By Bob Alvis, special to Aerotech News

Dr. Wernher von Braun and his supersonic A-4/V-2

Looking back at the breaking of the sound barrier in 1947, it’s interesting to recall all the stories and tales that surround that one special October day at Muroc/Edwards.

When you take into consideration all the technology available before that time — especially the progress made in aircraft and weapon systems during World War II — it puts the push to break that invisible barrier into context.

Engineers realized that it was not an impenetrable wall. In fact, man-made devices were traveling that speed on a regular basis as far back as 1943 with no real structural damage. The only difference was that there was no man on board. The engineers of the day could really care less about that aspect of going supersonic, as there was a war going on and they were just trying to build weapons and along the way prove some scientific theories when it came to flight.

During World War II, the Germans were making incredible advances in flight technology. Dr. Wernher von Braun was at the forefront of those efforts. One day he would lead a group of scientists who would help the U.S. make it to the moon — but during World War II, he was working for his homeland. Germany’s developments in rocketry under the constant pressures of war were nothing less than amazing, always testing the doctor and his rocket team.

Chuck Yeager and the supersonic X-1.

On his fourth flight attempt on Oct. 3, 1943 the sound of a manmade sonic boom from a manmade craft was produced for the very first time, when a craft dubbed the A-4 which stood 46-feet tall at the Peenemunde launching pad on the Baltic Sea achieved that milestone event. Twenty-four seconds after liftoff, the craft accelerated past Mach 1, eventually reaching Mach 4 or 5. That’s when the phone rang and an observer some five kilometers away reported the distinct sound of a “Ba-Boom” to the gathered staff at the test bunker.

The European leaders in the world of aeronautical science had been correct: supersonic flight in its early manifestation meant that a shock wave would make a cracking sound just like the one made by an artillery shell going faster than sound.

From Sept. 5, 1944, to March 27, 1945, the basic A-4/V-2 had 3,165 successful operational flights, dumping high explosives on Great Britain and each time passing the Mach 5 speed, while maintaining its structural integrity. The craft was physically larger than an X-1, which was still two years away in development from achieving supersonic flight.

Looking back, it’s noted that the scientists of the day didn’t seem distressed at the idea that their rocket ships would disintegrate as they struck the so-called “sonic wall.” Did NACA and U.S Army Air Corps know of these German rocket exploits and of high Mach speed flights? Of course they did. Even before the end of the war, the crack of sonic booms were heard over the deserts of New Mexico. Captured German V-2s made more than 130 flights from 1946 on, under the watchful eye of NACA, Von Braun and his associates.

In April 1944, Squadron Leader Anthony F. Martindale, put this Mark XI Spitfire into a dive. The reduction gear designed to limit its speed failed. The propeller ripped off and the diving aircraft reached more than 620mph (1,000km/h) — Mach 0.92 — as it plunged towards the ground.

So the hype of the sonic wall was really just theater of the day, used to bring drama and funding to the projects from a war-weary nation and its congressional leaders. I for one am glad those purses did open up and dollars flowed to start the process that would end up giving the United States the greatest Air Force in the world.

One item that I discovered while researching this story that may interest you when it comes to Mach 1 was about piston-driven aircraft. Many stories came out during World War II that various airframes from the Hellcat to the P-47 Thunderbolt — and yes, even the P-38 Lightning — had pilots tell of reaching that magic number in a dive and living to tell about it. The reality is that just could never have happened with the designs of the day. Even the early jet and rocket aircraft of the Luftwaffe could have never reached those numbers, with the design and construction materials being used.

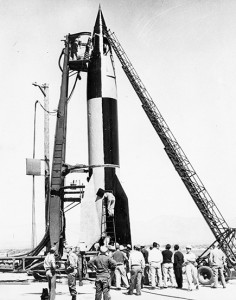

A V-2 at White Sands, N.M., under the watchful eyes of NACA and American aerospace engineers.

So with that being said, what was the fastest recorded speed of a piston-driven aircraft attempting that magic Mach 1 number? Believe it or not, with a demonstrated ceiling of 45,000 feet and a thin elliptical wing and a lower profile liquid-cooled engine, a piston-driven aircraft registered an incredible 0.9 Mach number. That is the highest recorded speed — by a substantial margin — of any propeller driven fighter. The aircraft? It was the British Spitfire. Oh yes, and by the way, when the screaming Spitfire reached the denser air at 20,000 feet the propeller and much of the engine cowling parted company with the airframe — but at least the pilot survived to tell the tale of one heck of a ride!

So there you have it. When Hollywood speaks of the demons out in the thin air remember, just like selling a project with hype for the public, Hollywood does the same to sell tickets! But I know you folks already know that as we all smile and wink!

Until next time … Bob out!