After the United States entered World War II in 1941, Frank Borman’s parents found work at a new Consolidated Vultee aircraft factory in Tucso, Ariz. His first ride in an airplane had been when he was five years old. He learned to fly at the age of 15, taking lessons with a female instructor, Bobbie Kroll, at Gilpin Field. When he obtained his student pilot certificate, he joined a local flying club. He also built model airplanes out of balsa wood.

Borman was helping a friend build model planes, when his friend’s father asked him about his plans for the future. Borman told him that he wanted to go to college and study aeronautical engineering, but his parents did not have the money to send him to an out-of-state university, and neither the University of Arizona nor Arizona State University offered top-notch courses in aeronautical engineering at that time. His football skills were insufficient to secure an athletic scholarship, and he lacked the political connections to secure an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He therefore planned to join the Army, which would allow him to qualify for free college tuition under the G.I. Bill.

His friend’s father told him that he knew Richard F. Harless, the congressman who represented Arizona. Harless already had a principal nominee for West Point, but Borman’s friend’s father convinced Harless to list Borman as a third alternative. Borman took the West Point entrance examination, but since his chances of a West Point appointment were slim, he also took the Army physical, and passed both. But the end of the war had changed attitudes towards joining the military, and the three nominees ahead of him all dropped out. Instead of reporting to Fort MacArthur, Calif., on graduation from high school, he went to West Point.

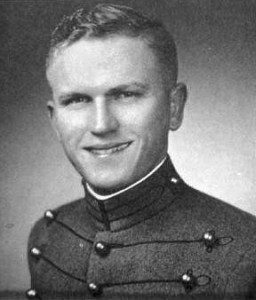

Borman entered West Point on July 1, 1946, with the Class of 1950. It was a difficult year to enter. Many members of the class were older than he, and had seen active service in World War II. Hazing by the upperclassmen was common. Another challenge was learning how to swim. He tried out for the plebe football team; his skills were insufficient, but head coach Earl Blaik took him on as an assistant manager. In his final year, Borman was a cadet captain, commanding his company, and manager of the varsity football team.

Borman chose to be commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force on June 2, 1950. Before the United States Air Force Academy was built, the Air Force was authorized to accept up to a quarter of each West Point graduating class. So that USAF officers graduating from West Point had equal seniority with those graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy, the entire class was commissioned four days ahead of their graduation. Borman graduated with his Bachelor of Science degree on June 6, 1950, ranked eighth in his class of 670.

Borman drove back to Tucson with his parents in his brand-new Oldsmobile 88 for the traditional 60-day furlough after graduation. He had split up with Susan while he was at West Point, but had since reconsidered. She had earned a dental hygiene degree at the University of Pennsylvania, and was planning to commence a liberal arts degree at the University of Arizona. He persuaded her to see him again, and proposed to her. She accepted, and they were married on July 20, 1950, at St. Philip’s in the Hills Episcopal Church in Tucson.

After a brief honeymoon in Phoenix, Ariz., Borman reported to Perrin Air Force Base in Texas for basic flight training in a North American T-6 Texan in August 1950. The top students in the class had the privilege of choosing which branch of flying they would pursue; Borman elected to become a fighter pilot. He was therefore sent to Williams Air Force Base, near Phoenix, Ariz., in February 1951 for advanced training, initially in the North American T-28 Trojan, and then the F-80 jet fighter. Fighter pilots were being sent to Korea, where the Korean War had broken out the year before. He asked for, and was assigned to, Luke Air Force Base, Ariz., — Susan was eight months pregnant — but at the last minute his orders were changed to Nellis Air Force Base, Nev. There, he practiced aerial bombing and gunnery. His first child, a son called Frederick Pearce, was born there in October. Borman received his pilot wings on December 4, 1951.

Soon after, Borman suffered a perforated eardrum while practicing dive bombing with a bad head cold. Instead of going to Korea, he was ordered to report to Camp Stoneman, Calif., from whence he boarded a troop transport, the USNS Fred C. Ainsworth on Dec. 20, 1951, bound for the Philippines. Susan sold the Oldsmobile to buy air tickets to join him. He was assigned to the 44th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, which was based at Clark Air Base, and commanded by Maj. Charles McGee, a veteran fighter pilot. Initially, Borman was restricted to non-flying duties due to his eardrum; although it had healed, the base doctors feared it would rupture again if he flew. He persuaded McGee to take him for flights in a T-6, and then a Lockheed T-33, the trainer version of the Shooting Star. This convinced the doctors, and Borman’s flight status was restored on Sept. 22, 1952. His second son, Edwin Sloan, was born at Clark in July 1952.

Borman returned to the United States, where he became a jet instrument flight instructor at Moody Air Force Base, Ga., mainly in the T-33. In 1955, he secured a transfer to Luke Air Force Base, Ariz. Most of his flying was in F-80s, F-84s, swept-wing F-84Fs and T-33s.

In 1956, he received orders to join the faculty at West Point, after first completing a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. Not wanting to spend two years qualifying for a non-flying posting that could last for another three years, he searched for a master’s degree course that took only one year, and settled on the one at the California Institute of Technology. He received his Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering in June 1957, and then became an assistant professor of thermodynamics and fluid mechanics at West Point, where he served until 1960. He found he enjoyed teaching, and was still able to fly a T-33 from Stewart Air Force Base, N.Y., on weekends. One summer he also attended the USAF Survival School at Stead Air Force Base in Nevada.

In June 1960, Borman was selected for Class 60-C at the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and became a test pilot. His class, which included Michael Collins and James B. Irwin, who also later became astronauts, graduated on April 21, 1961. Thomas P. Stafford, another future astronaut, was one of the instructors. On graduation, Borman was accepted as one of five students in the first class at the Aerospace Research Pilot School, a postgraduate school for test pilots to prepare them to become astronauts. Fellow members of the class included future astronaut Jim McDivitt. Classes included a course on orbital mechanics at the University of Michigan, and there were zero-G flights in modified Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker and Convair C-131 Samaritan aircraft. Borman introduced training with the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. It would be flown up to 70,000 feet, where the engine would cut out for lack of oxygen, and then coast up to 90,000 feet. This would be followed by a powerless descent, and restarting the engine on the way down. A pressure suit was required.

On April 18, 1962, NASA formally announced that it was accepting applications for a new group of astronauts who would assist the Mercury Seven astronauts selected in 1959 with Project Mercury, and join them in flying Project Gemini missions.

The Air Force conducted its own internal selection process, and submitted the names of 11 candidates. It ran them through a brief training course in May 1962 on how to speak and conduct themselves during the NASA selection process. The candidates called it a “charm school.”

Borman’s selection as one of the Next Nine was publicly announced on Sept. 17, 1962. Chuck Yeager, the commandant of the USAF Test Pilot School at Edwards, told him: “you can kiss your godamned Air Force career goodbye.” During his Air Force service, Borman logged 3,600 hours of flying time, of which 3,000 was in jet aircraft.