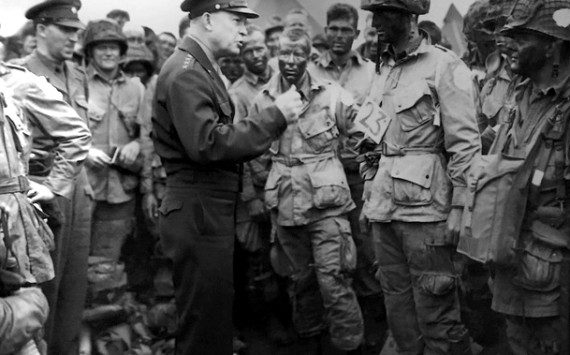

It must have looked like ceremonies many of us in the military attended at different times, with a troop formation standing in ranks, rendering salutes, and the official retirement of a unit flag, an unfurled flag being rolled up and furled.

That was March 29, 1973, in the vicinity of Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon, South Vietnam.

For more than a decade, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, known to most as “MAC-V” had also been nicknamed “Pentagon East,” its 12 acres of buildings had been the hive and nerve center of America’s long war in Vietnam.

Under the Paris “Peace Accords,” all combatant nations’ service personnel were to be out of the country within 60 days, leaving a, by comparison, minute American military presence. The war was handed over to the government of the Republic of South Vietnam. That government, the one we supported, would hang on for another two years, until shortly after President Richard Nixon resigned in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal, and Congress lost its will and interest in funding massive arms resupply to South Vietnam.

The communists prevailed, but many South Vietnamese who fled became great Americans. Ironically, Vietnam and Americans are now allies to check China’s threat in the Indo-Pacific.

The date, March 29, was selected and former President Barack Obama pronounced it National Vietnam War Veterans Day, the day Vietnam-era veterans are officially recognized by the nation for their service. Former President Donald Trump signed it into law.

In many ways, it was a war fought, more or less willingly by young Americans drafted into service. That is why at the point when more than 58,000 of them were killed in action, the last big push was on to get our POWs home from the “Hanoi Hilton,” one of the world’s most notorious prison camps.

A dear friend, retired Col. Joe Kittinger, who died last year, was one of the Air Force pilots held at the Hanoi Hilton, and he was one of the bravest and funniest men who were ever tortured there. “Lousy hotel,” Joe said. “Nothing to recommend it. No room service, the food was terrible. Don’t go there if you can avoid it.” That is called resilience. He also made free fall parachute jumps from space. So, brave.

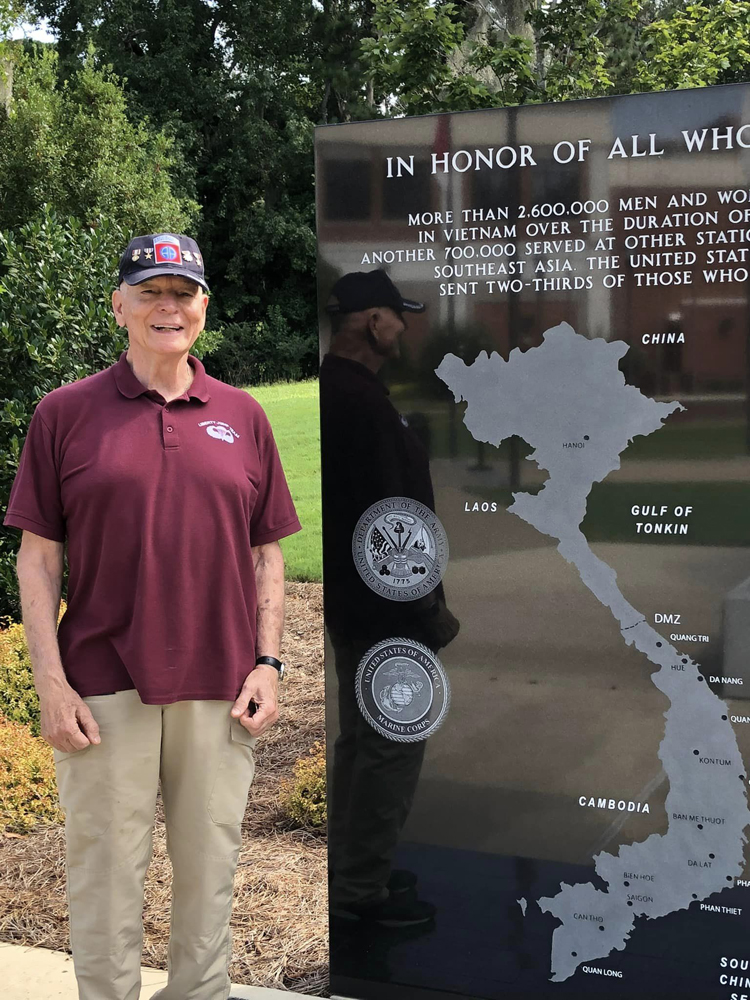

A friend and comrade of 50 years, retired Col. Stuart Watkins, labored for MAC-V as a paratrooper adviser officer to the South Vietnamese Airborne.

“They were good troops, good fighters, fought hard,” Watkins recalled. “If they were lucky, they got out of Vietnam at the end in 1975. Some of the finest people.”

The last two Americans killed in actions were U.S. Marines helping South Vietnamese allies board aircraft to escape Saigon as the Soviet-backed Army of North Vietnam poured into the besieged capital.

I joined the new “All Volunteer” Army about a month after the MAC-V flag rolled up and as the first POWs were coming home. There should be nothing but love, compassion and respect for the 2.7 million Americans who served in Vietnam.

Many draftees and regulars lived lives interrupted, about 30 percent burdened by Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that distressed their sleep and emotions for decades. March 29 is as good a day as any that might have been picked to show them some of the love they did not feel when they came home to a nation weary of a war in which most were lucky enough to never serve, but the vast majority who went served honorably.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is a licensed clinical social worker at High Desert Medical Group. An Army veteran, he deployed to Iraq with California National Guard to cover the war for the Antelope Valley Press. He works on veteran’s mental health issues.