There are individuals who come into other peoples’ lives as if they were designed by God to be there. Often there are circumstances that lead them to be at a certain place and to come into someone’s life at a time of profound need and, in some cases, desperation.

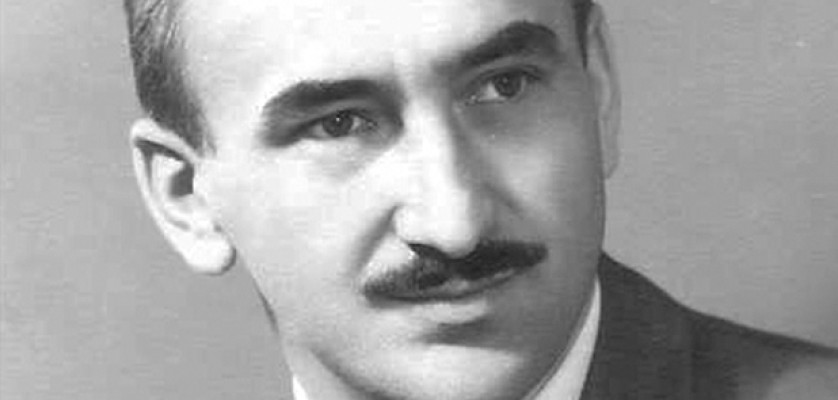

One such person was the late, Dr. Zhigniew ‘Paul’ Dybczak, a native of Poland, who would be recruited to resurrect the failing School of Engineering at the Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, in 1960. The Engineering department had fallen on hard times, having only six faculty members and only one with a master’s degree. The school was hampered by a tiny budget of less than $60,000, inadequate facilities and a student body ill-prepared to graduate as engineers.

George L. Washington, assistant to the president of the university, accomplished a miracle in getting Dr. Dybczak to accept this challenge in building a viable School of Engineering. However, thanks to the powerful legacy of Dr. Booker T. Washington and Dr. George Washington Carver, Dr. Dybczak was inspired to take on this profoundly difficult task, which was made even more difficult by the prevalent bigotry and racism of the white community in Tuskegee.

Dr. Dybczak’s road to Tuskegee University was filled with danger and obstacles that would have defeated a lesser person.

His historic and providential journey to the Tuskegee Institute began Sept. 1, 1939, when he was 15, under horrifying conditions.

Germany invaded Poland with more than 2,700 tanks, 1,400 airplanes and more than 1.5 million troops. The German military broke through the Polish defenses in a rapid fashion and advanced on the capital city of Warsaw in a massive encirclement and defeated the Polish Army within weeks. Tens of thousands of Poles who had fled to eastern Poland were trapped by the Soviet Union’s invasion Sept. 17. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin divided Poland.

More than 1.5 million refugees were deported to forced labor camps in Gulags. Zhigniew and his brother were part of these refugees who worked in the Russian forests as lumberjacks.

However, everything changed when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, June 22, 1941, leading Stalin to become aligned with the British. As a result of his newfound connection with the British, Prime Minister Winston Churchill required Stalin to create an amnesty program which would allow many Polish refugees to be inducted in the British armed forces to fight the Germans. Zhigniew and his brother joined the Polish arm of the British Royal Air Force, where they served until the end of the war.

Dr. Dybczak earned a Mechanical Engineering degree from the University of London in 1950 and worked as an instructor and design engineer before migrating to Toronto. While there, he was a lecturer at the University of Toronto and simultaneously earned his doctorate degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1959.

His Ph.D. opened the door to numerous opportunities. He accepted a position with the Atomic Energy Commission in the United States. Shortly afterward, it was on to his new job at Tuskegee University.

His appointment to his new position was a good fit not only because of his qualifications and education, but because having escaped the tyranny of Hitler and Stalin. Dr. Dybczak had a deep empathy and compassion for oppressed African-American people, particularly in the south. He and his wife had to endure vicious name calling and threats, especially when local whites learned they were living among the African-American faculty at the campus.

Dr. Dybczak wasted no time in rebuilding the electrical and mechanical engineering programs. He had the zeal of a new coach turning a losing program into a winner. It is difficult to have a first-class program without competent and brilliant candidates joining your university, so Dr. Dybczak initiated a vigorous recruitment program for faculty and promoted engineering as a realistic career for minorities and women.

What’s more, within two years, he started a graduate program in electrical and mechanical engineering and eventually nuclear engineering, which would attract senior faculty and graduate research assistants.

The new dean realized the importance of grass-roots participation by encouraging faculty visibility at high school career days, school visitations and involvement in the Southeastern Consortium of Minorities in Engineering.

Dr. Dybczak had personally recruited a diverse faculty of 18 people with a wide range of specialties, experience and nationalities by 1965, and by the 1970s he started a chemical engineering program.

His devotion, brilliance and hard work made the Tuskegee’s College of Engineering and its graduates top competitors in the nation. Enrollment of engineering students increased from approximately 130 to 600 in his final years at Tuskegee.

Dr. Dybczak worked tirelessly to bring Black colleges together and was a founder of the Black Engineering College Development Committee of the American Society of Engineering Education. He stayed the course in his 21 years, despite the obstacles and sacrifices he and his family endured.

Retired Air Force Colonel, Richard Toliver said that he owes a tremendous debt to Dr. Dybczak.

“Although I was deeply committed to graduating in engineering, my academic results were sporadic at best,” Colonel Toliver recalled. “I had demonstrated the ability to do well is some courses or when work and personal distractions were lessened. After a hard scrutiny of the likelihood of being successful and a candid discussion, Dr. Dybczak made a momentous decision that allowed me to continue in school. He wanted me to rededicate myself to going forward with my life.

“I gratefully accepted this unprecedented opportunity and promised Dr. Dybczak he would not be sorry. This man literally saved my life.”

Many graduates owe Dr. Dybczak a tremendous debt. He received numerous awards, citations and letters, including one from former president Bill Clinton. These small mementos cannot begin to appropriately honor this great American and servant of mankind.

Dr. Dybczak died Nov. 22. 2020. Thank God, it is He who will ultimately bestow a just reward upon this incredible, matchless Uncaged Eagle, Colonel Toliver said.

Editor’s note: The author would like to thank retired Air Force colonel, Richard Toliver for his invaluable help in offering his recollections and supplying vital information that made writing and putting this article together possible.