But German unrestricted submarine warfare — which U.S. leaders regarded as war on civilians — led to this juncture. President Woodrow Wilson, who had just been re-elected under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War,” felt he had no other option.

Congress provided the then-astronomical sum of $3 billion to build a million-man Army.

“The United States was in it, but they had to define what ‘it’ meant,” said Brian Neumann, Center of Military History historian.

Neumann, who edited a series on the Army during World War I, said it wasn’t a done deal that Americans would go to France to help man the Western Front.

Various points of view

Some Americans believed that because a naval provocation led to the war, the proportional response would be a naval campaign against Germany. Others felt it was all right to help France, but not to help Great Britain, he said.

Still others believed that going to war had to mean something greater than simply returning to the status quo on the continent, Neumann said. They saw the war as an inferno that would topple empires so democracy and the will of the people could triumph. This was the camp that led.

“For the United States to have a voice at the peace table, it had to make a significant contribution to the war effort,” Neumann said. “That meant building an Army and engaging the enemy on the Western Front.”

Doing that was no simple task. On April 6, the U.S. Army was a constabulary force of 127,151 soldiers. The National Guard had 181,620 members. Both the country and the Army were absolutely unprepared for what was going to happen.

The United States had no process in place to build a mass army, supply it, transport it and fight with it. Continental European powers had a universal military service program in place, and when war broke out, reservists — already trained – went to their mobilization points and joined their units.

Large standing armies

Germany, France, Russia and Austria-Hungary had large standing armies and reserve formations in 1914 that the nations could call up in the event of a war. Great Britain maintained a robust naval reserve, but did not have a commensurate universal service reserve for its army.

“Britain and the United States didn’t see the need for universal service because of the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean. Those were two pretty good barriers,” Neumann said. “But after the war broke out, Britain began building its army.”

In 1917, Britain had an army of roughly 4 million soldiers, not counting the contributions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and the other parts of its empire. At its peak, the French army had 8.3 million “poilus” — as the French called their soldiers. The German army had 11 million under arms, the Ottoman Empire had 2.9 million, Russia had 12 million, and Austria-Hungary had 7.8 million.

The United States had to match that level of manpower.

What’s more, it had to be an American army. The United States did not formally join the alliance against Germany. Rather it was an Associated Power, which meant the United States would work with the Allies, but would be free to pursue its own strategic objectives.

Pershing takes command

Wilson and Secretary of War Newton Baker chose Army Gen. John Pershing to lead what would become the American Expeditionary Forces in France. Much of his time in France would be spent simply building — and protecting — the independent American presence in the country.

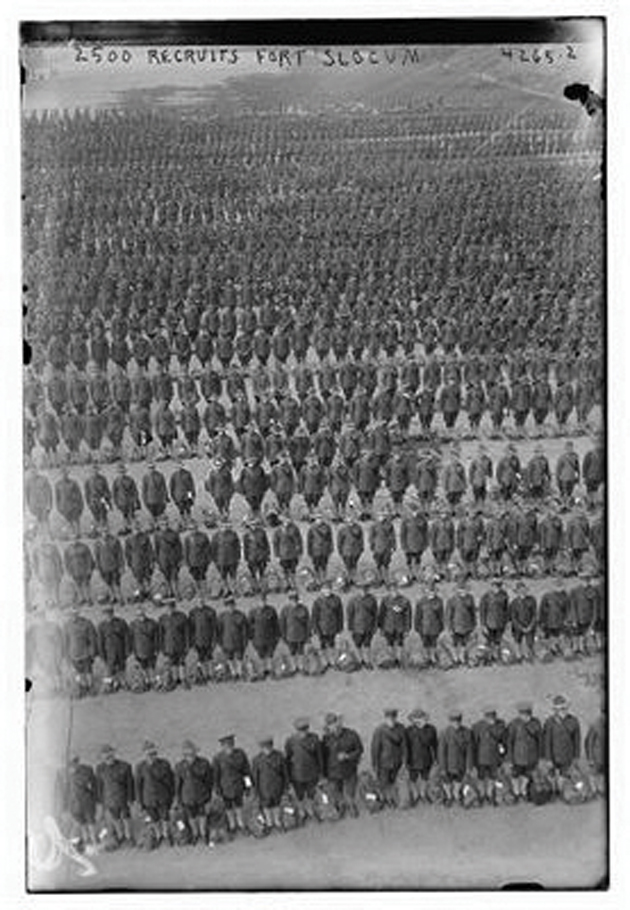

While many Americans rushed to recruiting stations and enlisted, the War Department recommended a draft to build what was called the National Army.

The Selective Service Act passed on May 18, 1917, and all men age 21 to 30 were required to register with local draft boards. Overall, 24,234,021 men registered for the draft, and inductees comprised 66 percent of those who served.

Army infrastructure

Pershing decided each American division would have four infantry regiments, an artillery brigade and ancillary units to allow it to function. Each would have 28,000 soldiers — about two to three times the size of British or French divisions. Desperate situation

By April 1917, a million soldiers in the French army had been killed. French soldiers had had enough, and about half of its infantry divisions refused to fight. These mutinies — which the Germans never found out about — caused the commander to resign and brought Gen. Philippe Petain, the hero of Verdun, to command of French forces. Petain, who collaborated with the Nazis in World War II, would rest the forces, grant leave and order no new offensives. His strategy “was to wait for the tanks and the Americans.”

This was the situation Pershing faced when he arrived in France on June 10. A cobbled together U.S. Army provisional division — which morphed into the 1st Division, “the Big Red One” – began arriving later in the month to a rapturous welcome.

And more would be coming. After surveying the strategic situation, Pershing sent a telegram to the War Department: “Plans contemplate sending over at least one million men by next May.”