The largest and most complex international construction project in space began on the steppes of Kazakhstan 20 years ago Nov. 20.

Atop its Proton rocket, on Nov. 20, 1998, the Zarya Functional Cargo Block thundered off its launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome into cold wintry skies. Zarya was built by the Khrunichev in Moscow and served as a temporary control module for the nascent ISS.

Nine minutes later, Zarya was in orbit and began unfurling its antennas and solar panels, seemingly coming alive in the airless environment of low Earth orbit. The launch of the first element of the International Space Station kicked off an incredible journey of orbital assembly, operations, and science.

The ISS Program can trace its roots back to 1984, when President Ronald W. Reagan proposed that the United Stated develop an Earth orbiting space station. The United States invited Canada, Japan, and the European Space Agency to join the project in 1988, and five years later President Bill Clinton invited Russia to join the partnership. Russia not only brought its many years of experience with long-duration human space flight to the program but also modules for the planned Mir 2 space station. Former adversaries on Earth were now working together to build the largest laboratory in space.

Left: Zarya as seen from the approaching Space Shuttle Atlantis during the STS-88 mission. Right: Zarya has been mated with Unity in the Shuttle’s cargo bay and astronauts are outside making connections between the two modules.

On Dec. 4, Space Shuttle Endeavour on the STS-88 mission roared off Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, carrying the Unity Node 1 module in its cargo bay. Built by The Boeing Corporation at a facility at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., Unity was the first American component of the ISS. Two days after launch, Endeavour and her six-person crew rendezvoused with Zarya, and using the Shuttle’s robotic arm, captured the Russian module and mated it with Unity. Designed and built by engineers thousands of miles apart and never joined together on Earth, the first two modules of the ISS fit perfectly together when they met in space. The STS-88 crew spent the next few days making connections between the two modules before releasing the newly formed but still embryonic ISS. This marked the first step in the assembly of the ISS, which continued for 13 years.

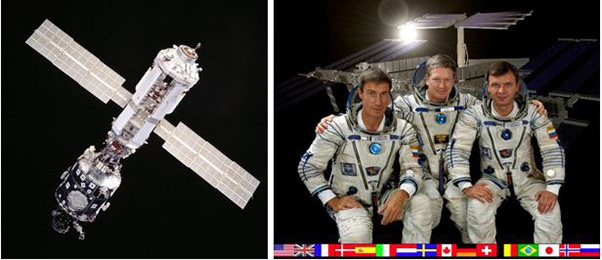

Left: The first two segments of ISS after release from Space Shuttle Atlantis – Unity Node 1 at left and Zarya Functional Cargo Block at right. Assembly of ISS is underway! Right: The first crew to work and live aboard ISS (left to right) Flight Engineer Sergey Krikalev, Commander William Shepard, and Flight Engineer Yuri Gidzenko.

By late 2000, the ISS was ready to receive its first long-duration residents. On Oct. 31, the Expedition 1 crew of William M. Shepard, Sergey K. Krikalev, and Yuri P. Gidzenko blasted off from Baikonur and docked with ISS two days later. Since that day, international teams of astronauts and cosmonauts have kept the ISS permanently occupied, performing the routine operations and maintenance on the station including dozens of spacewalks and conducting research in a wide array of scientific disciplines.

Today, the ISS is the largest space vehicle ever built and a unique laboratory for conducting research in a wide variety of scientific disciplines. Including its solar arrays, it is as large as a football field. The habitable volume in its various international modules is larger than a six-bedroom house. Since November 2000, more than 230 individuals from 18 countries have visited the ISS. As a laboratory, the ISS has hosted more than 2,500 scientific investigations from more than 100 countries.

The International Space Station as it appears in 2018. Zarya is visible at the center of the complex, identifiable by its partially retracted solar arrays.