Army Sgt. Maj. Jon Robert Cavaiani fought an overwhelming North Vietnamese force until he couldn’t fight anymore. His actions saved dozens of men who served under him, but they also earned him two years at a prisoner of war camp. When he finally returned home, the Special Forces legend was greeted with respect and, soon after, the Medal of Honor.

Cavaiani was born Jon Lemmons in Royston, England, to an American soldier named Pete Lemmons and a British mother, Dorothy. He had a younger brother named Carl.

When Jon was 4, he and his brother were sent to live with their uncle in California. Eventually, his parents came over, too, but they divorced. His mother remarried a man named Ugo Cavaiani in 1950, and they settled in the small community of Ballico, Calif. When his stepfather adopted him in the early 1960s, Jon decided to take the name Cavaiani.

According to the National Museum of the U.S. Army, a young Cavaiani toiled on his family’s farm before working for a fertilizer company and gaining extensive knowledge about agriculture.

In 1964, he married a woman named Marianne. They had two daughters, but they divorced around the time Cavaiani became a naturalized citizen in 1968.

By then, Cavaiani had the itch to join the military because he said he had a few half-brothers who were already serving in Vietnam. He tried in 1969 to join the Army but was deemed unfit because he had a severe allergy to bee stings. He said he eventually persuaded an Army doctor to fill out paperwork allowing him to enlist.

Joining the fight

Cavaiani started boot camp at age 26 and quickly volunteered to join the Special Forces, training as a medic. He was sent to Vietnam in 1970 with Task Force 1, Vietnam Training Advisory Group, which later became known as the Military Advisory Command-Vietnam Studies and Observations Group, an elite reconnaissance unit.

When Cavaiani arrived in the country, he was first assigned as an agriculture adviser and veterinarian because of his background. However, he wanted to do more, so he switched to reconnaissance for a few months before volunteering to become a platoon leader. His unit’s mission was to provide security for an isolated radio relay site called Hickory Hill, north of Khe Sanh Combat Base, which was located within enemy territory near the edge of the Demilitarized Zone. There weren’t many men left to defend the hill when Cavaiani arrived – roughly about a dozen American Special Forces advisors and about 70 indigenous soldiers known as Montagnards, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Army.

“When I got up there, the camp was a disaster area. It was just waiting to be knocked over,” Cavaiani said in a 2002 Library of Congress interview. He had it fixed up just as they started to see more activity from North Vietnamese in the area.

Overwhelmed

Cavaiani said he’d only been at Hickory Hill for about a month when the actions that defined his career took place. On the morning of June 4, 1971, the young staff sergeant woke up to find the entire camp under fire from a large enemy force. Without regard for his own safety, he put himself in harm’s way several times to move around the camp’s perimeter to rally and direct the platoon’s return fire using any weapon he could find to join them.

Eventually, it became clear they couldn’t keep up the fight, so they were ordered to evacuate. Cavaiani and another Special Forces soldier, Sgt. John R. Jones, helped evacuate the men into helicopters. Most of the platoon were able to make it out, but Cavaiani said he and Jones stayed behind to destroy the site’s sensitive equipment so it wouldn’t fall into enemy hands.

The pair was forced to stay overnight at the site with a handful of Montagnard soldiers who remained. They strengthened their defenses as best they could before the enemy launched another major ground attack in the morning. Cavaiani returned a heavy barrage of small-arms and grenade fire but was unable to slow the enemy down. He ordered the remaining men to escape, then grabbed a machine gun, stood on top of the bunker that was covering him and swept machine gun fire across the enemy soldiers headed their way.

“I started shooting at anybody trying to come in. Mostly, shooting at where I was seeing flashes, which meant somebody was shooting at me,” he said.

Trapped

Cavaiani was hit several times while on the bunker, but thanks to his bravery, the other men — with the exception of Jones — were able to escape. The staff sergeant said he then tried to grab Jones out of the bunker, but the enemy had overrun the top of the hill by then, and he and Jones were trapped inside.

Cavaiani said they were able to take out two enemy soldiers who came into the bunker, but not before more North Vietnamese were alerted to their presence. Another enemy soldier threw a grenade inside the bunker, which seriously injured Jones.

“[Jones said] ‘I’m going to surrender.’ He walks out, unfortunately. He cursed to them in Vietnamese, and they shot him and killed him,” Cavaiani remembered. “Next thing I know, a grenade came rolling in. It was one of ours, and I kicked it up against the radio, and I guess I yelled ‘grenade.’ And it went off … It took out my radio, so that was the last time anybody heard from me.”

Cavaiani said he played dead when another enemy soldier came into the bunker to see if there were survivors. That soldier didn’t notice he was alive, but when he left, he set the bunker on fire. Cavaiani had to get out quickly.

“I managed to make it to the door. I’ve got burning tar going down my face and my arms and my back. I get outside, and my machine gun [somehow] goes off and shoots me — the only time in the entire war I wore a steel helmet. It shot me right in the head,” Cavaiani recalled.

He said the shot knocked him out. When he eventually came to, he crawled into another bunker and tried to hide under a bed. He said he passed out there but woke up to an enemy soldier playing with his boot – likely planning to steal it off what he presumed was a dead man – before the soldier got up and walked out.

“That sobered me up real fast,” Cavaiani said. “I did a nice, neat little low crawl over to the door and out the side and over the berm and started escaping and evading.”

Capture

Cavaiani spent about 11 days hiding in the jungle and made it to Firebase Fuller about 42 kilometers away. He said he had no weapons and was badly wounded with about 100 shrapnel wounds and bullet holes. He didn’t realize the area was surrounded by North Vietnamese, who quickly captured him.

Cavaiani spent nearly two years as a prisoner of war before being repatriated to the U.S. in 1973 during Operation Homecoming.

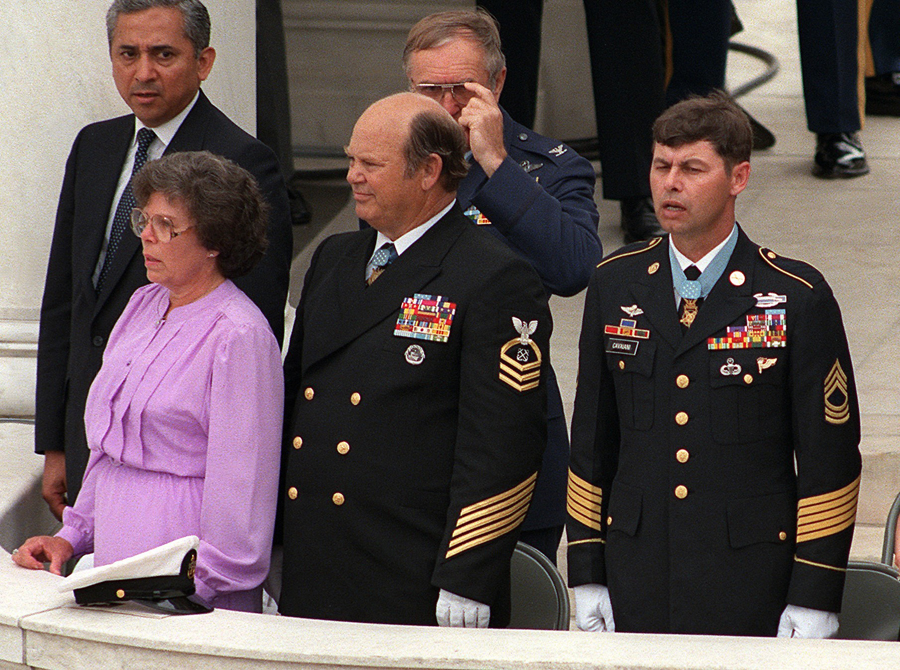

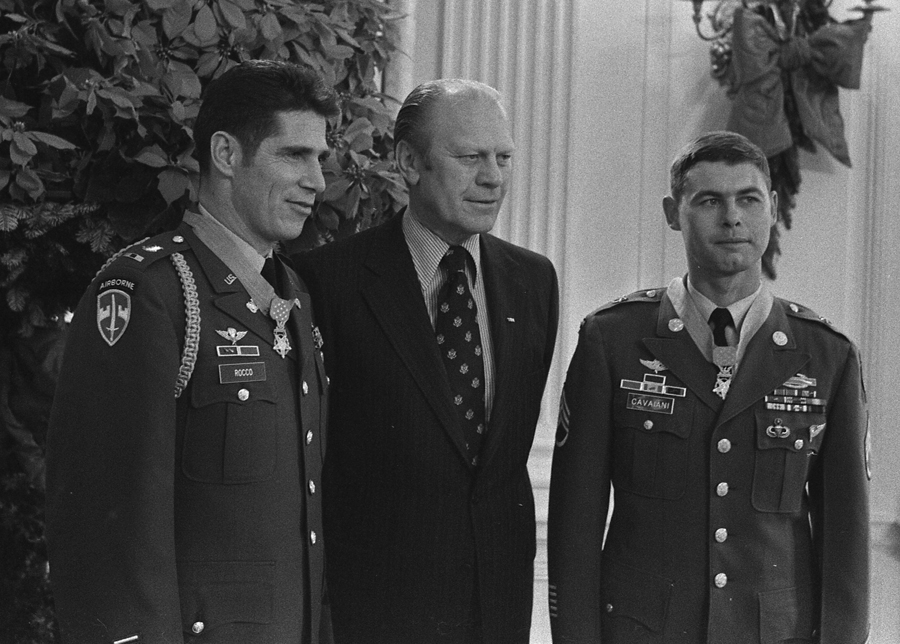

Cavaiani was believed to have been killed in action when he was recommended for the Medal of Honor. Officials learned later that he was still alive. The 31-year-old staff sergeant received the nation’s highest medal for valor from President Gerald R. Ford during a White House ceremony on Dec. 12, 1974. Army Chief Warrant Officer Two Louis R. Rocco also received the Medal of Honor that day for actions he took in Vietnam in 1970.

Cavaiani said he debated leaving the military after he recovered, but he decided to stay in the Army. He eventually ended up in Delta Force, serving in Berlin and working in counterterrorism before he retired as a sergeant major in May 1990.

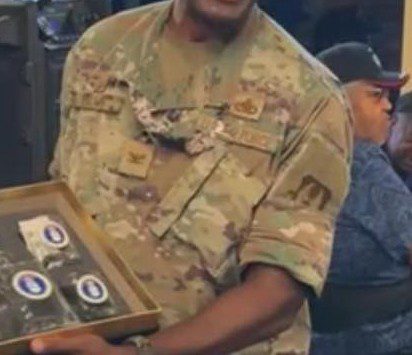

Retired Army Sgt. Maj. Jon Cavaiani hands out candy to children who were descendants of Montagnard soldiers that he led in Vietnam. A team from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command – now known as the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency — deployed to the country for 35 days in 2011 in an effort to locate the remains of individuals lost during the Vietnam conflict.

After

Once again a civilian, Cavaiani went to culinary school and married his wife, Barbara, in 1992. They lived outside of Modesto, Calif., for several years before moving to Columbia, Calif., in 2001.

As for the Medal of Honor, Cavaiani was apparently not fond of being in such an elite club, saying in 2002, “I spent a long time trying to forget about Vietnam. Then you get the medal, and now all of a sudden, it’s public knowledge.”

However, he carried the responsibility with grace, traveling the country as a motivational speaker and to appear at veterans’ events, as well as to teach children about Vietnam War history. He also served as a regional director of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society for a time. In 2011, he was inducted into the Special Forces Hall of Fame.

That same year – 40 years after the battle he would never forget — Cavaiani returned to Vietnam. This time, it was in search of the remains of Sgt. Jones, who was there with him during the ordeal but didn’t survive. Until that point, Jones’ body had not been recovered. This time, however, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting agency found his remains and brought them home. Jones was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in 2012 during a ceremony that Cavaiani attended.

Less than two years later, on July 29, 2014, Cavaiani died of a bone marrow disorder at age 70. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, near Jones and other fallen Vietnam veterans.

Editor’s note: Medal of Honor Monday highlights Medal of Honor recipients who have earned the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.