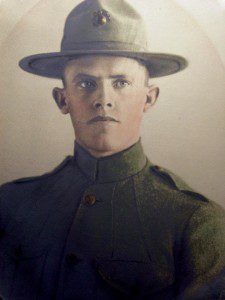

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY — Our kinsman, Joseph Otto Turley, was 24 years old when he was shot on the last day of World War I, one of hundreds dying in the final hours of the Great War before the guns went silent.

The former football player and student body president at Auburn High School in Washington State had come so far, serving on a machine gun team in three of the bloodiest battles of history’s bloodiest war to date.

He had survived the charge at Soissons, the bloody ascent at Blanc Mont, and America’s biggest battle in World War I, the Meuse-Argonne campaign. Unless you knew a Doughboy or a Marine, or had one in your family, these battles have faded with the mists of time.

Otto Turley had come so far, and would fall, a few hundred yards short of the finish line.

Nov. 11, 1918, was the final day of what was up to that time history’s biggest and most lethal war, that war ending between the Allies and the Central Powers led by Germany on the 11th hour, of the 11th day of the 11th month.

By that time my great uncle, my grandmother Hattie’s brother, was bleeding out and would die the next day in a church converted to field hospital.

My son, who served in combat with Marines in Iraq and Afghanistan, was certain that our ancestor suffered an agonizing and slow death. Turley’s “Died of Wounds” record indicated GWS, initials standing for “gunshot wound, severe.”

Our great Uncle Otto was mortally wounded in one of the final actions of the war, the crossing of the Meuse River, in which some hundreds of Marines wobbled across a makeshift wooden bridge cobbled together on the night of Nov. 10 by Army combat engineers.

Some of the Marines feared making the crossing, but most walked on after the captain who said, “I’m crossing that bridge, and I expect you men to follow me.”

Most did, and some were shot off the bridge, falling into the river and dragged under swift currents by heavy gear, drowned. The ones who made it to the far shore faced a steady hail of fire from Germans who were nearly beat, but still commanded high ground with machine gun and accurate rifle fire.

That fire continued past 11 a.m., the hour agreed for the Armistice, until a German officer and adjutant appeared with a white flag of truce, the German telling a Marine officer, “The Armistice has been in effect for hours. Will you tell your men to stop shooting at my men?”

Within hours, Germans and Americans were trading cigarettes, cigars, sausage “like long lost brothers,” one Marine recalled. Gen. John Lejeune, the Marine legend who was namesake of Camp Lejeune, lamented that so many were dead and dying on “the evening of peace,” our kinsman among them.

Two brothers served with “Uncle Otto.” They were Tom and Jess Turley, Marines all. By the time the war ended, Tom was evacuated with a gunshot wound to the chest, from which he would recover. Jess Turley and his Marines marched into Germany to begin a short occupation

That was the Armistice that ended World War I, to be commemorated as Armistice Day. And it remained that way until 1954, 70 years ago. We were in a fiery chapter of the long Cold War that consumed U.S. national security since shortly after the end of World War II.

Armistice Day would become Veterans Day. The United States retained a big draft military of millions of troops with global commitments, all serving to deter the prospect of a nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of D-Day in World War II, and architect of NATO, and the nuclear strategy of the Cold War, signed legislation in 1954 changing the commemoration to Veterans Day.

I have been for many years an American veteran, but my son was in active and highly hazardous service when we resolved to solve the mystery of our kinsman’s death at Armistice, Nov. 11, 1918. We decided by long distance call from California to Iraq. My son and I discussed this just as Lance Cpl. Garrett P. Anderson was heading into a fright show of combat at close quarters called “The Second Battle of Fallujah.” Fifty-two of his unit brothers would be killed in Iraq.

On a last phone call from Camp Fallujah, the staging area, my son said, “We have to find out about Uncle Otto. I think it’s important.”

My early childhood memory was my grandmother telling me “Your Uncle Otto was killed on the last day of the war.”

My guess was that Otto was a Doughboy, meaning an Army soldier, not a Marine. My son rebuffed that in our phone call from Camp Fallujah.

“Uncle Otto was a ‘Devil Dog,’ old man,” he said. “He was a Marine.”

He was certain, and it turned out he was correct. With Garrett home from the Post 9/11 wars, we found Uncle Otto’s grave at Arlington and visited, Section 18, Grave 1345.

When we first visited Arlington National Cemetery together in 2007, both of us now veterans, we found Pvt. Turley’s gravestone. We knew immediately that a grave error was contained on the stone. It listed our kinsman’s death date as Nov. 2 — not the battlefield death known to our family as the end of the Great War.

It would take 11 years and a change in leadership at Arlington National Cemetery after the resolution of record-keeping scandals to get the error on the gravestone corrected.

On Nov. 11, 2018, 100 years to the day after the end of World War I, my son and I, with family and our Marine Corps war on terror battle brother, Col. Jeffrey T. Wong, gathered graveside at Arlington. Cemetery officials had done the right thing and struck a new marble gravestone with the accurate date of death.

Why do these things matter? Because, in this way, we ensure that our dead, our fallen brothers and sisters, are not forgotten. That is why they marked the Armistice, the end of the greatest war in history to date.

And that is why we remember our brothers and sisters, living and dead, fallen and serving, and veterans all on Veterans Day.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army paratrooper veteran who covered the Iraq War for local and national media. He has served on the Los Angeles County Veterans Advisory Commission and works as veterans advocate at High Desert Medical Group.