ANZIO AMERICAN CEMETERY, Italy — Trips to honor fallen Americans can be as far as the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Italy — 6,400 miles— and as near as a monument on Lancaster Boulevard, about 20 miles south of Edwards Air Force Base in California.

Combat aviation has been part of the Edwards and Antelope Valley’s shared legacy since Gen. Curtis “Iron Eagle” Lemay was training World War II bomber crews to hit the mocked-up wooden battleship nicknamed the “Muroc Maru” on the arid hardpan of Rogers Dry Lake.

The monument on Lancaster Boulevard is on the “Aerospace Walk of Honor,” and it is dedicated to the renowned Tuskegee Airmen, the black fighter pilots of World War II who flew a blaze of glory over the angry skies of Nazi Germany, and, yes, Italy.

Before the “Red Tails” flew combat escort of bombers on the way to Berlin, they were bombing bridges and flying air support in Italy.

Among the pilots in the honor roll of the silver monument in Lancaster is Myron “Mike” Wilson, the Tuskegee Airman who teamed in shooting down a Nazi Messerschmitt 262, the world’s first operational fighter jet.

Wilson’s son, Raymundo Wilson, is a Los Angeles Sheriff’s Deputy who honors his father’s legacy overseeing a club of at-risk youngsters who assemble donated World War II aircraft models like the “Red Tail” P-51 Mustang his father flew in combat.

That legacy is why there’s a monument on Lancaster Boulevard that was propelled by former Mayor Henry Hearns, retired Bishop at the Cathedral of Living Stone, and living veteran of the Korean War.

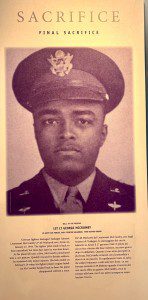

So, it was at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial, more than 6,000 miles from the Lancaster monument where I found the tribute to “Red Tail” Mike Wilson’s brother-in-arms, 1st Lt. George McCrumby.

McCrumby was killed Feb. 29, 1944, when the engine his P-40 Warhawk failed returning from a combat air patrol. Plane and pilot vanished without a trace. McCrumby is one of two Tuskegee Airmen honored at the Sicily-Rome cemetery a few short miles from the Anzio beachhead.

The 99th Fighter Squadron of the 70th Fighter Group, the “Red Tails” was a small outfit. Lt. McCrumby and Wilson likely knew one another, and certainly shared the dangers together, even though they could not buy a drink together unless it was at their own segregated officer’s club in a canvas tent. Desegregation of the military awaited President Harry Truman’s order, two years after the end of history’s biggest war.

McCrumby is among 7,860 Americans, soldiers, sailors, and airmen honored at the Sicily-Rome cemetery where the graves are tended with exquisite care, row on row of white crosses punctuated by the occasional Star of David.

I was greeted by Cemetery Director Mark Ireland, an Army veteran, who welcomed us with a smile and invitation.

“Is there anyone who we can help you find? Do you have a relative here?”

My wife, Julia, and I sought a gravesite of any soldier from the 45th Infantry Division, the outfit her uncle fought with, and any soldier from the 509th Parachute Infantry, one of the units I trained with during my Cold War service in Germany.

But why Anzio? What is its significance 80 years after the end of World War II?

Anzio was the biggest seaborne landing apart from D-Day. Allied war planners hoped to outflank the 100,000 Germans fighting for every foot of the Italian boot and liberate Rome quickly.

It took five months, 23,000 Americans killed and thousands more British and Commonwealth troops to clear the 50 miles to Rome in 1944. The Allies liberated the city a day or so ahead of D-Day in Normandy, so the epic achievement of the first Axis capital to fall was immediately overshadowed by events in France.

Still, these nearly 8,000 sons and daughters of America rest here, honored in the equality of the lives and families they gave up so all of us had a chance at a pretty great life.

The thousands of men and 17 women from Women’s Army Corps and Red Cross nursing never heard the term Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, but all of them were equal in the suffering of death before victory.

They were all colors, religions and creeds, and like the nickname of the 82nd Airborne Division, they were “All Americans.”

Two pilots from the Tuskegee Airman are buried or memorialized here, along with a member of the 442nd “Go For Broke” regiment of Japanese American soldiers who left internment camps in America where their families were incarcerated to serve or die for their country.

My wife Julia and I, grown children of World War II veterans, were welcomed to the splendid memorial park maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission by Army veteran and Director Ireland and his assistant Luca Tamberlani.

With care and courtesy the two guardians of the cemetery guided us to graves we were interested in, including Alfred C. Petzold of the 509th Parachute Infantry killed fighting after the jump into Sicily, the 509th being the unit I went through jump school with 30 years after Lucero’s combat death.

Others who landed at Anzio survived to return home and start families, launching that historic Baby Boom that I was born into.

The Anzio assault against the Nazi troops of Hitler and dwindling ranks of the Italian dictator Mussolini was as hard and miserable as war can be. More troops fell victim to malaria than were killed and wounded because the Nazis reflooded swamps that Mussolini had drained for farmland.

“They were cruel. It was a kind of biological warfare,” said our Italian friend Jonathan Trupia who accompanied us to Anzio with his sister, Beatrice, driving the 50 miles from Rome.

A few miles from the beach, the Anzio battlefield became a bloody stalemate and artillery duel that would not be resolved by Allied breakout late in the spring of 1944.

A little more than 81 years later at 5 p.m., as an American veteran, I was invited to join Ireland and Tamberlani in lowering the flag at taps.

There was wind and rain like the day the Allied troops of America and the British Commonwealth came off the ships on Jan. 22, 1944.

Flapping in the wind, the flag lowered slowly, a scant 50 miles from Rome, a price paid every mile by the lives of American and British soldiers, who traveled far from their homes as President Franklin D. Roosevelt put it, not to conquer, but to liberate a suffering humanity.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army veteran and embedded journalist of the Iraq War. An Antelope Valley journalist for 30 years, he has served on the Los Angeles County Veterans Advisory Commission.