LANCASTER, Calif. — One of the last times I saw experimental test pilot Dick Rutan was on a panel I emceed called “Going Downtown: The Air War in Vietnam.”

Aerotech News was a key sponsor of the Los Angeles County Air Show where Rutan shared the story of his last combat mission.

Rutan died May 3, 2024, age 85 in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. With his genius airplane designer brother, Burt, together, they make up the reason the tarmac of Mojave Air and Space Port is named “Rutan Field.”

Dick Rutan is remembered as the pilot who flew the airplane his brother designed, the flimsy looking but epically strong “Voyager” experimental aircraft around the world on a single tank of gas. Rutan flew with Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck Yeager) as co-pilot.

That was nearly 40 years ago. Voyager now is proudly displayed in the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum, another testament that Antelope Valley is the “Aerospace Valley and flight test capital of the world.”

The Rutan brothers won the Collier Award trophy for Voyager.

In the many episodes of Dick Rutan’s pilot story, his exploits as a combat pilot show who he was, and what he achieved. On his last mission in Vietnam, his aircraft was hit. His F-100 Super Sabre was on fire, and he nosed it toward the Gulf of Tonkin before ejecting.

“That was the day I joined the Gulf of Tonkin ‘Yacht Club,’” he said, floating in a survival raft until he retrieval by a search-and-rescue helicopter. Lifted by a cable hoist and deposited into the Air-Sea Rescue helicopter, Rutan was relieved, and thanked the air crew on board so they could hear above the rotor din.

“I knew I was going home — that I had made it,” he said.

Curling up on the chopper floor, he said “I wrapped myself in a blanket, and went to sleep.”

That was just another dot on the map of a hero’s journey. The man flew 325 missions in Vietnam. The unit he flew with, Misty FAC, lost more than a quarter of its pilots to enemy fire.

The mission was to fly low to spot enemy anti-aircraft batteries and fly close enough to “paint them” as targets for other aircraft called “Wild Weasels.” Misty FAC denoted “Forward Air Control.”

His combat flight record was valor defined. Rutan was awarded the Silver Star, four awards of Distinguished Flying Cross, with Valor device, 16 awards of the Air Medal for combat aerial operations, and, notably, the Purple Heart.

In his autobiography, Chuck Yeager wrote he once was tasked with telling younger Vietnam pilots that they had the best training, best planes, best chow, best liquor, and best girls. So, Vietnam’s air war was where they needed to steel themselves to fly low on course, and hit their targets. Rutan never needed that briefing.

His Air Force career began in 1959 shortly before John F. Kennedy was elected president. A young Rutan served as “radar intercept officer” and also as a flight navigator before he earned his silver Air Force pilot wings a half dozen years into service.

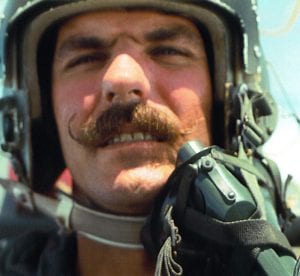

Once he turned fighter pilot, the man was a tiger with ammo strapped on. In Vietnam photos, he sports a non-regulation handlebar Wyatt Earp moustache straight out of “Tombstone.”

During the Vietnam flight panel, he mused aloud what he wanted to share with what was a packed tent of mostly awestruck admirers.

Rutan shared with the audience what he called “a little pseudo psychology” about combat. That mindset, he said, is “Kill, or be killed.” Destroy the enemy’s guns or be destroyed by them.

Adrenaline, Rutan said, is about running away from bears chasing you. Combat is about chasing the bear.

“The epitome of competition is one man against another,” he said. And that spirit is fueled by what Rutan called the “combat gland.”

“The combat gland has an addictive, euphoric effect,” Rutan said. “Every time you shoot, it’s kill or be killed. You want more, and you want more, and you want more.

“If you’ve lived your life without being shot at, you’re missing something,” he said. It is a physical component, particularly, he said, of the “testosterone-charged male.”

Few in that tent filled that description. They were mostly civilian dads and moms and kids, people who loved or worked aviation, people who loved history. Combat veterans, the guys with ball caps, nodded approvingly in their understanding of combat and its addictive quality.

Rutan was on stage with living history. Among the four other combat alphas who joined him was Col. Joe Kittinger, another legend.

At a reception the evening before the tent show, I saw Rutan greet the older man, Kittinger, like a long lost brother. He loved Joe Kittinger. They were two of a kind, Kittinger, portly, and Rutan, rangy. Brothers!

Kittinger had a couple of records. He set records as the first man to free fall from space. In August 1960, when Dwight D. Eisenhower was president, Kittinger jumped from a balloon at the edge of space, falling from 103,000 feet above ground level to test pressure suits for the space program.

After four combat tours in Vietnam, Kittinger also fell from the sky when his F-4 Phantom was shot down. He was sent to the notorious “Hanoi Hilton” prison camp for a year before the POW releases started in 1972. He held record as the “oldest new guy” in camp.

Kittinger recalls “I had studied at every survival and escape school there was, and I was going to hit the ground and evade for a year, make my way back.”

Instead, his parachute plopped him in a field filled with rice, and with North Vietnamese farmers. “About 50 of them swarmed my butt.”

They stripped his boots and flight suit, and took his pistol. Wobbling on a wounded left leg, “in my skivvies Ö the first thing an 80-year-old lady waved a knife at my neck, and I jumped back. The next thing, a 14-year-old boy did the same thing.”

Kittinger, like other surviving POWs, survived that parachute landing only because North Vietnamese troops arrived, pushing him into a truck to the prison camp that inspired dread in American pilots.

“It’s just the worst ‘Hilton’ in the world,” Kittinger joked to the tent full of aviation history buffs. “There’s no air conditioning, no room service. The food sucks. Don’t ever stay there.”

Their banter showed these were men who came close to laughing at death, and did laugh about it afterward, in each other’s good company.

First time I met Rutan for an interview at Mojave Airport for Associated Press in 1986 during the buildup of excitement for the Voyager Flight, he made it obvious he did not care for press. He was only putting up with us to help sustain support for the project.

A few weeks later, I stepped out on the tarmac at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., to shake his hand when Voyager completed its globe-girdling flight. Surrounded by a throng of admirers he was even more dismissive. He asked me, half-jokingly, if I was trying to snag his wristwatch.

More than 15 years later, I interviewed him when he was named Grand Marshal of a “Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans” parade in Lancaster. I don’t think he remembered me, but he saw my miniature silver Army paratrooper wings on my coat lapel, and he asked when and where I served. Cold War Europe, I replied, at a place called the Fulda Gap where it was believed the Soviets would invade in World War III.

He warmed up instantly. “There were things about the Cold War that were scary as Vietnam,” he said. “When you fly with a nuke strapped under your cockpit, it gets your heart racing.

“Cold War veterans have always deserved more recognition in my book,” Rutan said. And I agreed.

Our veteran bond cemented a mutual respect. At the Los Angeles County Air Show, he remembered, and his greeting was warm as mine, and I have never forgotten how he closed that afternoon’s event.

Rutan recalled the words of the American warriors’ most beloved leaders, Adm. Jeremiah Denton, the most senior officer of POWs, who was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Stepping off the returning jetliner at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, Denton spoke for the men he led during their captivity.

Rutan recited Denton’s words, saying “Every time I say this, I choke up.”

Quoting Admiral Denton, he recited “I consider it an honor to have had the privilege to serve my country under difficult circumstances.”

Rutan reflected, “I think about the totality of what he said, and I think to myself, ‘Who are these people, such remarkable people?’”

One of those people was Rutan. The other, Kittinger. Both achieved remarkable things, and both considered it a privilege to serve their country wherever their service took them.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army paratrooper veteran who deployed with California National Guard to cover the Iraq war for local and national publications. He serves on the Los Angeles County Veterans Advisory Commission.