South Korean service members salute a box containing a set of remains from the Korean War during the Korean War Remains Repatriation Ceremony at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, July 25, 2023. The purpose of the ceremony was to transfer the remains and commemorate the service of seven fallen South Korean soldiers who fought alongside U.S. and United Nations forces during the Korean War.

More than 500 family members of U.S. service members missing in action during the Korean War and the Cold War gathered in Arlington, Va., last week to get updates on the status of their loved ones, hoping that the remains have or will be located and identified and so bring answers after more than seven decades of waiting.

Every year for the last 30 years, leaders and forensic experts from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency have been briefing families of the missing on the status of searches and identification of service members’ remains.

Each family is provided an individual case summary on the status of their missing loved one, said Kelly K. McKeague, agency director.

During these visits, family members who haven’t yet done so are asked to provide DNA samples to further help in identification. Personnel are on hand to take DNA samples from cheek swabs, he said, noting that DNA samples from distant relatives are also useful in the identification process.

For some attendees, the agency will have much progress to share. For others, not so much, he said.

Lack of progress is mostly because the agency hasn’t been allowed to search for remains in North Korea since 2005, although North Korea did turn over remains that they excavated five years ago, he said.

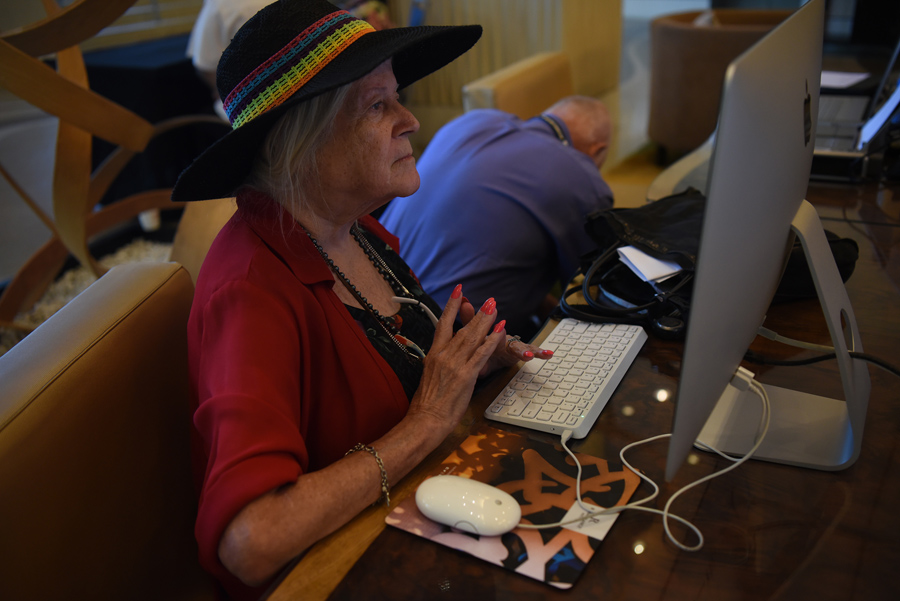

Donna Knox speaks to attendees at a Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency event to address missing service members from the Korean War and other Cold War periods. The event took place in Arlington, Va., Aug. 17 and 18, 2023.

Veronica Keyes, a forensic anthropologist with the agency and Korean War identification project leader, was one of four scientists who traveled to North Korea to repatriate the remains contained in 55 boxes that North Korea turned over in 2018.?

It was the last time North Korea turned over remains to the agency, she said.

During her visit to North Korea, the North Korean soldiers and forensic anthropologists were very friendly and eager to chat with the American visitors. It’s sad that the government of North Korea has cut off communications with the agency, she said, adding that she hopes there’s a change of heart since it’s a humanitarian endeavor.

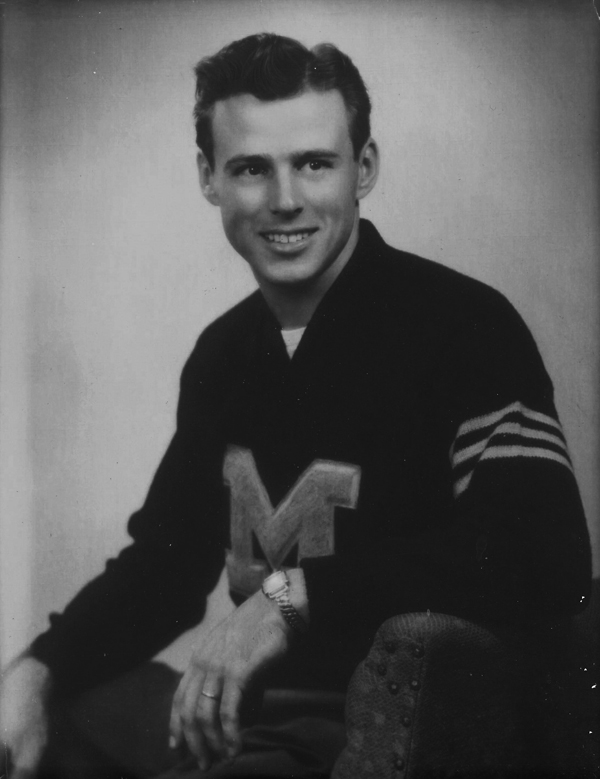

Donna Knox was one of the family members attending the event Aug. 17-18. She was not yet born when her father, Air Force 1st Lt. Hal Downes, crashed over North Korea on Jan. 13, 1952. Two months later, she was born.

Lee Downes, Knox’s mother, said that her husband, a navigator on a B-26 Invader was “vibrant, loving, devoted and the love of her life.”

For years, the family expected Downes to show up at the door to their house, Knox said.

In 2001, Knox visited North Korea. A North Korean soldier pointed to a rice paddy where he said the airplane carrying her father crashed. Knox said she spent some quiet time at that site reflecting on the father she never knew.

Knox said that she stayed at a guest house by a river in North Korea where a flock of cranes had gathered. A North Korean soldier said the crane is a symbol of eternal life.

When Knox boarded her flight out of North Korea, a crane flew alongside her window as the plane took off. Knox said that moment was very special for her.

Knox is one of the founders of a website promoting accountability for service members missing from Korea and the Cold Wars. It is: https://www.coalitionoffamilies.org/.

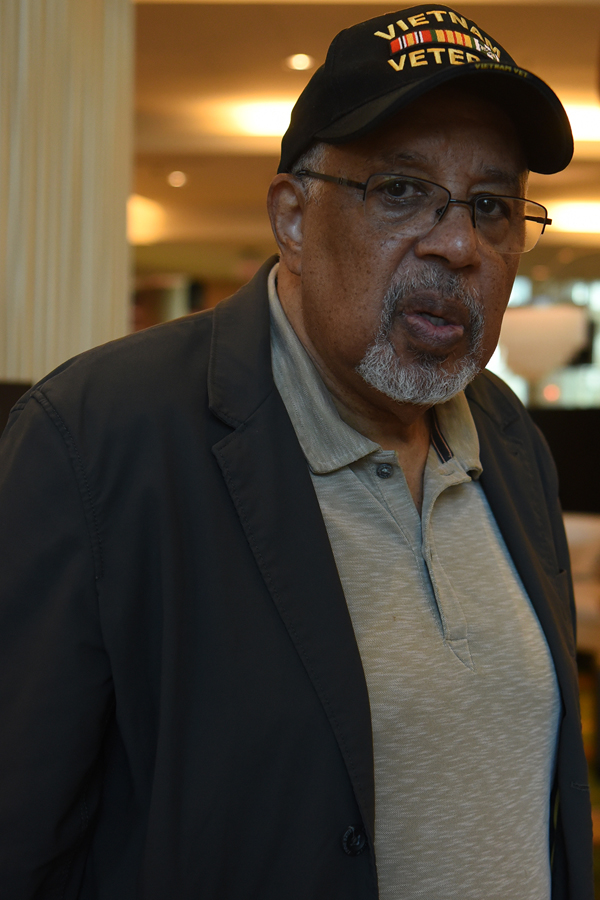

Another attendee was Eugene Fulmore, nephew of Army Cpl. Bannie Harrison Jr., who died while a prisoner of war in North Korea on Jan. 7, 1951. His remains were never recovered.

Fulmore said he was too young to remember his uncle, but he heard from family that he and his brother were among their uncle’s favorites.

Perhaps having an uncle who served and sacrificed led Fulmore to join the Army, he said. He served from 1966 to 1968, and in 1967, he was in South Vietnam.

Cynthea Grisham, another attendee, lost her father, Air Force Capt. David H. Grisham, on Sept. 3, 1950. He was flying an F-51 Mustang that crashed over the Sea of Japan en route to Korea. His remains were never found.

Grisham said she treasures photos of her father; she said he looked like actor Clark Gable. Capt. Grisham was also a B-24 Liberator pilot during World War II.

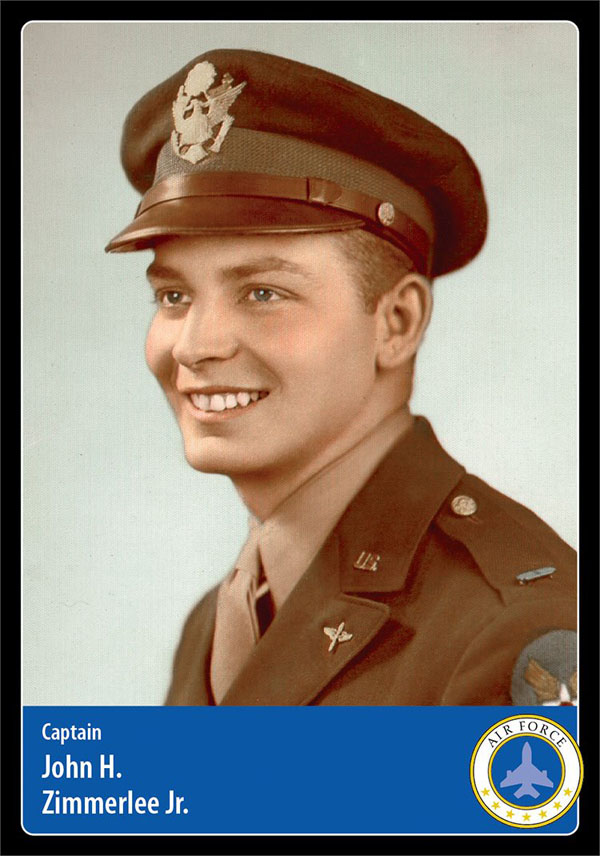

John Zimmerlee lost his father, Air Force Capt. John Henry Zimmerlee Jr., on March 21, 1952. Capt. Zimmerlee crashed over Singye, North Korea, while flying in a B-26 Invader as a radar observer. His remains were never recovered.

Air Force Capt. David H. Grisham, missing in action in Korea.

Zimmerlee has spent countless hours at the National Archives, trying to find more information about his father and seeking closure. He said too many files there are still classified, making the job difficult. He has also been helping to find files of others missing in action from the Korean War.

Capt. Zimmerlee was also a pilot during World War II, serving in Europe.

McKeague said there are 7,491 service members still unaccounted for from the Korean War. Currently, 666 have been identified. Of the 7,491 unaccounted for, the agency estimates that around 5,300 are still in North Korea.

During the identification process, some are discovered to be Chinese, South Korean or North Korean soldiers, he said.

North Korea has not expressed an interest in repatriating the remains of its soldiers, he said, but China and South Korea have.

In a recent case, the agency turned over the remains of a South Korean private first class.

A repatriation ceremony was held in South Korea and attended by the South Korean president, he said.

Also attending the Arlington event was the nephew of the South Korean soldier who died. The nephew is a chief petty officer in the South Korean Navy, he said.

The younger brother of the fallen South Korean private first class read a letter during the ceremony.?

“Welcome home, brother. It’s been too long. I want you to know that your sacrifice enabled me to be raised in a prosperous, free country,” the brother said, according to McKeague.

“You’ve often heard the Korean War called ‘The Forgotten War.’ It is not,” he said.

South Korea invites the U.S. families of Korean War MIA to visit South Korea, all expenses paid. South Koreans are appreciative of the service and sacrifices made by U.S. service members. They want to make clear that those sacrifices were not in vain as South Korea is a democratic and prosperous nation thanks to them, the young man said.

McKeague noted that his agency also searches for and identifies the remains of other wars, from World War II to Operation Iraqi Freedom. “We do this in 45 nations, including Russia and China. The second part of our mission is to connect and communicate with families of the missing.”