Four days after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, America suddenly found itself at war against the combined might of the Axis powers of Germany, Italy and Japan.

Achieving victory would be a massive effort that would require the participation of not only those who were currently serving in the military, but also those civilians living and working at home.

From December 1941 to Japan’s surrender in September 1945, more than 16 million men and women answered the call to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces. Today, because of their sacrifices for the ideals of freedom, they are collectively known as the Greatest Generation.

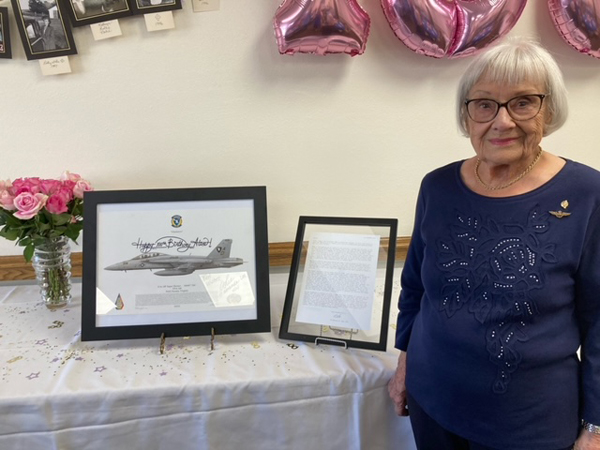

Alice Starnes who celebrated her 100th birthday on Sept. 23, is not only a member of this generation, but is also a trailblazer in her own right: she was one of approximately 100,000 women who volunteered to serve in a special branch of the U.S. Navy Reserve known as the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES).

The WAVES were the first of their kind: up until this point, women had been generally forbidden from uniformed military service and the idea of integrating women had not been popular with lawmakers. However, the Navy needed more men freed for sea duty, so President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the WAVES in July 1942.

Around that time, Starnes, who today lives in Lubbock, Texas, was living a relatively ordinary life working as a schoolteacher. However, after hearing about the WAVES from radio and newspaper advertisements, she felt compelled to act, and enlisted in 1943.

“Everyone wanted to do their part, and so I volunteered,” said Starnes.

She attended boot camp at Hunter College in New York City, which was known as the U.S. Naval Training Center (Women’s Reserve). She said her clearest memory from that time was a weekend visit from Frank Sinatra, who had been supporting the war effort by giving free concerts for service members. After her initial training was over, Starnes said the next step was sorting the women according to their strengths and then giving them their initial assignment.

“We were given a barrage of tests, and they decided I needed to be in the pilot program,” said Starnes.

Though she probably did not know it at the time, the program that Starnes had been selected for would turn out to be crucial to the war effort. She transferred to Naval Air Station Atlanta, where she was schooled in the operation of the Link Trainer. Otherwise known as the “blue box,” the Link Trainer was one of aviation’s first flight simulators and trained pilots how to fly without the use of visual references.

After completing school in Atlanta, Starnes transferred to what was then known as Naval Auxiliary Air Station Corry Field in Pensacola, Fla. There, along with other WAVES, she used her knowledge of the Link Trainer to prepare over 1,000 American and British aviators for deployment overseas.

“We taught the young pilots how to fly by instruments only,” said Starnes. “They had to learn how to fly at night. They couldn’t very well fly over Germany and not know their instruments.”

By 1945, Starnes had transferred once again to Naval Outlying Landing Field Barin in Foley, Ala., where she continued her work with the naval aviation community. When the war ended, Starnes said she traveled to New York City and participated in the joyful victory celebrations there.

“We marched down 5th Avenue for miles and miles,” said Starnes. “We were so exhausted by the time the parade ended, we didn’t even go on liberty. We went back to the dormitory.”

After more than two years, Starnes left the WAVES with the rank of Specialist Teacher 2nd Class and returned to her former life. Though her own service was over, Starnes’ life since World War II has stayed closely entwined with the Navy. She went on to marry a Navy chaplain and has a son and granddaughter who are both Navy veterans.

“We are a Navy family,” said Starnes.

Adm. Lisa M. Franchetti, U.S. Navy Vice Chief of Naval Operations, recognized Starnes for her service by sending her a letter on her 100th birthday in which she writes, “Thank you for setting our Navy on a course that enabled women like me to lead at the highest levels of our Navy! I am so grateful for your service.”

Alice said that her years in the Navy were so meaningful to her and receiving Franchetti’s letter was such a wonderful feeling.

When thinking back on her service, Starnes always keeps in mind that she was a small part of a much bigger picture. She was not the only member of her family to aid the war effort: her younger brother served in the Navy and her sister worked in a factory producing war supplies in Los Angeles. Although she is proud of her service, Starnes said that, like so many other members of America’s Greatest Generation, she had simply answered the call of history.

“I was doing my duty for my country, which a lot of other people were also doing,” said Starnes. “The people in the United States were so wonderful. I can’t even say how we did it.”