The US Army’s Fort Irwin, also known as the National Training Center (NTC), occupies 1,000 squares miles of the Mojave Desert in southern California. Its harsh landscape of dry valleys and rocky mountains hosts 50,000 soldiers each year for some of the most realistic military training found anywhere on earth. Along with the realistic training come injury and illness. Protecting the soldiers is a unique medevac unit, C Company of the 2916th Aviation Battalion.

“Our mission is to provide 24-hour aeromedical evacuation support for the NTC and Fort Irwin,” explained Major Matthew Partyka, C Company’s commanding officer. “We do three types of missions here. First, point of injury, where a soldier is ill or injured on the training range and then transported to the nearest appropriate medical facility. If our on-base hospital, Weed Army Hospital, can manage the patient, we bring them back here. If the patient’s condition is beyond what the base hospital can handle, we will fly them to civilian trauma centres. Second, we also do patient transfers from Weed Army Hospital to higher levels of care if any patient’s condition cannot be managed on base.”

The third type of mission, he added, are called Defense Support to Civil Authority (DSCA): “These are off-post mission requests from civilian agencies within San Bernardino County. They most often involve vehicle accidents on remote sections of two major interstate highways in our area. In order for us to respond to one of these requests, we have to be the last resort and the closest resource to the incident. We can also be used if there are no other helicopter assets with our capabilities available such as NVG and/or hoist rescue.”

This is the busiest Army medevac unit in the continental US, flying 132 missions in fiscal year 2015. The most unique aspect of the unit is that a civilian paramedic is part of the crew in addition to the normal Army flight crew of two pilots, a flight medic and a crew chief. The civilian paramedics are part of the civilian base fire department.

The IMMSS litter installation which allows four litter patients to be carried in the helicopter.

“In late 2009, there was a motorcycle accident where no one knew how to call for medical assistance,” stated C Company’s First Sergeant Michael Bishop. “At that time, there was no 911 system on base. Once the base fire department arrived, their level of medical training was only as first responders. When the base ambulance arrived, they did not have a procedure to contact the medevac unit to transport the patient. The patient was transported by ground to Weed Army Medical Center on base. The hospital did not have a rapid procedure in place for serious trauma patients to be transferred to a civilian trauma centre. So, there was no medical system in place on the base.”

Bishop continued: “The base commander put a team together to develop a system of care for anyone on the base and the training ranges. Six paramedics were approved for the base fire department so that two were always on duty. The base commander also approved three additional civilian paramedics for medevac, so one would be on duty with the helicopter at all times. At that time, US Army military flight medics were not full paramedics and were very limited in what kind of care they could provide. The goal was to produce a system that could bypass the local base hospital for seriously injured or ill patients and send them directly to facilities with a higher level of care than could be provided on base.”

The unit has six UH-60A+ helicopters and is authorised to have seven full crews. The unit flew the UH-72 Lakota from 2007 until it transitioned to the UH-60 Black Hawk in 2015. They had to maintain their 24/7 alert posture and train the crews on the UH-60 while maintaining currency and mission capability with the UH-72.

“Our aircraft are UH-60A+ Black Hawks,” stated Partyka. “These have the upgraded T700-GE-701D engines from the L model, but no other changes. They still have the A model transmission, but we get better hot and high performance. We don’t have real high mountains û our tallest is about 5,000 ft [1,500 m], but we often see summer temperatures in the 110 to 115F [43 to 46C] range. These aircraft perform well in these conditions.” Partyka added that the aircraft have Breeze Eastern rescue hoists mounted externally to the cabin. A second modification is the interim medevac medical support system, he explained: “This is a patient litter system that can accommodate four litters and has moveable seats for the crew in the cabin. Another modification is the addition of the FLIR Systems Inc. Talon FLIR system. Because of our mission here and how many times we transport to civilian hospitals, we were able to obtain Cobham Wulfsberg 5000 radios, which allows the crews to communicate with the civilian hospitals as well as civilian first responders.”

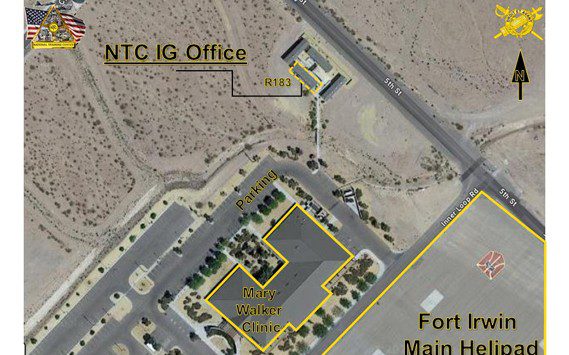

On base, they have a first-up crew, second-up crew, and a spare aircraft. A medevac crew duty cycle is a week, from Wednesday to Wednesday. There are two crews available at all times. Their duty day begins at 16:00 hrs. The crews alternate first-up and second-up duty each day of the cycle. The second-up crew is on a 15-minute call back, i.e. they have to be at the helipad within 15 minutes of being called in. This allows the second-up crew to be with their families on base until needed.

“Each unit that is training in the box [the training range] has observer-controllers (OC) with them that are monitoring and coaching them,” explained Partyka. “When a medevac is needed, the OC notifies range control by radio with the location, number of patients, type of injury, etc. Range control then notifies us over a dedicated phone line that we call the crash phone. We also monitor range control’s frequency, which gives us a heads-up that a mission is being requested. Once we get the call, we contact the 24-hour-alert crew. They come into operations and get the information, check the weather and check the map for the LZ location. We have 15 minutes to be in the air from the time the crash phone rings; we average about eight to 10 minutes to lift-off.”

The first-up aircraft carries a vehicle extrication kit that includes battery-powered hydraulic cutters and spreaders.

The biggest hazard in the box is dust landings, said Partyka: “We always anticipate doing a dust landing whenever we go into the box. We probably do more dust landings than any other unit based in the US.”

The US Army is in the process of upgrading the training of its flight medics to civilian paramedic and critical care paramedic level, known as F2 medics in the Army. Three of the seven C Company flight medics have gone through this training. They use a standard set of protocols developed by the US Army School of Aviation Medicine.

“Combining the two types of medics, military and civilian, created a nice marriage,” commented Bishop. “Each side brings some procedures and medications unique to their world. So, patients get the best of both worlds. For instance, military medics use haemostatic agents that are not allowed by ICEMA [San Bernadino County’s civilian Inland Counties Emergency Medical Agency]. The military medics can also use volume expanders for blood loss such as Hextend. The civilian paramedics bring their expertise to the non-trauma patients. The military medic is great with trauma, but we don’t see a lot of medical patients.”

“Hydraulic rescue tools were something the civilian paramedics brought with them from the fire department,” Bishop explained. “We saw a need for extrication tools based on the mission at the NTC. There are sometimes over 100 vehicles using the training areas during a unit rotation. There is a base crash rescue truck that can respond to off-road incidents, but it can take up to 90 minutes for it to arrive at the more remote training areas.”

“The base authorised funding for dedicated extrication gear for the medevac helicopters. It includes some hand tools as well as battery-powered hydraulic spreaders and cutters. Two sets are kept at the medevac unit at all times. One set is kept on the first-up helicopter at all times. We train twice a year on the equipment and that includes all the military medics, crew chiefs, and pilots. For civilian vehicles, the fire department does the training. For the military vehicles, our military engineers and crash rescue specialists conduct the training.”

The unique location and obvious need for fast, high quality medical care has created a unique system to care for soldiers in this remote part of the US. Bishop said that even when they get all of the military flight medics trained up to the critical care paramedic level, he would not like to see their civilian paramedics go away. He believes they just add too much extra value to lose.