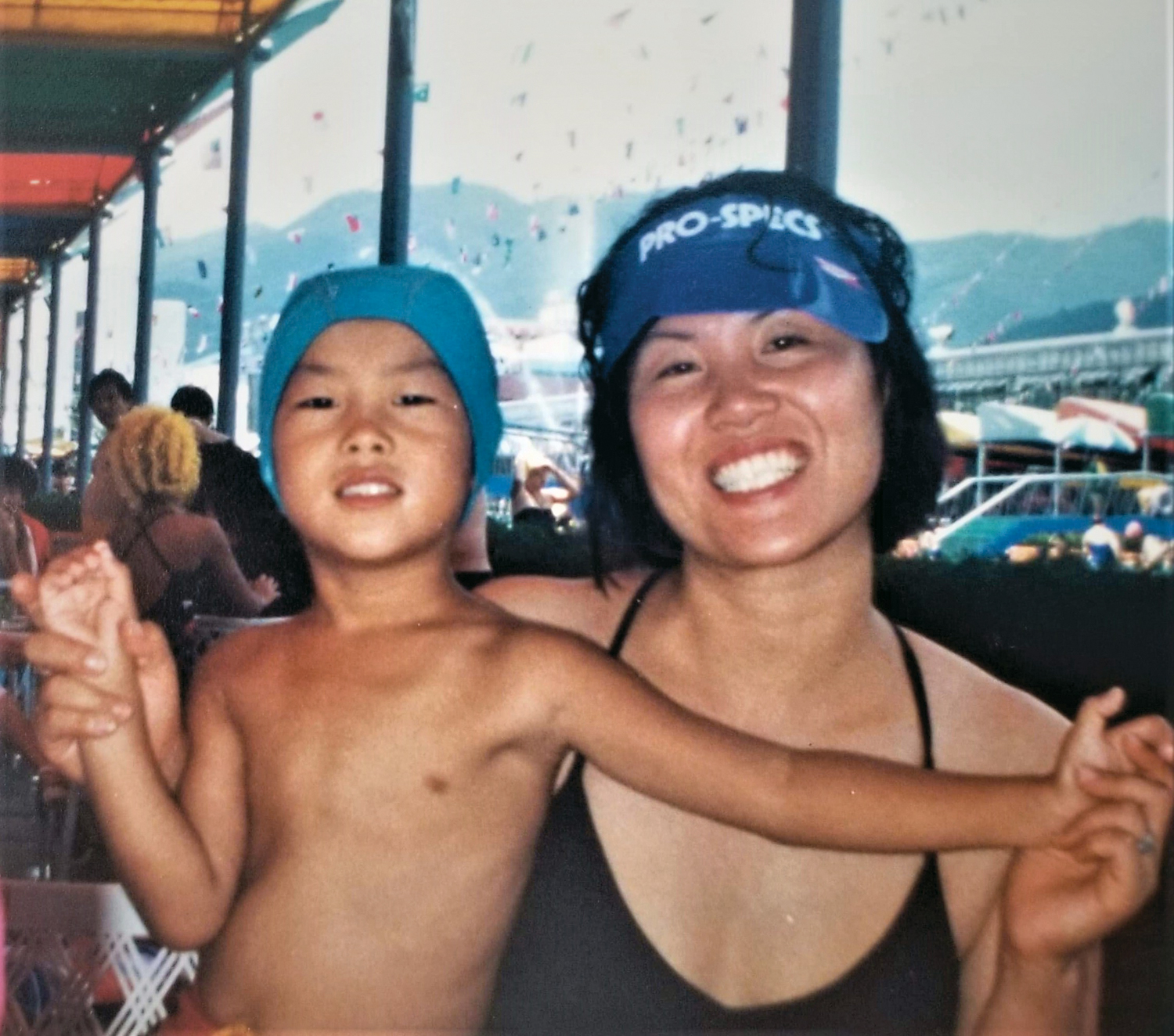

JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-RANDOLPH, Texas – When Jay Park was 8 years old, his parents immigrated from South Korea to the United States in hopes of building a better life for Jay and his older brother. His parents didn’t know it at the time, but, for Jay, that better life would mean serving in the Air Force.

“Most Asian families push the standard, typical white-collar careers — doctors, lawyers, dentists, etc.,” said now-Maj. Jay Park, director of operations for Air Force Recruiting Service’s Detachment 1. “It was always understood in my family that I had to make something of myself, which meant I should pursue one of those standard, white-collar jobs.”

Park instead found his future in a blue-collar job … Air Force blue, that is.

“Even though my parents were both college graduates and had good paying jobs, the chances for my brother and me to do well in Korea were low for many reasons,” he said. “Looking back on the decision to immigrate, I realize how difficult it must have been for my parents to leave everything — family, friends, jobs and community — and move to a foreign country where they had no job lined up and didn’t speak any English. They sacrificed everything just to have an opportunity to make my life better. At the time, I was too young to fully grasp the sacrifices they made. I was just happy to get on an airplane and move to America.”

The Parks settled in Oklahoma, just a few miles from Tinker Air Force Base. And while the young Park constantly saw airplanes flying over his city, he could never picture himself piloting one of the mighty jets that roared overhead.

“I went to a few airshows at Tinker, but it never really dawned on me that I could be one of the pilots,” he said. “Did I want to? Probably. But, internally, it seemed too far of a stretch for me. No one ever said to me directly that I couldn’t be one, but I also never heard someone tell me I could be one, nor did I ever see anyone like me flying one of those awesome jets.”

While Park said he was glad his family decided to make the move to the United States, life was not all roses for young Jay, his brothers or his parents.

“I grew up in a broken home,” he said. “My father was bi-polar, schizophrenic and physically abusive toward my mother. She worked two jobs. During the day, she worked at a salon and during the evenings our whole family would clean office buildings from 5 to 10 p.m. She did it all with many nights of tears and many nights fearing for her life. I wanted to help her, but I also wanted to run away.”

He said, deep down, he knew the best way he could help his mom was to stay out of trouble.

“After all she had sacrificed, I did not and could not burden her more with my selfishness,” he said. “She was also very religious and so strong in her faith. It led me to see the strength she found in God and it helped me find my faith in God as well.”

After graduating high school, Park almost enlisted in the Army.

“I wanted desperately to help my mom so I thought the best thing I could do was to become self-sufficient,” he said. “Thankfully, my best friend’s father convinced me to go to college and join the military as an officer. I had no idea what that meant, but, somehow, I found ways to get grants to help pay for in-state tuition, which allowed me to put the military on hold.”

Even though his tuition was covered, Park found out during his freshman year of college that he still needed an income to cover living expenses. He worked part-time jobs, but soon realized he would need more money if he was to stay focused on finishing college.

“I started looking into ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps) scholarships because I became friends with some of the Air Force ROTC cadets in my intro to engineering class,” he said. “One of them became a close friend of mine who helped me get in touch with the detachments on campus. By the grace of God, I ended up with AFROTC Det. 675.”

After college, Park said his plan was to do four years in the Air Force, thank the military for helping him pay for his education and giving him a job, and then quickly transition to life in the civilian sector.

“What I failed to realize was that the Air Force began to shape me and mold me into a leader,” he said. “It taught me many lessons and allowed me to experience so many wonderful things. It forced me to become more responsible, taught me to manage tasks well, but also to be a leader among my peers. It also didn’t hurt that the ladies in my life loved the uniform.”

It was at this time that Park said he started thinking about becoming an aviator.

“I still remember to this day sitting inside the big auditorium, sweaty and hot at field training in the middle of the Texas summer heat, watching a clip of a B-1B Weapon Systems Officer talking about how cool his job was and thinking, ‘I want to do that!’” Park said.

He set his sights on becoming an Air Force WSO.

“Training to become an F-15 Strike Eagle WSO was long and challenging to say the least,” he said. “But, it was definitely rewarding and the sense of accomplishment was amazing. I would be lying if I told you there weren’t times when I wished I had gone an easier route — same rank, same basic pay, regardless of your job in the military. But, in the end, it was being part of a community, belonging to a group of highly skilled fighter pilots and leaders that drew me in.”

While Park was definitely in the minority as an Asian aviator, he said he never had any issues related to his background.

“Discrimination exists in some form or fashion, no matter where you go,” he said. “But, I never once felt or experienced outright discrimination based on my Asian heritage. The discrimination you felt in the squadron was mostly based on your performance in the jet and your commitment to the organization and fellow aviators.”

Park said he struggled to fit in mostly because he did not understand the dynamics of the squadron, which felt and functioned like a fraternity.

“You have to earn your way in — nothing is given,” he said. “I didn’t understand the importance of camaraderie and teamwork. I thought if I just came to work and did my job that was good enough. I got by on that for the first few years but began to realize I was falling behind.”

He also began to notice the culture here in America was vastly different from what he had internalized as a Korean American.

“Never in a setting of Koreans would someone younger talk directly to an elder and give him feedback,” Park said. “I was shocked at how young captains would talk to majors or even lieutenant colonels during briefs and debriefs. So from the beginning, I went into the squadron with the wrong mentality. I was humble and ready to learn, but maybe too humble. I did not know how to speak my mind. I didn’t know how to fight for myself and just did whatever they asked me to do. I was passive.”

The major said he eventually learned how to better integrate within a squadron and speak up for himself. More importantly, he hopes his successful Air Force career will encourage more Asians to consider a career in military aviation.