PENDLETON, Ore. — The C-47 aircraft we jumped from, “Betsy’s Biscuit Bomber,” was built during World War II, and it was roaring along at 100 mph, 1,500 feet above ground level on final approach to the drop zone.

Within a minute, I was dropping with paratroopers into farmland north of Pendleton Airport in rural, eastern Oregon. We were jumping in 2024 to honor a unit of black servicemen of World War II less known to history than the famed “Tuskegee Airmen.” The men of the “Triple Nickle” pioneered firefighting by parachute.

My landing, with a jolt, was hard enough. But I landed softer than the “Triple Nickle” paratroopers who jumped into trees and canyons to battle a desperate effort by Japan to set the West Coast on fire at the end of World War II.

Dozens of paratroopers in our aircraft on a fine, spring day were jumping to commemorate the historic 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. They were the unheralded heroes of Operation Firefly, a secret mission near the end of the war in which the enemies were Japanese incendiary bombs, wildfires, and racism.

Nearly 80 years after the end of history’s biggest war, our World War II vintage aircraft carried parachutists on current active duty with the 82nd Airborne Division. Lined up in the aircraft with them were veterans of a broad spectrum of race and gender, some of them “Smoke Jumpers” of the National Forest Service joined by paratroopers from Europe and Canada.

Standing at the aircraft door, the Jumpmaster shouted the final command, “Go!”

Parachutists handed their yellow static lines that would yank their chutes open to the jumpmaster. Their canopies billowed into the C-47’s prop blast at one-second intervals, the jumpers descending the same way Allied Airborne troops did on D-Day into Normandy.

Watching from the ground below us were hundreds of people, some of them descendants and family of “Triple Nickle” paratroopers.

The “Greatest Generation” troopers of the “Triple Nickle” boarded similar aircraft in 1945 at the same airfield for their mission in the original Operation Firefly.

“We were happy you honored us,” said Garrett Godfrey, a career Army veteran and member of the “Triple Nickle” 555th Parachute Infantry Association, a nonprofit group that celebrates the unit’s legacy. “It was beautiful.”

Soldiers of the “Triple Nickle” were trailblazing black paratroopers who jumped into the fire of World War II conflict without ever leaving the United States.

The “Triple Nickle” paratroopers probably rank as the bravest soldiers who never waged war overseas. As Robert Bartlett, a scholar of their unit put it, “They jumped into the fire of war, and jumped into the fire of civil society.

“Their service involved service, sacrifice, patriotism, and they faced blatant racism,” Bartlett, a sociology professor at Gonzaga University, said.

With preparations for D-Day under way, the Army organized the unit only after President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Airborne training at Ft. Benning, Ga., and pointedly asked “Where are your Negro paratroopers?”

Because of ties by Army heritage to black “Buffalo Soldiers,” of the 92nd Infantry Division, and because of the 555th unit designation, the group adopted “Buffalo” nickel coins as their talisman. Bartlett noted the unit was given little support, and had to recruit unit members from the segregated ranks “by finding only the best.”

“President Roosevelt’s Negro Advisory Group told him, ‘Our men want to serve in combat, not patching holes and serving in the cook house,’” Bartlett said.

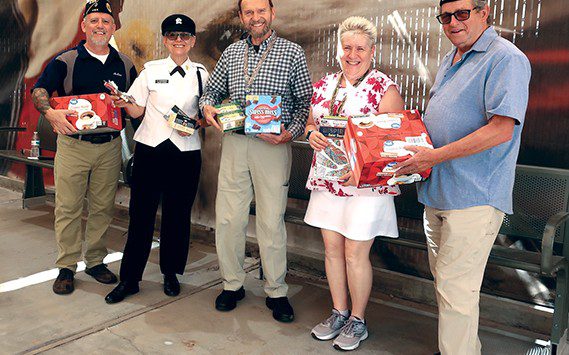

The weekend of honors, including parachute drops over Pendleton Airport, was organized by the All Airborne Battalion, a historical non-profit. The three-day event included recognition ceremonies and history presentations.

Seeing the Triple Nickle group’s legacy honored became a passion project that was months in preparation, according to event organizer Jordan Bednarz, a member of the All Airborne Battalion’s commemorative jump team.

“We did this to honor the legacy of this group of these brave Americans whose story is still largely unknown,” said Bednarz, an Army paratrooper veteran. “The honor was long overdue.”

During a public ceremony, Darren Miguel Cinatl, president of the All Airborne Battalion nonprofit, joined with Bednarz and Triple Nickle family descendants to dedicate the land surrounding Pendleton Airport as the Malvin Brown Drop Zone.

“This is truly hallowed ground, said Cinatl, who served as a captain with the 82nd Airborne Division in Afghanistan. “We are honored to join with you in this recognition of these true American heroes.”

The 555th battalion’s mission included more than 1,200 wartime drops into the mountainous forests of the Pacific Northwest. The “balloon bomb” offensive became Japan’s last effort to bring the war home to American shores.

Malvin Brown, a private first class medic, was the only soldier killed in action, falling to his death, exhausted after landing in a tree too tall to climb down.

The 555th paratroopers believed they were headed to war in the Pacific, but got no further than Oregon. Secret orders directed the unit to suppress Japanese incendiary bombs, floated by the thousands, toward the West Coast. Army records indicate several hundred made landfall, but only a few succeeded in sparking blazes. Secrecy was maintained to prevent civilian panic.

Neither trained or equipped to fight wildfires or deactivate bombs, the 555th paratroopers exchanged infantry weapons for shovels, and were trained by conscientious objectors drafted as firefighters into the U.S. Forest Service.

“To be a smoke jumper takes six weeks of training,” Bartlett recounted. “The Triple Nickle paratroopers had only nine days.”

In the multitude of wartime losses, paratrooper Brown fell to his death on the same day the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, Bartlett noted. Other troops sustained injuries in jumps to their backs, legs, and pelvis.

“These men were volunteers, who wanted to fight … trained by conscientious objectors who did not want to fight in a war. There is an irony,” Bartlett said.

“The bets were on that they would fail, bets from white jumpers and cadre, that they were not brave enough, not smart enough,” Bartlett said. “The bet was that they wouldn’t make it. … Of course, they made it.”

Like most black troops in World War II, they faced entrenched racism, Bartlett noted in a presentation to the groups that gathered at Pendleton the weekend of April 12-14. Standing by a table of vintage firefighting gear he collected, Bartlett shared the story of the pioneering “smoke jumpers.”

The work was exhausting. On the day Brown was killed, his brother paratroopers carried his body 14 miles on a litter.

Free time offered little respite. “They would be refused at restaurants and bars,” Bartlett said. “They could not get a room at a hotel.”

On April 13, at ceremonies to dedicate the Malvin Brown Drop Zone, family members and descendants of the 555th paratroopers turned out, joined by hundreds of people from the community of Pendleton.

“When I was young, I did not know our history, just that I wanted to be a paratrooper,” said Clarence E. Scott. “When I retired, I wanted to learn all about the history. I founded a chapter of the 555th Parachute Infantry Association.”

On a stage at the airfield, the Pendleton Chamber of Commerce welcomed family members of one of the last surviving members of the unit, Joe Harris. Harris’s grandson, Antonio Harris, held up a mobile phone on FaceTime so the crowd could cheer Harris from bed in his Compton, Calif., home.

“We call our grandfather ‘Daddy Joe,’” Antonio Harris said, holding the phone up for the cheering crowd. “We are looking forward to his 108th birthday.”

Antonio Harris was joined on stage by Harris’s granddaughters, Michaun Harris and LaTanya Pittman.

Among current active-duty paratroopers jumping to honor the World War II paratroopers was Capt. Jonathan Vann, an 82nd Airborne Division officer.

“As an African American officer, I make it a point to know our history,” Vann said. “The Triple Nickles always were significant. Primarily because I spent years as paratrooper and jumpmaster in the 82nd Airborne Division.

“The men who served in the Triple Nickle embodied resilience and determination. Even though they faced extreme racism, they still chose to defend the nation,” Vann said. “That is a true patriot.”

As Vann strapped his gear on, he was the first paratrooper out the door of the C-47 in one of its passes over the newly dedicated Malvin Brown Drop Zone.

“I am forever grateful to participate in this illustrious event,” Vann said.

In his book, “The Triple Nickles,” the late Bradley Biggs, one of the 555th’s leaders during World War II told a white officer that he wanted to be a paratrooper, “not to prove that a Negro can jump out of airplanes, but to prove it should have been this way all along.”

In one bright moment of America’s military moving on from a segregated force, Maj. Gen. James “Jumping Jim” Gavin, hero of D-Day, welcomed the 555th paratroopers into the 82nd Airborne Division, nicknamed the “All Americans.”

Gavin, Bartlett said, marched the unit in a World War II victory parade, and made them part of the division more than a year ahead of President Harry Truman’s order to integrate the armed forces.

“He loved those guys,” Bartlett said. “They were the best. They knew they had to be. They knew the stakes. Failure was not an option for them.”

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army paratrooper veteran who made commemorative jumps at Normandy on D-Day drop zones, also at Toccoa, Georgia, where the “Band of Brothers” of the 101st Airborne Division trained, and Pendleton, Ore., where the 555th Parachute Infantry was based during World War II.