The summer of 1967 can be remembered as a time of profound change. Many cities in America were aflame, the airwaves were full of music that a few years earlier wasn’t thought of, and the Vietnam War was raging a world away.

In a small town that summer — Blanchard, Washington — 18-year-old Jerry Prentice was drafted by the Army and responded by giving his country an effort beyond the call of duty. He was following in the footsteps of his father and uncle who both served in World War II. His uncle was awarded the Bronze Star in the 1980s.

While today we think of many 18-year-olds having as their biggest worry whether they should go to college or get a job, a young Jerry Prentice, as well as thousands of other Vietnam veterans, faced life and death decisions and peril minute by minute.

He did his basic training a short distance from his home at Fort Lewis, Washington, and then it was on to Fort Eustis, Virginia, for advanced infantry training in sheet metal repair.

After finishing his AIT, he took leave and then left for Phu Loi Base Camp, South Vietnam, which was north of Saigon near the Cambodian border.

He arrived in Vietnam, Jan. 12, 1968, and didn’t have a minute to settle in as the Tet Offensive was beginning. It was the largest military operation up to that point of the war, as every city and military base in South Vietnam was attacked.

The next three months would be harrowing and downright scary.

“I was trained as a sheet metal repairman, but when I was needed, I went with the Chinook helicopter crew as a door gunner,” Prentice said. “We lived in a bunker to avoid the constant rockets and mortars. The Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was the main supply line for the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, was very close to where we were located.”

In January 1969, it was time for Prentice to go home on leave. When he arrived at the Seattle airport, it was not a welcoming homecoming.

“I was in uniform and there were a number of groups protesting,” he said. “I was called all kinds of names, none of them nice, so I ducked into a restroom to change into civilian clothes. It was surprising and disappointing to see this reaction.”

His next assignment was an 18-month tour at Fort Benning, Georgia, working on airplanes and helicopters.

Political figures and high-ranking military officers used many of the aircraft there.

However, a temporary duty assignment at Homestead AFB, Florida, brought him close to the Cold War.

“A Cuban pilot landed at the base flying a Soviet MiG,” he said. “I had never seen a MiG. The aircraft was covered with a tarp, and the base was shut down.”

When his Army tour completed, Prentice began a long journey, which included a variety of jobs, and resulted in him discovering himself and coming to grips with his demons.

Prentice tried his hand at halibut and salmon commercial fishing off the coast of Alaska, and had a short stint at Boeing, but he said he got tired of the rain and took a job with TIMEC of Texas working on oil refineries, a job he stayed with for almost three decades.

In 2008, Veterans Affairs granted him a 100-percent disability. Agent Orange had been dropped in the area where he had worked in Vietnam, so he was medically retired. He has suffered through five strokes and total bypass surgery since he left the Army, as well as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Prentice said he had blotted out most of what had gone on in his life for six years after leaving the Army. His salvation began with a series of events, the first being when his wife, Shelley got in touch with the Combat Veterans Motorcycle Association.

They are a group of combat veterans who ride motorcycles with their principle mission to give back to other veterans by welcoming them home and offering whatever assistance they need, she said. They have chapters all over the world, with more than 18,000 members.

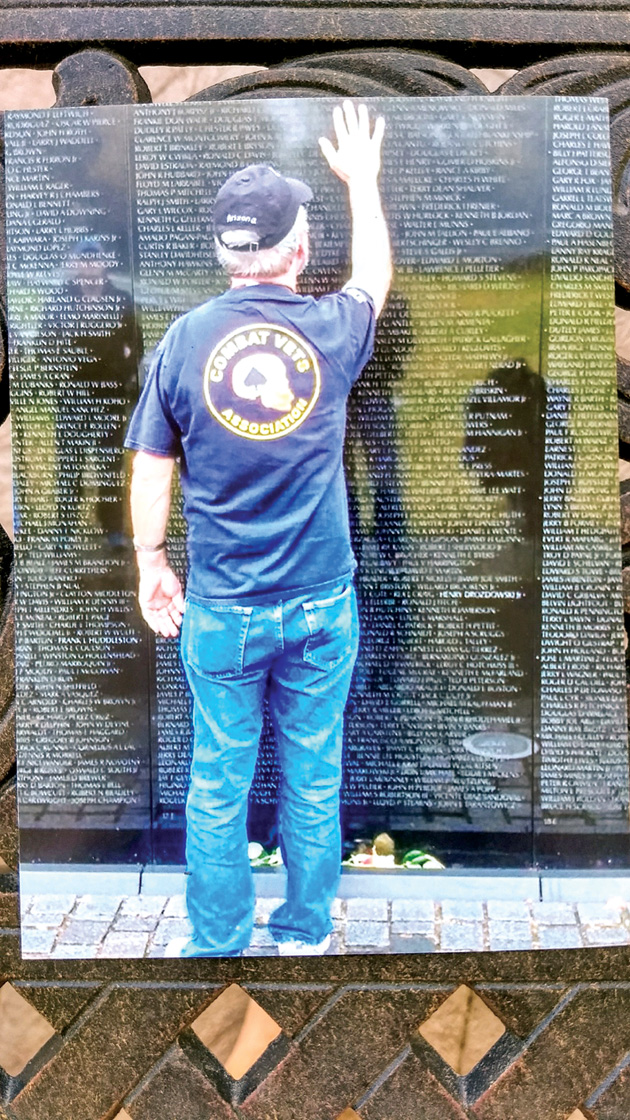

Another aspect of Prentice’s recovery was the Traveling Wall. While the main stationary wall is located in Washington, D.C., there are traveling walls that go to various locations in the country. The traveling wall began the real healing process.

He said he spent five years with the traveling wall before embarking to Washington to visit the main wall in 2009.

“The traveling wall may have saved my life,” he said.

More than that, Prentice has high praise for Operation Freedom Bird, a group that has been helping veterans come to grips with their past.

“I visited Washington for four days and went through intense counseling,” he said.

Prentice has the highest praise for his wife as an enormous help in his recovery, but he also credits his service dog, Emma.

“The dog and I went through intense training,” he said. “My first dog died at 15, so it is great to have Emma. I am grateful to the Combat Veterans Motorcycle Association for their $11,000 donation to train vets and their dogs. The training is a six-to-nine-month commitment, and most of the dogs are rescue dogs.”

At this point in Prentice life, he said his mission in life is to be there for other vets in any way he can, so they don’t have to go through what many Vietnam veterans went through when they returned home.

Prentice, in a recent interview on ABC 15 Sonoran Living, offered these thoughts.

“My country needed me, and I went,” he said. “Why did I make it back, and he didn’t? Why is his name on the wall and mine isn’t? People go to war too young. You are never relieved of your oath of duty. I have not done my duty, yet.”

Editor’s note: Prentice’s interview can be accessed on YouTube by entering Sanderson Ford & ABC15 salute combat veteran Jerry Prentice.

Jerry Prentice in front of the Vietnam War Memorial Moving Wall.