Since the earliest days of flight, American women have been demonstrating and test flying aircraft. Throughout history, these special women have made their dreams come true with a determination that stemmed from their affection for flying machines.

In the past, women aviators such as Harriet Quimby, the first American woman aviator; Bessie Coleman, first black woman aviator in America (who, by the way had to get her license in France because of her color); Amelia Earhart, internationally renowned woman aviator, and founder of the Ninety-Nines; and Jacqueline Cochran, founder of the WASP’s; all had perseverance and resolve.

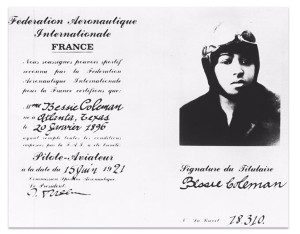

Coleman was the first African American (male or female) to receive an International pilot’s license. She was unable to find anyone in America who would teach her to fly because of her color.

Coleman was the first African American (male or female) to receive an International pilot’s license. She was unable to find anyone in America who would teach her to fly because of her color.

Bessie Coleman was born on Jan. 26, 1892, in a one-room, dirt-floored cabin in Atlanta, Texas. Growing up she always told her mother that she was “going to amount to something.” She went to school in a one-room schoolhouse and learned to read. At night she would read to her illiterate mother and her younger brothers.

After completing eight years of school, she became a laundress and saved her money until 1910, when she left for Oklahoma to attend college. After one year of college, she ran out of money and went back to being a laundress.

In 1915, she moved to Chicago to live with an older brother and became a manicurist. During that time, she was able to pay for a place of her own to live and decided her goal in life was to become an airplane pilot.

She was able to befriend several African American community leaders in Chicago’s Southside and met Robert Abbott, who became her sponsor. Abbott, publisher of the largest African American weekly newspaper, encouraged her to go to France to pursue her goal of obtaining a pilot’s license. He funded her trip to France in late 1920 and she earned her Federation Aeronautique Internationale (F.A.I.; international pilot’s license) license on June 15, 1921. Her first flight lesson was in a Nieport 82, a single-engine biplane built for combat during World War I. She then traveled Europe gaining additional flying experience so she could perform in air shows and became a dazzling air show performer before returning home to America.

In New York, she gave many interviews to the press and was given the nicknames of “Brave Bessie” and “Queen Bess.” She told reporters that she would be a leader for her race and encourage children to fly. She wanted to have a flying school for everyone. She spoke in churches, schools and theaters to inspire and foster the idea of African Americans to learn about and partake in the joy of aviation. She often would say, “The air is the only place free of prejudices.”

In New York, she gave many interviews to the press and was given the nicknames of “Brave Bessie” and “Queen Bess.” She told reporters that she would be a leader for her race and encourage children to fly. She wanted to have a flying school for everyone. She spoke in churches, schools and theaters to inspire and foster the idea of African Americans to learn about and partake in the joy of aviation. She often would say, “The air is the only place free of prejudices.”

In 1923, Coleman purchased a small plane but crashed on the way to her first scheduled West Coast air show. The plane was destroyed and Coleman suffered injuries that hospitalized her for three months. Returning to Chicago to recover, it took her another 18 months to find financial backers for a series of shows in Texas.

After recovering from her injuries, she went out to find backers of her air shows and after 18 months was able to purchase another aircraft. Her air show flights and theater appearances were successful and in 1925 and she was beginning to see that she would be able to earn enough money to start her aviation school.

She had a benefit demonstration scheduled for May 1, 1926m in Orlando, Fla., for the Jacksonville Negro Welfare League. She took the train to Orlando and pilot, William D. Wills, flew her two-place plane into Orlando. He had to make three forced landings because the plane was so worn and poorly maintained.

The day before the event, Wills and Coleman took the aircraft up for a trial flight to check the area where she was to do a parachute jump. She was in the back seat and Wills was piloting. She didn’t have her seatbelt on, as she wanted to be able to look out over the edge of the cockpit to see the surrounding area clearly and choose the best landing area for her jump.

For some unknown reason, Wills must have lost control of the airplane and it nosed over in a dive, flipped over, throwing Coleman out of the aircraft. Moments later Wills crashed and both were killed.

It was a tragic ending to a career of a determined, intelligent and beautiful young Black woman. Through the years, after her death, she achieved the recognition deserved for her contributions to the early days of women in aviation.