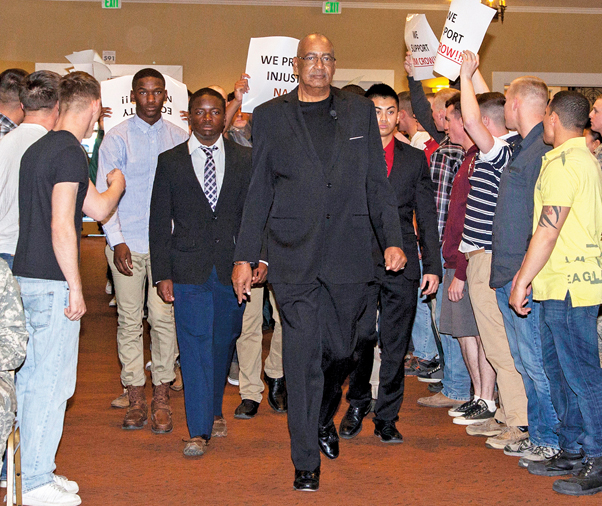

A well-known Department of the Army civilian here, and friend of many, spoke at a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. commemoration, Jan. 7.

John Winkfield, director of the National Training Center Equal Employment Opportunity office, shared a personal story of transformation he attributed to several factors, including seeing Dr. King speak in the 1960’s.

At the ceremony, honoring King and his legacy, Winkfield spoke about his challenges as a young man feeling hate and wanting nothing to do with non-violence his father and grandfather advocated and King practiced during the Civil Rights movement.

“I was centered on hatred, fighting back, hitting back,” Winkfield said. “My father was just the opposite, my grandfather just the opposite. They were talking about the non-violent approach.”

Winkfield grew up in northern California and watched on television the movement during the King era. His parents noticed his anger and took him to a Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“At this conference all my heroes at that time were there – H. Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, Dick Gregory, Muhammad Ali,” Winkfield said. “They all spoke … about fighting back – not being non-violent.

“Finally the last speaker … was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and I never will forget as long as I live … I was 90 feet from him and the podium. There was a time during his speech – and his speech was all about non-violence – [that] he looked down at the audience and to me. I swear he looked right at me. I cannot truly articulate the impact it had on me, on my life. It didn’t happen overnight, but it was a start.”

Winkfield explained that spending nine months in a boys detention camp and being influenced by one of its counselors also made an impression.

After finishing high school, Winkfield enlisted in the Army and as a staff sergeant was tasked to escort a Soldier to her mother’s funeral in Alabama. However, he had vowed to himself never to visit southern states.

“I had sworn that I would never go anywhere south of the Mason-Dixon Line as I grew up,” Winkfield said. “I just refused. I had opportunities to go to a lot of places in the south, but I refused to go because it was passed the Mason-Dixon Line and I was not going to go.”

Once at the Soldier’s home, Winkfield saw the support she received from, not just family, but the community.

“This is when I had to really stop and just pay attention to what was going on, because I saw black people, I saw white people coming in and out of the house and I’m saying ‘wow, ok, ok’,” Winkfield recalled.

Winkfield grudgingly spent the night with a neighbor of the Soldier’s family, who had retrieved his luggage from a hotel and shared meals with him.

“You have to understand my frame of mind, you know, I was messed up with hate,” Winkfield said. “It was destroying me on the inside. I very reluctantly gave in.”

After that moment, Winkfield believes he also gave in to the ideals of King.

“I had to stop … and do what Dr. King said: ‘Let no man pull you low enough to hate him’,” Winkfield told the audience. “I allowed that to happen and as I started to make this transformation from hate to who I am today, John E. Winkfield, I really began to actually live. Before that I don’t think I was really living, I was just existing, not living as a person.”

The Army retiree and NTC veteran of 19 years said it was a challenging conversion.

“It was a tough journey,” Winkfield said. “I had some really rough roads. Each of those rough roads I had to travel was education for me, because I learned a great deal. I learned a lot about myself and people.”

Winkfield came to realize what King taught many during his shortened life: hate will never solve your problems or help you with your problems.

His final quote from King to the audience: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”