Visitors to the recent Los Angeles County Air Show at Fox Field in Lancaster, Calif., were treated to a presentation by two test pilots from Virgin Galactic, the privately-funded space company owned by Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and Abu Dhabi’s Aabar Investments PJS.

The Mojave-based project is currently developing a vehicle to take passengers to the edge of space on a ballistic rocket ride ending with a gentle glide to a runway landing.

The commercial space venture kicked off in 2001 when Scaled Composites of Mojave, Calif., began development of the first privately developed manned space vehicle. Designed by Burt Rutan, SpaceShipOne (SS1) was a rocket-powered craft carried aloft beneath a mothership airplane called the White Knight.

Following release at an altitude of 47,000 feet, the SS1 pilot would ignite a hybrid rocket engine fueled by a combination of solid rubber propellant and a liquid oxidizer, and climb above the atmosphere. In 2004, Rutan’s team won the $10 million Ansari X-Prize after SS1 soared above 328,000 feet, the internationally recognized boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space.

Using lessons learned from SS1 test flights, Scaled Composites designed and built SpaceShipTwo (SS2) to carry two pilots and six passengers on brief suborbital flights. A new, larger mothership called White Knight Two was built to carry SS2 to launch altitude and provide pressurization, air conditioning, and electrical power to the spaceship until launch time, about an hour after takeoff.

The first SpaceShipTwo vehicle, VSS Enterprise, climbs during its second powered flight.

According to Virgin Galactic chief pilot David Mackay, the force of the rocket will subject passengers to approximately 3.5g — roughly equivalent to the acceleration of the most powerful drag-race car — for a full minute. “Launch is horizontal, but as soon as the motor begins providing thrust, we pull up into the vertical,” said Mackay. At engine shutdown, SS2 will be moving at more than three times the speed of sound and when the motor shuts off, the spaceship’s occupants will experience weightlessness.

At that point, Mackay said, the passengers will be able to unstrap and float about in zero gravity. To maximize the experience, the cabin was designed with a lot of windows that will provide spectacular views of the curvature of the Earth, the thin blue band of atmosphere, and the blackness of space. Additionally, he said, “The seats will be fully reclined to maximize cabin volume and allow the passengers to do somersaults in zero-g.”

When the spaceship reaches its apogee, at about 328,000 feet, it will start to descend. Passengers will return to their seats, which will remain in the reclined position to absorb re-entry forces up to five times Earth’s gravity. At about 70,000 feet, the vehicle’s configuration changes in a unique way.

When it gets back down to 70,000 feet, the spaceship changes from the feather-shape it has adopted for the drop, back into a glider to make the landing. Unlike previous space vehicles that were made of metal alloys covered with special heat-shielding material, SS2 is built from carbon-fiber composites with virtually no thermal protection. To slow its descent, the crew activates a feathering system that bends the wings and tail booms up into a shuttlecock configuration. “SS2 is the first full-size aircraft to use the feathering system,” Mackay said. “It’s the first vehicle flown that can fold itself in half and then unfold to return to normal flight.”

Mark “Forger” Stucky is the lead test pilot for SpaceShipTwo.

At lower altitudes, the vehicle returns to normal configuration, pitches down into a steep dive, and maneuvers for a glide landing on a conventional runway. In keeping with the concept of a routine commercial operation, the cabin is a fully pressurized “shirtsleeve” environment; neither passengers nor crew require pressure suits at any point from takeoff to landing. Even during the experimental phase of the project, the crew wears only ordinary cloth flight suits. This, according to SS2 lead test pilot Mark “Forger” Stucky, is because the designers have supreme confidence in the vehicle’s structural integrity. “The airframe has been tested to well beyond the load limits we would expect to see during flight,” he said, “there is a great deal of structural redundancy.”

A former military and NASA research pilot, Stucky joined Scaled Composites in 2009 for the White Knight Two and SS2 development programs as an engineering test pilot, technical adviser and design engineer. He flew the majority of SS2’s envelope expansion flights including the first powered flight. He also served as project pilot and instructor during the transition and integration of White Knight Two from Scaled Composites to Virgin Galactic’s commercial operations team, and joined Virgin Galactic as a pilot in February 2015.

Initially, Scaled Composites had full responsibility for the flight-test program. The first SS2 vehicle, dubbed VSS Enterprise, was flown for the first time unpowered in October 2010 by test pilots Pete Siebold and Mike Alsbury. Over the next four years, the team performed more than 50 airborne tests including and 19 captive carry flights, 30 glide flights, and three rocket-powered flights. Mission goals were designed to test the vehicle and its systems incrementally through performance envelope expansion. Although experimental in nature, VSS Enterprise was not considered a developmental prototype. “One of the interesting challenges,” Stucky noted, “was that we have are building a flight-test vehicle that is designed to go into operational service.”

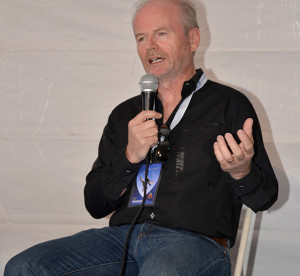

David Mackay is Virgin Galactic’s chief pilot.

The project received its most serious setback in October 2014 when VSS Enterprise, again piloted by Siebold and Alsbury, broke apart at an altitude of around 50,000 feet during the fourth powered flight. When the craft disintegrated, Siebold was thrown clear while still restrained in his seat. Despite being exposed to sudden decompression, extreme g-forces, chilling temperatures and being battered by debris, he somehow released himself from his seat, and his parachute deployed automatically at around 20,000 feet. Alsbury perished and was found in the wreckage. The debris field stretched more than 30 miles from the city of Ridgecrest to the rural community of Cantil. A subsequent investigation revealed that the co-pilot had inadvertently unlocked the feathering mechanism too soon.

Branson vowed to continue the project, with improved safety measures, and responsibility for further testing was given to Virgin Galactic.

A second SS2 vehicle, VSS Unity, became the first such craft built entirely by The Spaceship Company, Virgin Galactic’s manufacturing arm. VSS Unity completed its first flight successful glide test in December 2016, and by early March 2017 four captive-carry and three glide tests had been completed. Stucky noted that the test team was building on the previous work to maximize the value of each test flight. “One of the most unusual things we’re doing this time around is that our test program is not a stair-step kind of thing where we expand the envelope up to the powered flight,” he said. “It’s much more integrated where we may have portions of the flight envelope that we want to prove operationally but we don’t have to do that prior to the initial powered flights.”

Stucky added that he felt very fortunate to be a part of the Virgin Galactic SS2 team. “I used to think I was born a generation too late because I flew for NASA with these great test pilots who had done all this major stuff a generation ago,” he said, “but I don’t feel that way anymore, I feel lucky to be where I am.”

The second SpaceShipTwo, VSS Unity, descends toward Mojave Air and Space Port during a glide test flight.

Although, the Virgin Galactic’s primary goal is to develop a reliable, reusable, and affordable suborbital commercial space tourism system, Stucky admitted that the $200,000 cost for a ticket was not for everyone. “If you look at the price of the ticket, it may be out of reach for most people, but in today’s dollars it’s on par with the initial first class transatlantic tickets back in the 1930s,” he said. “The point is that you have to start somewhere to open it up to the masses and eventually the price will come down through competition.”

To Mackay, who grew up in Scotland during the 1960s and closely followed news of the X-15, Mercury, and Apollo space missions, his job is a dream come true. “I wanted to become an astronaut, so SS2 is a truly fantastic project to be involved in,” he said.