OSHKOSH, Wisc. — Anywhere you travel where the history of aviation looms large, you will fly right into the legacy of aerospace in the Antelope Valley whether it is at the Smithsonian in the nation’s capital, or Oshkosh, Wisc.

Antelope Valley aviation fans or pilots and the ones who love them wing their way to Oshkosh for the Experimental Aircraft Association’s “Fly In,” an annual confab of all things with wings from the world over.

The “Fly In” is usually in July, and my daughter, Grace, who lives nearby tells me that “RVs and tents will be lined up for miles outside the Oshkosh Airport. Then the planes arrive in glints of silver and colorful splashes of paint.

Driving onto the airport and museum access road, we first caught sight of a C-47 “Skytrain” transport of the kind that put 13,000 paratroopers out in the angry skies over Normandy in the opening hours of June 6, 1944.

The EAA’s museum hosts an innovator’s and pioneer’s pantheon. At the EAA Museum during a recent family visit we found a gallery dedicated to the Rutan Brothers, Burt and Dick.

That was after walking past some remarkable replicas, homages to the Wright Flyer, the Spirit of Saint Louis, and a racing plane that Jimmy Doolittle piloted to a world record long before he and his B-25 Mitchell task force spent “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo.”

By itself, the display of all the Rutan-designed aircraft is breathtaking for aviation enthusiasts.

Burt Rutan invented some of the most innovative air and spacecraft of the past half-century, to include the “around the world on a single tank of gas” Voyager, and the incredible SpaceShipOne and Two, which ushered the dawn of private industry space flight. Dick Rutan is the daring Vietnam War combat pilot who flew Voyager, accompanied by Jeana Yeager, no relation to Chuck Yeager.

Within the multiple galleries are racing planes, sea planes, test planes, experimental planes, and above all, historic planes.

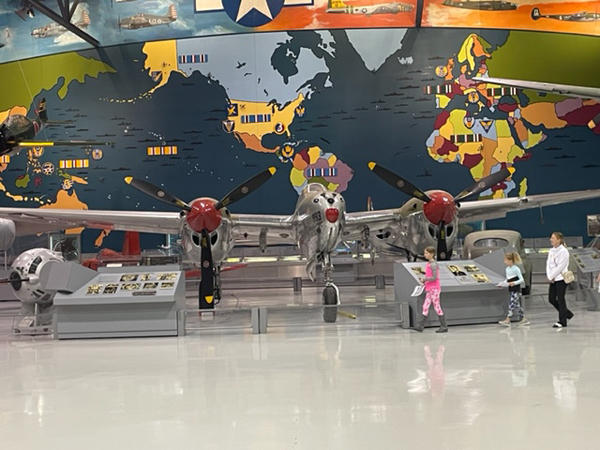

The Eagle Gallery of the museum features famed War Birds of World War II, both in replica and the original. The gallery features two variations of the P-51 Mustang, the best long-range fighter of the war. There is also a Vought Corsair of the Pacific War as well as a Mitsubishi “Zero” fighter of the kind flown by Japan during the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into history’s biggest war. A Messerschmitt Me-109 is suspended high above one of legendary Lockheed designer Kelly Johnson’s earliest masterpieces, the twin-boom supercharged P-38 Lightning.

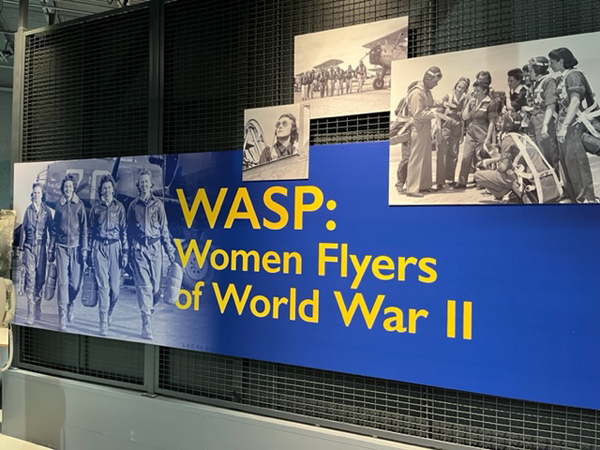

In the Women’s Air Service Pilots gallery, there was a photo of Chuck Yeager, the grinning World War II fighter ace in flight suit, chatting at jet fighter cockpit with Jacqueline Cochran, first woman to break the sound barrier in 1953, a little less than five years after Yeager ushered in the world’s first sonic boom flying the Bell X-1 named for wife Glennis, “Glamorous Glennis.”

What a pair, those two, Yeager and Cochran. They were both comrades and friends. Cochran, a formidable test and racing pilot in her own right, was architect of the Women’s Air Service Pilots, the WASPs of World War II.

In the decades before women would be admitted to the ranks of combat aviation, the 1,000 WASPs overseen by Cochran trailblazed a legacy of flying bombers and fighters. To free men for combat flying, the women ferried aircraft, flew test, and towed targets. They weren’t afforded veteran status until decades after the war they helped to win. Thirty-eight WASP pilots died in the line of duty.

In 2010, about 65 years after the end of World War II, surviving WASPs were honored with the Congressional Gold Medal in Washington D.C., with newsman Tom Brokaw, author of “The Greatest Generation” presiding. Among the pilots honored were three Antelope Valley WASPs, Marguerite “Ty” Killen, Irma “Babe” Story and Florabelle Reece.

To have them among us in 2010 was an honor and human history treasure trove. They have all passed on with the millions of other World War II veterans leaving us nothing but their memories.

Ty Killen, whose nickname “Ty” stood for “Tiny,” described how at the ceremony in the Congressional Gallery, she rushed into Brokaw’s arms, embraced him, “and gave him a kiss, a big one!”

Killen recalled how she met the future Sen. Barry Goldwater twice. Once was during the war when she was refueling the future national candidate’s aircraft. “I’m sure he thought I was a man, a very small one.” The next time was about 20 years later when he was about to receive the Republican nomination for president.

Ty Killen, “Babe Story” and Florabelle Reece made a “farewell tour” visit at the Antelope Valley Fair in the mid-2000s where they were surrounded by young girls and women, seeking autographs from the female aviation pioneers who had dared so much to fly for the United States during history’s biggest war.

And the three women were invaluable, providing living lessons in the classes of retired Lancaster High School teacher Jamie Goodreau, and also accompanying Aerotech News writer and aviation historian Bob Alvis on classroom visits.

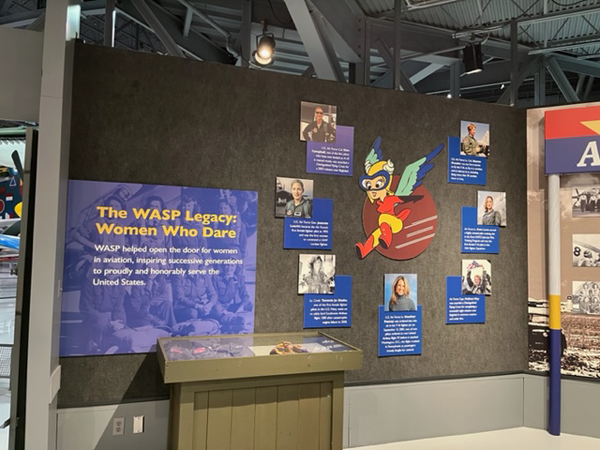

So, the legacy of the WASP program is memorialized in a large gallery at Oshkosh, along with context and the significance of the WASP flyers for the future of women flying in the U.S. military.

You can’t walk a few dozen steps at the Oshkosh museum without sighting history of Yeager, the Mach-busting pilot renowned for breaking the sound barrier first in the skies above Muroc Air Force Base on Oct. 14, 1947.

In 1949 the base would be named after test pilot, Capt. Glen Edwards, who went to glory test-piloting the YB-49 Flying Wing. That legacy gave us Edwards Air Force Base, and the B-2 Stealth bomber.

From the Smithsonian Museum of Air & Space on the Mall in Washington, to the Experimental Aircraft Association Museum in Oshkosh, the legacy of the Antelope Valley in air and space history is writ large.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is author of three published novels of military aviation, “Target Stealth,” “Blackbird,” and “Arthur, King.” An Army paratrooper veteran, he works on veterans’ issues and continues to make military parachute jumps from a D-Day vintage C-47 transport with the non-profit Liberty Jump Team.