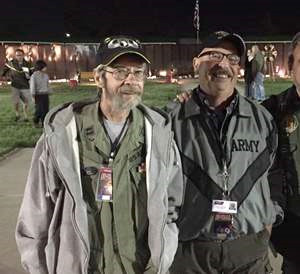

Bob Evans, Army Capt., 101st Airborne Div., Vietnam Class of 1969 with fmr Sgt. Anderson at the Antelope Valley Mobile Vietnam Memorial, Veterans Day observances, 2016. Photo contributed

We lost Bob Evans last week.

A friend said he went quickly, and that it was not unexpected. Also, “He had been working on it for a while.”

The world’s most famous Bob Evans is the movie producer who ushered in Paramount Pictures golden age in the 1970s, mid-life to classics like “Chinatown” and “The Godfather.”

The Bob Evans we lost on April 7 was not so famous, but ever so worthy of remembering.

In the 1970s, Bob Evans of the Antelope Valley was recovering from combat wounds sustained as a platoon leader with the 101st Airborne in Vietnam. In the hot fight, he got shot in the face, and there are some other kinds of wounds that never heal.

Maxillofacial reconstruction is, in medical dictionaries, a “rarely used term.” It relates to reconstruction of the jaw and face.

Bob Evans would bear the scars of combat for the rest of his life.

One of Bob’s closest friends was — and is — Gerry Rice, LMFT, another Vietnam combat infantry veteran, with one of the best reputations for giving insight and counsel to veterans recovering from impact of service.

Most often, a key impact of service is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Gerry, plus another of Bob’s friends, Vietnam veteran U.S. Marine George Palermo, avoid use of the “D” part of PTSD whenever they can.

These combat veterans contend that to cope with post traumatic stress is not a disorder. As Gerry and George put it, it is “a normal person’s response to abnormal experience.”

And that is combat. It may not be abnormal experience in the history of mankind, but the things that happen in combat are certainly abnormal.

What happens in combat, the severe effects, lodge in a part of our brain that is called “the old brain,” or sometimes, “the lizard brain.” It is that part that governs our ‘flight, fight or freeze’ response. It’s the part that stores abnormal experience long term.

I knew Bob and was happy to be a friend of his for about a dozen years.

I recall Bob telling about his return to the United States. He was on a stretcher that was hefted into a bus headed to a military hospital in Oakland, Calif. The bus was traveling over the Bay Bridge, and Bob was watching the other cars in traffic.

“I saw a woman in a station wagon,” Bob recalled. “She was a mother, with kids in the back, and groceries, and she was smiling. And I wondered, ‘How can she be smiling like that?’ And I thought, ‘That looks so normal. How can she look so normal?'”

Returning “back to the world,” there was little that seemed normal to Bob. His was the abnormal return of a severely wounded warrior.

In remembering Bob, Gerry Rice said he heard that Bob had sustained nine years of reconstructive surgery to his face. I do not know if it was an AK-47 round, a ricochet or shrapnel, but I do know it was apparent that while Bob was a pleasant looking man, small — a few inches above 5 feet — and slight, with a leprechaunish grin.

Beneath his wisp of beard it was evident that a large part of his jaw was missing.

The first time we met was in 2005, at the Palmdale Playhouse during a theater revival of a play about Vietnam called “A Piece Of My Heart.”

The play focused on the role of women who served in Vietnam, but it was a drama of consuming interest to women — and men — and anyone who cared about, or was interested in what happened in Vietnam.

For his service in Vietnam, Bob Evans was awarded the Bronze Star with “V” for Valor, and the Purple Heart. What that means is that Bob was wounded, and that he was in the business of doing something that required valor before he was medevaced off the field of battle.

At that time of “A Piece Of My Heart,” I was recently returned from a reporting trip to Iraq in 2004, and my son was home on leave from active service in the Marines. My son deployed for a combat action in Iraq called “Second Battle of Fallujah,” or Operation Al Fahr (New Dawn).

The play featured a panel of Vietnam combat veterans, and my son, Garrett, also participated. Everyone on the panel shared what they could about combat and its aftermath.

After the play that evening a few of us headed over to a local Denny’s restaurant, Bob Evans with us. We drank coffee late into the night and enjoyed each others company in the fast friendship that knits from the bond of military service.

Friends who knew Bob and cared about him worried about his use of alcohol and his incessant cigarette smoking. These, however, are constant, common, continuous worries about many combat veterans.

With Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, of the more than 2 million troops who have served in the Global War on Terror continuing wars, more than 500,000 report some kind of mental distress, ranging from mild to severe.

Of our entire community of veterans, Post 9/11, Vietnam, Korea, all wars and services, the VA estimates that 20 a day choose to end their lives by suicide. Co-morbidity, the mixing of drugs, alcohol and depression, can lead to a kind of slow suicide by substance abuse.

In sociable company, Bob was a cheerful guy, and could be wickedly funny. He also had been an extremely capable and effective guy at different points in his several lives and careers.

Gerry Rice recalled that Bob volunteered to serve his country, “and that his scores were off the map.” Accepted for Officers Candidate School, Bob Evans was among those multitudes of young men who chose to lead, rather than follow. And he stayed in the fight until he was blown out of it and on his way home to a military hospital in Oakland.

After the military, Bob graduated from University of Southern California, and he went on to a career in the federal government with the National Transportation Safety Board.

“Child safety seats in cars,” Gerry Rice said. “He had his process, and his fingerprints all over those. You can imagine that the work he did saved a lot of young children’s lives.”

Bob Evans was also present at the dedication of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 13, 1982. Both of us were there, although we would not have known each other. Among the thousands of Vietnam War veterans, clothed in boonie jackets and hats, and sometimes coats and ties, I was on scene to cover the event for United Press International. Some 35 years later, I am amazed that I was there for a momentous benchmark in the history of the ragged and often times anguished life journeys of the veterans of Vietnam.

“Bob was there, in suit and tie, escorting people to the memorial,” Gerry Rice said.

It was about 30 years later that Rice and Evans became acquainted, appropriately at a presentation in Lancaster City Park of one of the traveling Vietnam Memorials — called “The Traveling Wall.”

“It was really when I was just ‘coming out’ as a Vietnam veteran,” Rice said.

Rice, like so many from his time in service, spent decades “stuffing the memories,” and looking away from his emotions about one of life’s most emotionally charged events, Odysseus returning from war.

That interlude at a traveling Vietnam Memorial in Lancaster City Park (now Steve Owens Park) spurred on Vietnam veterans like Rice, and Evans, George Palermo and Mike Bertell, to seek allies and friends who would help them build the Antelope Valley Mobile Vietnam Memorial.

The friends who joined forces to make that happen, many of them part of the talking recovery group Point Man of the Antelope Valley, managed with the help of literally thousands of donors, to construct a lasting legacy, the AV Wall. The AV Wall remains one of the few grass-roots, community-driven efforts to have a legacy monument to the sacrifices made by the troops who served, and by those more than 58,000 who never returned to their homes.

At some point, Bob retired from the federal service. And at some point, it seemed as if he was taking retirement from life. And then, well short of his 70th birthday, he took leave of life altogether.

What occurs to me is this: the steep price that was paid by the more than 2.5 million Americans who served in the Vietnam War. Many returned to whatever it is that we call “normal” lives and careers. But entirely too many ended up mentally tormented, and self-medicated with drugs, alcohol and tobacco, and entirely too many have ended up homeless on our streets.

After the Army, Bob kept moving forward. He graduated from USC, had a career, and kept his friendships. But like so many others, his was a life that was interrupted, and forever re-directed, because of his decision to serve his country in the most dangerous way possible, as a combat soldier, on the ground, in the fight.

His life ended entirely too early for all who knew him well enough to call him a friend.