The heroes are the ones who didn’t come back from Vietnam.

That’s what a United States Army Veteran told me one afternoon as I listened to him remember his life as it related to the Vietnam War.

He said it was okay to write about our conversation, but to not use his name.

Our talk was brief, but what I learned from hearing and watching him as he spoke gave me a greater appreciation for the man and the situation surrounding not just his experience, but that of others who served and died in Vietnam.

He planned to enlist in 1966 with three friends before finishing high school. They would all get their GEDs in the military. All they needed was parent authorization. His friends got it. His father asked him to get his diploma first.

Perhaps it was a delay tactic.

His father had served in World War II. Other relatives had also served in the “big one” and in the Korean War. These men who had liberated Europe, battled for islands in the Pacific, and fought on the Korean peninsula were by now settled down and raising families.

Our anonymous Veteran told me he and his generation grew up under the mentorship of these Veterans. When Vietnam became the next war, it became their fight. They would not let their fathers down.

But, was it easy for grown men – husbands, fathers, who survived warfare in far-off places – to allow their sons to go to combat knowing it could kill them?

It’s complicated. That’s what I learned.

The draft eventually took our anonymous Veteran to Vietnam in 1968. He and his dad exchanged kisses before he shipped out. After our Veteran returned from Vietnam, his father passed away of natural causes the next day.

His three friends were killed in Vietnam. One before he shipped out himself.

He tried to get streets in the town memorialized with the names of the three. The authorities were not interested. One even told him he didn’t want to hear anything having to do with Vietnam. That described the mood many Veterans encountered upon returning home. The positive, welcome home sentiment was not there.

Mothers in his hometown scanned the casualty lists, which were published every day in the newspapers. The casualty counts were high, the Veteran told me. What did the moms of his friends think of him when he had returned and their sons had not? One mother was especially close to his family. That aspect of the war is a very sad memory, said the Veteran.

He knows where the names of his friends are engraved on the Vietnam War Memorial. He keeps a plaque – a tribute – to his friends, which I believe is his tangible manifestation of their faces, their laughter, and their humanity that is forever imprinted in his mind and heart. Sometimes we need a material item to remind us, and to allow us to hold with our hands something that was good – that’s what I also learned from our anonymous Veteran.

Those are his heroes, the Veteran was telling me.

But they are also the heroes of this nation, from the moment they fell in death. We must not forget them – that’s also what the Veteran was saying.

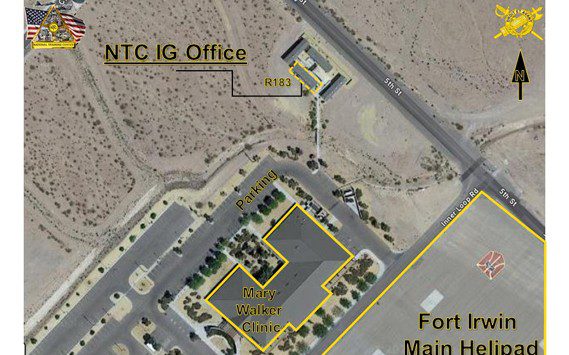

Our anonymous Veteran is very humble and reserved about his service in Vietnam, which included being at Firebase Ripcord. But consider this: he reenlisted and served in the Cold War. Deployed to Granada. Deployed to Panama. Trained at the NTC. He became a “lifer,” as he put it, and served for 26 years.

He was part of the re-building the Army needed after the Vietnam War and then part of a transition that has resulted in the most modern, professional, volunteer fighting force in the world.

Still he doesn’t consider himself a hero. It’s complicated.

So, it’s our job to recognize and appreciate the complexities involved with the Vietnam War and its Veterans – and it requires a personal touch to make it human.

Thank you anonymous Veteran for helping us understand the Vietnam War Veteran.