There are fewer and fewer World War II veterans as the years roll along. The same plight is true of the Navajo Code Talkers whose living survivors are in single digits.

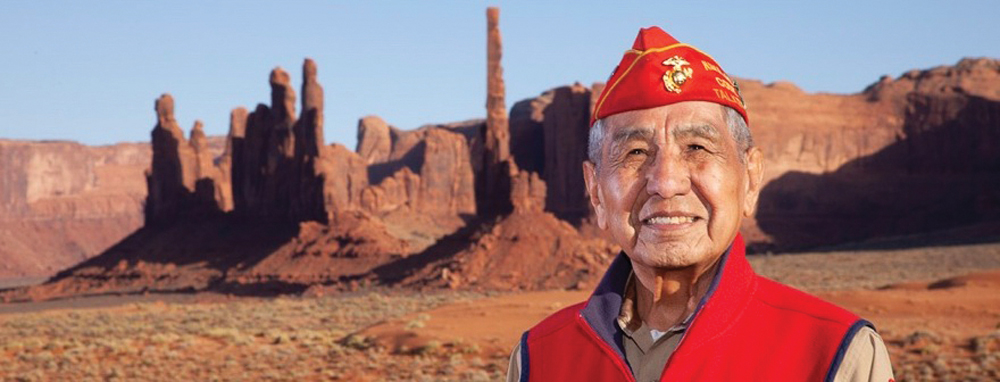

One of the last surviving code talkers delivered the keynote address at the Veterans Medical Leadership Council’s 17th Annual Heroes Patriotic Luncheon Nov. 8 at the Arizona Biltmore Resort in Phoenix.

Peter MacDonald, 90, a larger than life figure, took the audience on a trip of the origins of the Navajo Code Talkers and how they helped to win some of the fiercest and bloodiest battles in military history.

Not only that, he and his fellow code talkers were a secret weapon that was an instrumental part of winning the war in the Pacific.

He began his speech by thanking everyone who has served in the military. MacDonald served with the 6th Marine Division in World War II.

MacDonald said there was a serious problem with communications at the beginning of the war, and that the Japanese were breaking all details of every code. It would take awhile to persuade Marine officials that Navajo Code Talkers could profoundly help solve the communications dilemma.

Philip Johnson, a World War I veteran and son of a missionary couple, was raised on the Navajo reservation and spoke the Navajo language fluently. He proposed the use of the language to the Marines at the start of the war, MacDonald said.

Unfortunately, at the time Marine officials knew nothing of Navajo life and were afraid the Marines could be embarrassed. Finally, in April 1942 the idea was given the green light, and the formation of a code talker platoon became a top-secret project, he said.

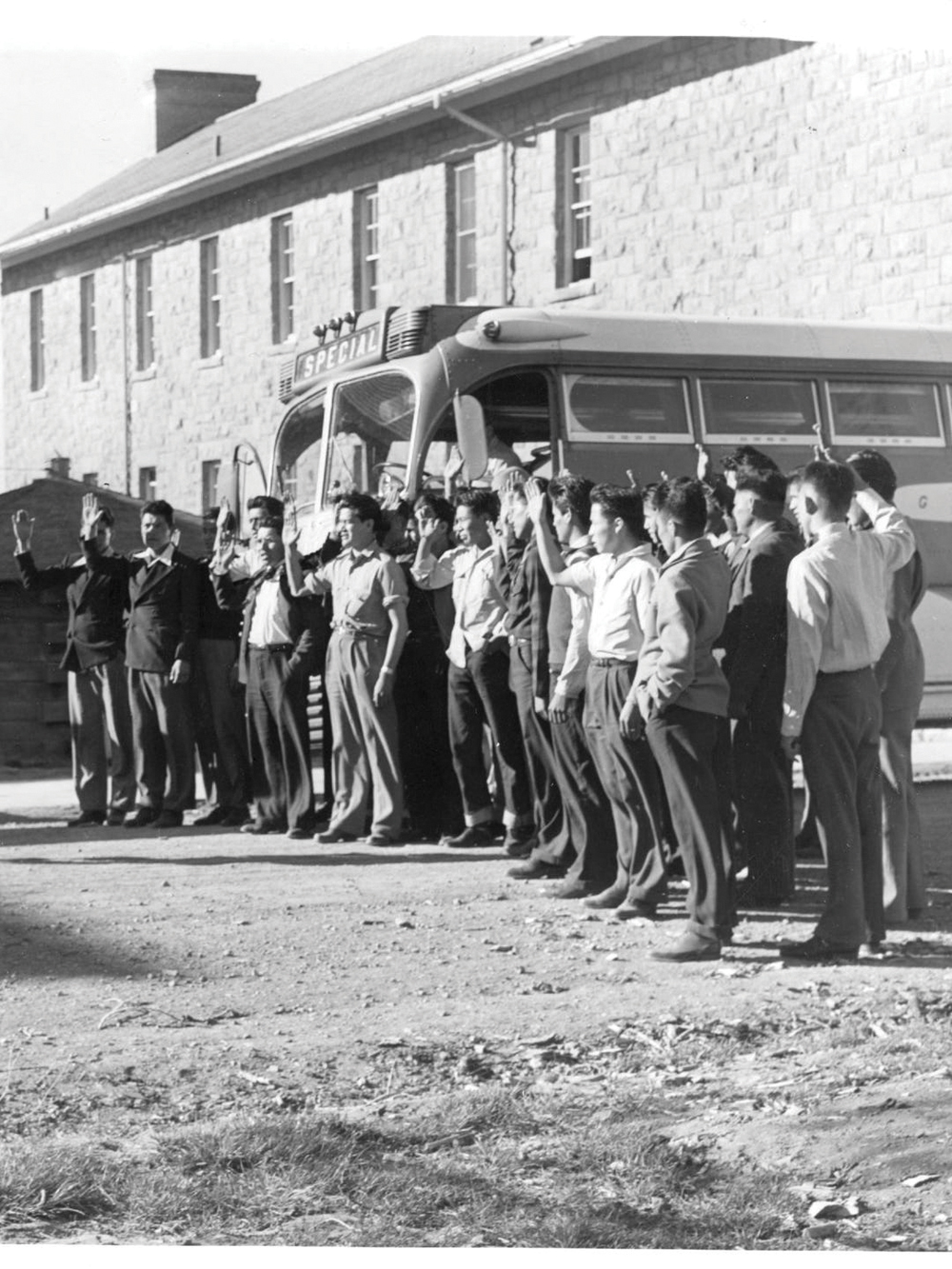

There were initially 29 Navajo recruits who attended basic training in May 1942. They were part of a separate platoon and were the number one platoon.

Part of the platoon’s training was learning the Morse Code and how to hook telephone wires to trees, but the highlight of what these 29 recruits achieved was the development of a military code.

“The code was subject to memory only, and we would be the only ones who knew the code,” MacDonald said. “Navajo wasn’t a written language, so we had to come up with our own words for the alphabet. Navajo words were selected to represent each letter in the English alphabet. Easy to remember words were chosen.”

However, he said another problem had to be solved and that was punctuation. Terms for punctuation were developed.

In August 1942, 13 code talkers were part of the landing that took place at Guadalcanal. The code worked. More code talkers were recruited, and the Navajo code became the official code for the rest of the war, MacDonald said.

The Navajo code talkers performed their mission with skill, speed and accuracy, he said.

He noted that Maj. Howard Connor, 5th Marine Division signal officer, had six code talkers working continuously throughout the first two days of the Battle of Iwo Jima. They sent more than 800 messages, all without error.

Connor later said, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”

MacDonald finished his tour with the Marines in North China and would have a plethora of accomplishments in civilian life including being awarded the Congressional Silver Medal and earning an engineering degree from the University of Oklahoma. He also served as the Chairman of the Navajo Nation Council from 1970 to 1989.

In all, he summed up the legacy the code talkers have in history.

“The Navajo code is a unique World War II legacy. It was used in all Pacific battles to transmit top secret and confidential messages. The Navajo code, commissioned by the United States Marines Corps, saved hundreds of thousands of lives and helped to shorten the war in the Pacific. It is the only military code in modern history, never broken by the enemy.”