National Security Act births AF

National Security Act births AF

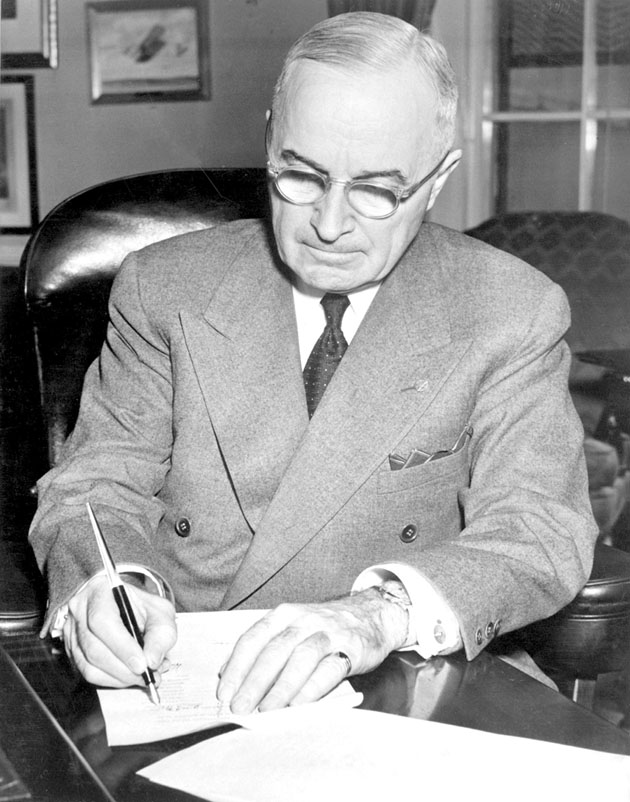

With the stroke of a pen, President Harry S. Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 on Sept. 18, 1947.

The Act created the National Military Establishment – later renamed the Department of Defense – and created the U.S. Air Force as a separate branch of the U.S. military.

The signing began a three-year transition period in which soldiers became airmen and army air fields became air force bases.

Before that, the responsibility for military aviation was divided between the U.S. Army for land-based operations and the U.S. Navy for sea-based operations.

And while we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the creation of the U.S. Air Force on Sept. 18, the history of U.S. military aviation can be traced back to 1907, when the U.S. Army created the Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps.

World War I and between wars

In 1917, upon the United States’ entry into World War I, the first major U.S. aviation combat force was created when an Air Service was formed as part of the American Expeditionary Force. Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick commanded the Air Service of the AEF; his deputy was Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell.

These aviation units, some of which were trained in France, provided tactical support for the U.S. Army, especially during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne offensives.

Concurrent with the creation of this combat force, the U.S. Army’s aviation establishment in the United States was removed from control of the Signal Corps and placed directly under the United States Secretary of War. An assistant secretary was created to direct the Army Air Service, which had dual responsibilities for development and procurement of aircraft, and raising and training of air units. With the end of the First World War, the AEF’s Air Service was dissolved and the Army Air Service

in the United States largely demobilized.

In 1920, the Air Service became a branch of the Army and in 1926 was renamed the Army Air Corps. During this period, the Air Corps began experimenting with new techniques, including air-to-air refueling and the development of the B-9 and the Martin B-10, the first all-metal monoplane bombers, and new fighters.

Technology

During World War I, aviation technology developed rapidly; however, the Army’s reluctance to use the new technology began to make airmen think that as long as the Army controlled aviation, development would be stunted and a potentially valuable force neglected.

Air Corps senior officer Billy Mitchell began to campaign for Air Corps independence. But his campaign offended many and resulted in a court martial in 1925 that effectively ended his career. His followers, including future aviation leaders “Hap” Arnold and Carl Spaatz, saw the lack of public, congressional, and military support that Mitchell received and decided that America was not ready for an independent air force. Under the leadership of its chief of staff Mason Patrick and, later, Arnold, the Air Corps waited until the time to fight for independence arose again.

World War II

The Air Force came of age in World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt took the lead, calling for a vastly enlarged air force based on long-range strategic bombing. Organizationally it became largely independent in 1941, when the Army Air Corps became a part of the new U.S. Army Air Forces, and the GHQ Air Force was redesignated the subordinate Combat Command.

In the major reorganization of the Army by War Department Circular 59, effective March 9, 1942, the newly created Army Air Forces gained equal voice with the Army and Navy on the Joint Chiefs of Staff and complete autonomy from the Army Ground Forces and the Services of Supply.

The reorganization also eliminated both Combat Command and the Air Corps as organizations in favor of a streamlined system of commands and numbered air forces for decentralized management of the burgeoning Army Air Forces.

The reorganization merged all aviation elements of the former air arm into the Army Air Forces.

Although the Air Corps still legally existed as an Army branch, the position and Office of the Chief of the Air Corps was dissolved. However, people in and out of AAF who remembered the prewar designation often used the term “Air Corps” informally, as did the media.

Maj. Gen. Carl A. Spaatz took command of the Eighth Air Force in London in 1942; with Brig. Gen. Ira Eaker as second in command, he supervised the strategic bombing campaign.

In late 1943, Spaatz was made commander of the new U.S. Strategic Air Forces, reporting directly to the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

Spaatz began daylight bombing operations using the prewar doctrine of flying bombers in close formations, relying on their combined defensive firepower for protection from attacking enemy aircraft rather than supporting fighter escorts. The doctrine proved flawed when deep-penetration missions beyond the range of escort fighters were attempted, because German fighter planes overwhelmed U.S. formations, shooting down bombers in excess of “acceptable” loss rates, especially in combination with the vast number of flak anti-aircraft batteries defending Germany’s major targets. American fliers took heavy casualties during raids on the oil refineries of Ploesti, Romania, and the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt and Regensburg, Germany, and it was the loss rate in crews and not materiel that brought about a pullback from the strategic offensive in the autumn of 1943.

The Eighth Air Force had attempted to use both the P-47 and P-38 as escorts, but while the Thunderbolt was a capable dog-fighter it lacked the range, even with the addition of drop tanks to extend its range and the Lightning proved mechanically unreliable in the frigid altitudes at which the missions were fought.

Bomber protection was greatly improved after the introduction of North American P-51 Mustang fighters in Europe. With its built-in extended range and competitive or superior performance characteristics in comparison to all existing German piston-engined fighters, the Mustang was an immediately available solution to the crisis.

In January 1944, the Eighth Air Force obtained priority in equipping its groups so that ultimately 14 of its 15 groups fielded Mustangs. P-51 escorts began operations in February 1944 and increased their numbers rapidly, so that the Luftwaffe suffered increasing fighter losses in aerial engagements beginning with Big Week in early 1944. Allied fighters were also granted free rein in attacking German fighter airfields, both in pre-planned missions and while returning to base from escort duties, and the major Luftwaffe threat against Allied bombers was severely diminished by D-Day.

In the Pacific Theater of Operations, the AAF provided major tactical support under Gen. George Kenney to Douglas MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific Theater.

Kenney’s pilots invented the skip-bombing technique against Japanese ships. Kenney’s forces claimed destruction of 11,900 Japanese planes and 1.7 million tons of shipping.

The first development and sustained implementation of airlift by American air forces occurred between May 1942 and November 1945 as hundreds of transports flew more than half a million tons of supplies from India to China over the Hump.

The AAF created the 20th Air Force to employ long-range B-29 Superfortress bombers in strategic attacks on Japanese cities.

The use of forward bases in China (needed to be able to reach Japan by the heavily laden B-29s) was ineffective because of the difficulty in logistically supporting the bases entirely by air from its main bases in India, and because of a persistent threat against the Chinese airfields by the Japanese army.

After the Mariana Islands were captured in mid-1944, providing locations for air bases that could be supplied by sea, Arnold moved all B-29 operations there by April 1945 and made Gen. Curtis LeMay his bomber commander, reporting directly to Arnold.

LeMay reasoned that the Japanese economy, much of which was cottage industry in dense urban areas where manufacturing and assembly plants were also located, was particularly vulnerable to area attack and abandoned inefficient high-altitude precision bombing in favor of low-level incendiary bombings aimed at destroying large urban areas.

On the night of March 9–10, 1945, the bombing of Tokyo and the resulting conflagration resulted in the death of more than 100,000 persons. About 350,000 people died in 66 other Japanese cities as a result of this shift to incendiary bombing. At the same time, the B-29 was also employed in widespread mining of Japanese harbors and sea lanes.

In early August 1945, the 20th Air Force conducted atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in response to Japan’s rejection of the Potsdam Declaration which outlined the terms of surrender for Japan.

Both cities were destroyed with enormous loss of life and psychological shock. On Aug. 15, Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan, stating:

“Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should We continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects; or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.”