The headline “What Veterans Day Means to Me” sounds like a class assignment, and I have no doubt that is the case because hundreds of children have gifted me with thoughtful notes that began with that specific phrase, along with heartfelt “Thank You” sentiments attached, like, “Thank You for being a brave Soldier.”

I love those notes, and it must follow, love the kids who write them in child-like, spidery scrawls. Boys tend to draw tanks and paratroopers, and I was a paratrooper who ended up in tanks, so it all works for me.

For Aerotech News and Review, I promised an article about the National World War I Museum in Kansas City, Mo., so my intention is for this to hold some shelf life beyond the federal holiday described as Veterans Day.

Until about a year after I was born in 1953, Veterans Day was known as Armistice Day. It happened on Nov. 11, and it was intended to observe the end of World War I, also known as “The Great War,” and mistakenly dubbed “The war to end war,” a concept repeatedly discredited in the century since “the day the guns fell silent,” at 11 a.m., on Nov. 11, 1918.

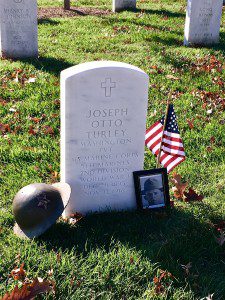

On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the eleventh 11th — Armistice Day — my grandmother’s brother, Joseph Otto Turley, lay dying in a field hospital. Tagged with a note classified “Gunshot Wound Severe,” he would never see the peace he helped to secure. As the battle weary but still lethal German army made a fighting retreat on the east shore of the Meuse River, my great uncle was fatally shot, among hundreds of Americans killed in the Great War’s final hours.

Five years ago, on Veterans Day 2018, my son Garrett P. Anderson and I were at Arlington National Cemetery. Our kinsman, Otto Turley, was returned in the battered form of his final remains, from France to Arlington in 1921. Many of the approximately 55,000 Americans killed during about six months of hard fighting in France in 1918 were buried near where they fell. The nation’s demand to have the remains returned to American soil became the most expensive undertaking project to date, and Otto Turley’s closed casket arrived at Arlington.

An error in records mis-dated our kinsman’s death date, and for more than 90 years that erroneous date, Nov. 2, 1918, marked his grave. My grandmother, Hattie Turley Anderson, carried a weight of sadness all her 91 years, with her brother’s solemn service photo on the mantle. Her memory was simple, clear, and accurate, “He was killed on the last day of the war.” I remembered that.

We believe his grave was never visited by family throughout the 20th century. Sadness and grief, possibly, but more likely most people did not make expensive transcontinental trips by rail in the early 20th century. There was a Great Depression, then World War II. So, the death date remained in error until my son, and I, partnered up to research the matter early in the 21st century when Garrett returned from combat with the Marines in Iraq and Afghanistan.

To discover what happened to Otto, a Marine killed at Armistice, became a passion project for my son who fought in Fallujah, and me, an Army paratrooper who studies war and tries to help the people who fight them and survive. They are the veterans we honor on Veterans Day.

Our research proved to Arlington cemetery leadership that the date on Otto’s headstone was wrong. So, the government did the right thing, and made a new headstone. My son and I were there to consecrate it on the 100th anniversary of the Great War that took our uncle’s life, and millions more lives from 1914 to 1918.

Five years on, my son and I make visits to Arlington to pay our respects to Otto – and also to Section 60 where a number of Garrett’s comrades from war in Iraq and Afghanistan are buried.

As Otto’s life bled out, Kaiser Wilhelm, who did much to ignite the global war, abdicated and fled to Holland. A dozen or so years after that, Germany embraced a World War I veteran, Adolf Hitler, as their savior and Fuhrer, and my father, Carl Richard Anderson, joined the 16 million Americans who served in World War II – 60 million deaths in that one. My grandmother must have been terrified that having lost a brother, she might also lose a son. My father lived, so here I am.

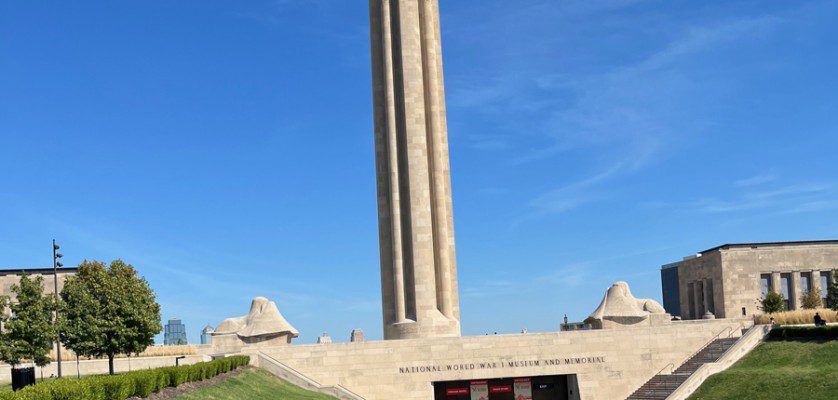

In Kansas City, an Egyptian revival style towering obelisk dominates the skyline. The 217-foot tower is the Liberty Memorial, commemorating the end of World War I. The site was dedicated in 1921, with 100,000 people gathered. After the Great War, Midwest donors raised $2.5 million in a couple of weeks, equivalent of $40 million today, to fund the Liberty Memorial.

More significantly, also attending the 1921 site dedication was Army Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, and Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in World War I.

In 1918, the war’s final months, Foch tried to break up the AEF and feed Americans into the ghastly trench warfare piecemeal under foreign command. Pershing refused – Americans would fight under American command, or not at all.

“I insist,” Foch asserted. “Insist all you like,” Pershing responded. Americans, the last big batch to enter the global calamity, served, fought, and died, together.

Three of our family members, Otto, Tom and Jess Turley, fought as Marines in France. Tom and Jess, both wounded, made it home, never to recover from their brother’s death at Armistice. Bachelors, they lived across the street from one another for 50 years and died months apart in 1971.

On the day the Liberty Memorial site was dedicated, earlier disputes between Pershing and Foch receded in the glow of fellowship. When the Memorial monument was completed in 1926, President Calvin Coolidge attended before a crowd of 150,000.

Today, the 80,000 square foot museum site hosts America’s greatest collection of artifacts, more than 350,000. It is also a research Mecca covering the entire conflict and our nation’s role that foreshadowed the emergence of the United States as a superpower. History informs us the Great War left such unfinished business that it paved the way to World War II, a much greater catastrophe.

In 1954, so many veterans filled the nation, Armistice Day became Veterans Day.

Passing through the museum’s galleries, the visitor views dioramas of the hideous trenches that were the graveyard of millions of young men. Posters emblaze all the propaganda and public relation machineries of impending modernity – and many exhibits that portray the role of women as nurses, volunteers, and telephone operators. The war ushered in the tank, combat aviation, fighters and bombers, chemical warfare, rapid-firing artillery and guns called “machine guns,” because they sprayed death on an industrial scale.

A uniform display shows the khaki combat kit of the 2nd Infantry Division worn by our three kinsmen, the Turley brothers.

What does Veterans Day mean to me? It means that my grandmother Hattie was always sad, even though gentle, and tough. Armistice means the war is not over. It is just a break before fighting starts again. It means veterans should be respected, and as Abraham Lincoln put it, we have a responsibility to the ones who bore the battle, and to the care of their surviving families.

More than 100 years later, it means I am still sad my great uncle was killed at the end, glad my father and son survived the wars they served in. Also, I know millions deal with this dread, grief, and anxiety daily.

The United States is the most powerful nation on Earth, economically and militarily. This means we have a responsibility to do everything we can to prevent the victory of tyranny, and to promote a just peace anywhere we can with anyone who will listen. Will anyone listen?

Editor’s note: The World War I Museum and Liberty Memorial is located at 2 memorial Drive in Kansas City, Missouri. For more information, visit www.theworldwar.org.