by Dennis Anderson

special to Aerotech News

With Labor Day so close we often brush past dates in August, and this is one that few in the United States paid much attention to, but now that we have already lost most of our World War II veterans, it is a day that should be marked.

Of the 16 million Americans who served, approximately 66,000 are alive, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. They leave this world at the rate of more than 1,000 a week.

On Aug. 14, 1945, Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allies. This happened after the 509th Composite Group of the U.S. Army Air Force dropped two atomic bombs, the first on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, and the second on Nagasaki on Aug. 9.

After a week of argument following the carnage, Japanese leaders who urged surrender prevailed over war party proponents who advocated fighting to the last man, woman and child. Emperor Hirohito broke the tie and directed his people to “endure the unendurable.”

Delivered by the B-29 Superfortress “Enola Gay,” named for the mother of Lt. Col. Paul Tibbets, the command pilot, the A-Bomb christened “Little Boy” killed an estimated 140,000 people by the time of the Sept. 2 Surrender Ceremony in Tokyo Bay aboard the USS Missouri.

World War II’s end was 80 years ago, but its impact reverberates into the present moment.

To prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon, Air Force pilots flying a formation of B-2 Spirit stealth bombers delivered a devastating assault on that nation’s nuclear infrastructure on June 22, 2025, in a mission dubbed Operation Midnight Hammer.

The newest bomber undergoing testing at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., is the B-21 Raider. The Raider is the latest version strategic stealth bomber. It is named to honor the “Doolittle Raiders,” the B-25 bomber crews led by Col. Jimmy Doolittle who made the first attack on mainland Japan just months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The raid was called “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” and it changed the war, and the world to come.

Decades after the war’s end, historian and literature professor Paul Fussell wrote a renowned essay, “Thank God for the Atom Bomb.” Fussell knew war. He was cast into it as an infantry lieutenant and platoon leader who described the carnage vividly in his book “Wartime.”

The astonishing speed and genius harnessed in the Manhattan Project and the B-29 Superfortress program made the bombs that killed 250,000 people at Hiroshima and Nagasaki possible. That annihilation of men, women and children ended the war.

President Harry Truman said his decision was simple, to end the war as quickly as possible.

Whose lives were saved? Among them, multitudes of additional men, women and children Japan’s war leaders would have willingly sacrificed in defense of their home islands.

And in addition, the million Americans whose lives were estimated to be killed in an invasion of Japan.

Here are a few who survived resulting from that fateful decision by Truman. They are men and women who spent post-war years in the Antelope Valley, but they really are from “Anytown U.S.A.,” that iconic community observed in “Best Years of Our Lives,” Best Picture Academy Award of 1946, directed by World War II veteran William Wyler.

Art Wallis and Art Ray were two it was our privilege to have as neighbors in our Antelope Valley. When they left us in recent years, they lived past 90. And what lives they lived.

Art Wallis saw the big flag raised on Mt. Suribachi, the summit on Iwo Jima that inspired World War II’s most iconic American photograph. Associated Press Photographer Joe Rosenthal took the photo used to fashion the Marine Corps Memorial in Washington D.C.

Navy man Art Ray served aboard the USS Quincy, a cruiser that sent rounds flying over the D-Day beaches of Normandy. Less than a year after D-Day, with Art aboard, the Quincy carried President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on his voyage to meet Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Josef Stalin at Yalta to set terms for the post-war world.

Art Ray, with thousands of other sailors, watched from shipboard the day Gen. Douglas MacArthur formally accepted Japan’s surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945.

Ken Creese and Skip Lippert also lived here, as did Remo Cuniberti, and the late Valley Press columnist Bill Gillis, all survivors of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941. Remo Cuniberti survived the sinking of the USS West Virginia. Creese was aboard the cruiser USS Detroit. Skip Lippert manned anti-aircraft with the National Guard at Schofield Barracks. Gillis, Army, went on to Guadalcanal.

The day President Roosevelt declared would “Live in Infamy” was the Sunday morning Japan attacked the U.S. Fleet, killing 2,000 Americans and destroying or damaging a score of ships. The attack plunged America into World War II. The next day would usher in the full force of the American nation. Four days later, Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States.

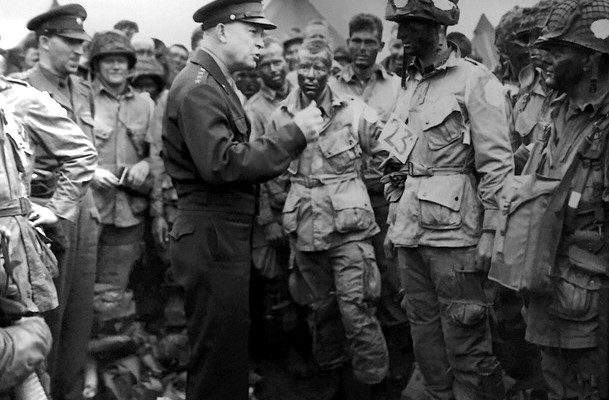

With Hitler dead by suicide and Germany in ruins, the Nazis surrendered May 8, 1945. Some of our neighbors who contributed to that victory included Quartz Hill football coach Lew Shoemaker, a draftee who landed with the Big Red One on Omaha Beach on D-Day.

Shoemaker was terrified. “It may be hard to believe, but if you’re lying face down, there is a certain amount of time you can breathe dirt.” Wounded before the Battle of the Bulge, he survived to meet the love of his life in an Army hospital stateside. They spent their lives together as teachers in California.

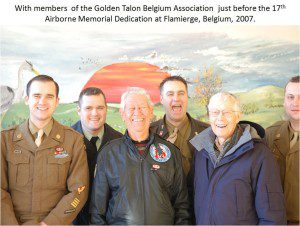

Other D-Day veterans of the Antelope Valley included Henry Ochsner of the 101st Airborne Division, and John Humphrey of the 82nd Airborne, troopers who landed by glider and parachute still busy liberating Europe when the Nazis folded on May 8, 1945. Others who made it home were Adolph Martinez and his best friend Roy Rogel, two paratroopers captured as POWs, who both made their escape from Nazi prison camps.

“Roy said, We better go. I have a bad feeling.” They busted out, made a run for it, and lived. They escaped once from a POW camp, and once from Nazi forces crumbling at war’s end.

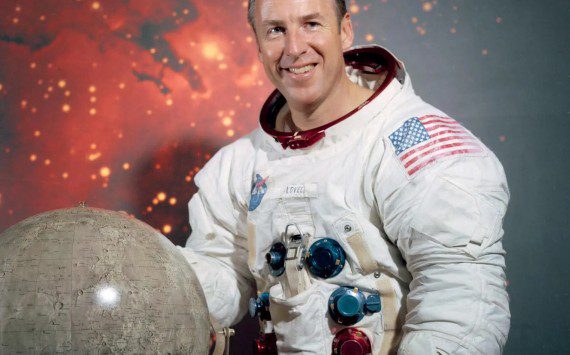

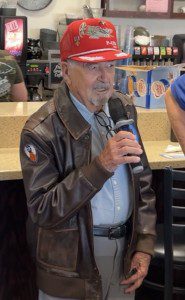

Recently, World War II pilot Ken Placek, who flew P-47 Thunderbolts, visited with Air Force Brig. Gen. Douglas Wickert at Edwards Air Force Base.

The war ended with Japan’s complete surrender Aug. 14, 1945.

A family friend, Marine Palmer Andrews, fought in the last major battle of World War II, the battle for Okinawa in preparation for invasion of the home islands of Japan.

Women risked their lives as combat nurses on invasion beaches, or Women’s Airforce Service Pilots flying missions to free up men for the air war. Ty “Tiny” Killen, Florabelle Reece, Irma “Babe” Story, they also lived here after the war. So did Patricia Murray, who packed parachutes for the Marines, and Lou Moore, who secured D-Day airfields in France. Like the other heroes, they are gone.

It is estimated that 50 million people were killed, including six million Jews of Europe murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust, and up to 27 million Russians in Germany’s war of annihilation.

It is hard for people born in the decades after World War II to grasp how the world would have changed for the worse if the Nazis and Japan had triumphed to usher in what Churchill called “A New Dark Age.”

It is equally hard to grasp that we continue to live under a nuclear sword of Damocles, and how the world would plunge into devastation and ruin if that genie escapes that bottle, sword in hand. It is, in a word, unthinkable.

Albert Einstein said after nuclear war, future battles would be fought with sticks and stones. But the world we live in today, troubled, turbulent but with all its aspirations, better angels, and achievements lives on because a half million mostly young Americans left their mortal lives on invasion beaches, in the sky, and at sea.

Sixteen million served, and for those who returned, their lives were forever changed. They built the country and defended the freedoms we Americans still benefit from today.

Art Wallis and Art Ray? Both were builders who lived adventurous lives, Art Ray skiing and hang gliding. Wallis, a gifted musician, built the Antelope Valley Press plant, homes, buildings. Near end of life, a young social worker asked Wallis his proudest achievement.

He smiled, and answered, “Well, we won the war.”

Eighty years later we need to remember that and give thanks that they did.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is a licensed clinical social worker at High Desert Medical Group. An Army veteran, he is studying for a Masters’ Degree in World War II history administered by Arizona State University and the National WWII Museum.