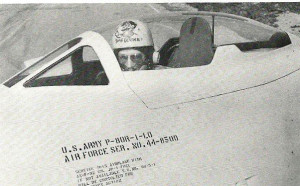

Col. Albert Boyd posing with Racey after the successful attempt to set a new world speed record.

A record in the desert

Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1 always get the gloss when it comes to the record of speed in aviation.

But when you ask people about what was going on before the X-1 ever showed up in the High Desert to keep pushing the envelope as to speed, you just get a blank stare.

Let’s go back in time to November 1923 when two Navy pilots at Mitchel Field in New York were on a mission to become the fastest in the air. Lt. Alford Williams and Lt. Harold Brow took turns taking a Navy Curtiss Racer into the air. After some breathtaking dives and low altitude passes over the field, Al Williams emerged the winner on Nov. 4, with a blistering speed of 266.58 mph.

From that flight it would be nearly a quarter of a century before a United States plane would claim the record of “World’s fastest aircraft.” In the interim, the British owned the skies with the fastest aircraft and kept raising the bar, while the American aircraft industry was always playing catch-up.

When a British Gloster Meteor MK4 established the record flight speed of 606.25 mph on Nov. 11, 1945, Gen. Hap Arnold had seen enough and issued an order for an assault on the world speed record.

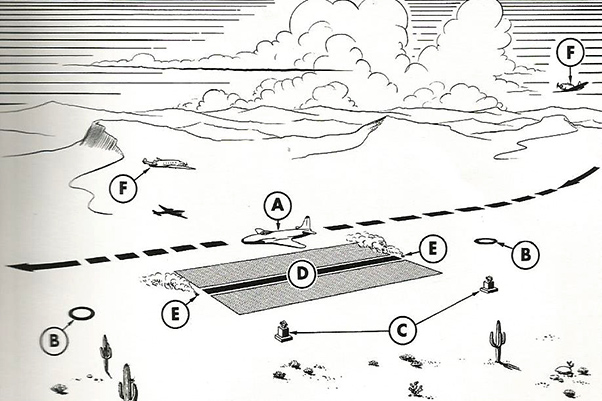

The speed course set up on the dry lake bed at Muroc for the record attempts.

American pride was taking a beating.

Aircraft in the U.S. inventory of the jet variety were not very promising at the end of World War II — except for one. A Lockheed P-80A undergoing flight testing at that time indicated that, in its stock configuration, it “could” attain the speed of 615 mph.

Kelly Johnson and his team were up for the challenge, but the speed of 615mph was too close to the top speed of the British Meteor. Johnson’s team did not want to risk the Brits re-capturing the record from the Americans, so a target speed of more than 635 mph was set as the benchmark.

In 1946, Muroc Field became a beehive of activity in the High Desert, as the high-speed trials of a stock P-80A were being conducted by Lockheed test pilot Maj. Kenneth Chilstrom and engineer Lt. H.D. Wright.

After many flights, they were disappointed to find that a stock airframe could not break the 600 mph barrier. So at that point the stage was set for the birth of “Racey,” a modified P-80A that had a $75,000 equipment upgrade that included flush-type air entrance ducts, a new leading edge for the wing, square wing tips and water-alcohol injection for the newer, bigger Model 400 J33-23 engine.

An abbreviated windshield and canopy, covered gun ports and a gleaming gray glass-like finish left what was now called the P-80R ready to go, after months of disappointing test results and setbacks.

One of the four passes caught on film as Col. Albert Boyd pushed the performance of the P-80R to a world record.

The three-kilometer speed course was set up at Muroc (now Edwards) and, adhering to a very strict book of rules for speed records, the day finally came. Col. Albert Boyd would be the man to try to set the record.

The combination was right. Boyd and Racey were an unrecognizable blur as they swept down the wide black strip in the vast parched silt of the dry lake bed. Using the same procedures and course established by Chilstrom in the 1946 high speed tests, and guided by pink smoke flares set off at both ends of the course for each pass, Boyd flew four separate runs at speeds of 617.1, 614.7, 632.5 and 615.8 mph. The average speed of 623.8 mph exceeded the existing mark of 615.78 mph achieved by the British in September 1946.

From Al Williams and his Navy Curtiss Racer to “Al” Boyd and Racey, it had been 24 long, frustrating years. But at last the United States — thanks to the dedication and ability of the test teams and the work force of the Antelope Valley and Burbank — once again gave the title of “the official holder of the world’s absolute speed record” back to the people of America. From that point it was play catch-up by the rest of the world.

Famed Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier also played a big part in the development of Racey here showing the reduced windscreen and canopy design to cut down on drag. Tony’s unique helmet speaks to a different era of flight test!

The X-1 would take to the skies soon after for a new record of sorts, as the sound barrier was broken and the leapfrogging of speed was a constant in the skies over the Antelope Valley.

For a short time, the Lockheed P-80 named Racey and a pilot named Al became the subjects that would find a place of honor on bubble gum cards along with the heroes of sports, because the title was brought home and it would inspire the young men and women that dreamed of such things in their own lives.

Until next time, Bob Out …