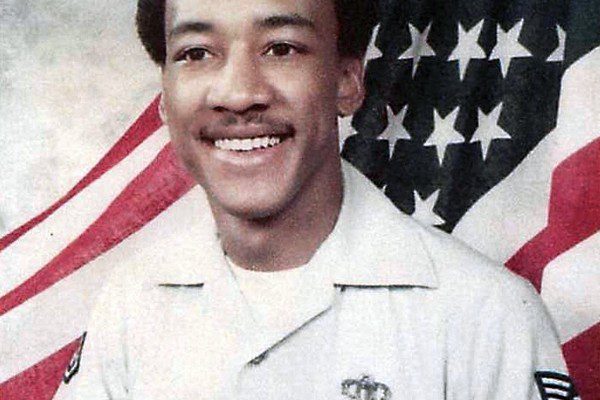

“Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get,” said Bernard Bruce, retired 56th Fighter Wing Occupational Safety and Health manager.

While quoting the famous Forrest Gump line, Bruce reflected on his more than 50 years of service to the Air Force and laughed at his original plans for his life’s trajectory.

Bruce grew up in Wilmington, Del., in the 1950s and 1960s in a diverse city that had a small town feel to it. Raised by his grandparents while his father was in the Air Force, he learned lessons each evening at the dinner table from the Bible, Boy Scouts handbook and Good Citizens guide. He attended school during the Cold War and he remembers diving under desks for protection from the incredible power of an atomic bomb.

As he approached adulthood, the Vietnam War began. Bruce said he recalled hearing Martin Luther King Jr. voice his opposition for the conflict in his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam.” Bruce said while MLK’s words impacted him, civil rights leader Malcom X’s vision resonated even more. Had it not been for the draft notice that arrived, Bruce presumed that he would have been a black panther.

“They say the journey of a thousand steps begins with a single step,” said Bruce. “In my case it was four; the four steps off a bus that arrived at Lackland Air Force Base, (Texas). I stepped off that bus into a totally different world.”

In June 1969, Bruce dove into an expedited Basic Military Training as the Air Force accelerated people through training to sustain the war effort.

“I picked pharmacy technician,” said Bruce. “If I ended up going to Vietnam I’m going to be in a hospital with a big red cross, and they’re not going to hurt me.”

“I get these orders on the 28th day (of BMT),” Bruce continued. “I get really pissed and I’m stomping around. Of course that draws my (training instructor)’s attention who immediately wanted to know what my problem was. I said, ‘sir these orders are wrong, I am supposed to be a pharmacist, they want me to be an air traffic controller.’”

In a stern voice Bruce’s TI told him to get behind the barracks. In 1969 an Air Force trainee knew that meant “hands on” training.

“My TI was a pretty big man, he was a black guy,” said Bruce. “Something really interesting happened: the expression on his face changed; it was like I was speaking to my uncle or maybe my dad. He said, ‘most blacks in the United States Air Force today work in supply, in the dining facility, as civil engineers. They do a lot of physical stuff, they don’t get an opportunity to go into operations like this. This is a really good job. You’re very articulate. If you pull your head out of your butt you would be a pretty good Airman. Now, stop whining, take these orders and get back in formation.’ And the TI face came back.”

On that day, his course changed again. After BMT, Bruce went to Keesler AFB, Miss., to receive his ATC technical training.

Bruce explained he joined a career field that, at the time, women were not allowed in and he was the only black ATC Airman.

After training, Bruce was assigned to Ellington AFB, Texas, where the NASA program was. About nine months after Apollo 11, Bruce recalled that a major from public affairs entered the tower with Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon. Armstrong introduced himself to each person in the tower and answered their questions. Finally, he approached young Airman Bruce. After brief introductions, Bruce asked Armstrong how much money he made on his historic space flight.

“[Armstrong] said ‘first of all I didn’t make a lot of money,’ and I have no filter, I said ‘you got a lot of money, you just don’t want to tell me how much money you made,’” said Bruce. “My supervisor steps in and he says ‘Bruce knock it off.’ At that moment the major said ‘we got to go,’ and pulled Mr. Armstrong over to the door, he waved and went out.”

Bruce said his supervisor was livid and counseled him. However, a couple days later, Armstrong returned to speak with Bruce. Bruce proceeded to unload apologies for his behavior and after he was done, Armstrong spoke.

“He said ‘actually it was a good question,’ and hands me a piece of paper,” said Bruce.

In his hands was a government travel voucher that laid out Armstrong’s entire trip and all the expenses covered. The voucher listed all the locations he traveled to: from his home to Cape Kennedy; Cape Kennedy to the moon; the moon to the Indian Ocean, where he was picked up by a helicopter, put on a military aircraft carrier and flown back to Hawaii; then to the NASA Johnson Space Center to Cape Kennedy; and, finally home. On the Apollo spacecraft, NASA provided Armstrong quarters and meals. The government covered each expense throughout the trip. On the backside of the voucher it stated, total reimbursement: $49.10.

“Neil Armstrong made less than $50 traveling to the moon,” said Bruce. “I thought the man made hundreds of thousands of dollars. Up until last Saturday, a copy of that travel voucher was on my desk. It taught me never to assume anything, always check your facts before you make a decision.”

His next several assignment were to Southeast Asia: the Vietnam War. Over five years, Bruce was stationed in Thailand, Vietnam, Korea and the Philippines. As an ATC, he guided pilots through tumultuous conditions, occasionally holding their fate in his hands.

“The biggest test I had was the years in Southeast Asia, because 20 guys go out, but out of the 20 maybe 16 come back, and of the 16, four or five have battle damage and they really want to land,” said Bruce. “The problem is if you put that guy down on the runway and he crashes the other people can’t land, so we normally have to hold those guys out and bring the good birds in first. It’s a pretty tough call to make.”

In those years, the stressors of the combat environment increased the already high-level of job-related stress of an ATC who makes dozens of rapid decisions in a short period of time and with no margin for error.

“On one occasion I recovered 22 airplanes in about 40 minutes,” said Bruce. “As I started the recovery operation, the radar goes out. I can’t see anything and now, based on where I saw them, I had to put them into holding patterns, separated by airspeed and altitude bringing them in on instrument approaches.”

Bruce successfully landed all 22 of the aircraft. Years later as an instructor, he shared his story and realized nobody had ever completed an operation. Bruce said that before his emergency experience, landing aircraft without RADAR as a guide was only taught as theory.

After his time as an ATC, he became a radio DJ for Armed Forces Radio and Television hosting the “Sound of Unlimited Love,” or SOUL, for a couple years. Eventually he returned to the U.S. to retrain into the safety career field and became the safety superintendent at Lackland AFB. As he returned to the base where he stumbled through BMT two decades earlier, Bruce realized he already had an intimate connection with his new office.

“I look at this building, it’s the 37th Training Wing safety office, and I keep looking at it and all of a sudden it dawns on me what that building is,” said Bruce. “It’s a World War II style barracks, my original basic training barracks from 23 years ago. I go in and the secretary says ‘that is going to be your office over there’. I look and my MTI’s bunkroom is now my office. I cannot believe this. It is absolutely amazing. I end and begin my career in the same building.”

Bruce stayed at Lackland for three years and retired with a parade that outshined any retirement he could have imagined. After a year hiatus, he returned to the Air Force by accepting a position at Holloman AFB, N.M., and then Luke AFB to work in the safety office, where he worked for the next 24 years.

“Every day is a new day for us,” said Bruce. “Our job is to keep people from getting hurt, equipment from being damaged and to keep the mission moving forward. You never know how it’s going to work out on a daily basis but it’s a lot of fun, it’s very rewarding and very challenging.”

As the Occupational Safety and Health manager at Luke, Bruce interacted with many Airmen and was very involved in base operations. After a while, he noticed that people recognized him and referred to him as the “Safety Dude.”

“I did everything to reject the call-sign,” said Bruce. “People would say, because they remembered me from safety training, ‘Aren’t you the safety dude?’”

He gave up fighting the name and even embraced it by sporting a “Safety Dude” hat and displaying the distinction on his name tag. Safety Dude has been making his mark on Luke for over 20 years.

“I was a member of Mr. Bruce’s team for more than 11 years,” said Jason De Jesus, 944th Fighter Wing Weapons Safety manager. “I had the pleasure of being trained/mentored by him as a young enlisted safety professional for five years, before becoming his number two for another six years when I transitioned from Active Duty to the Air Force Reserve and joined civil service.”

“He has imparted enlisted heritage to generations of Thunderbolts, helping bring our history to life and making us even more proud to serve,” De Jesus continued. “He helped us understand how far we have come as a diverse Air Force by sharing the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen and his personnel experiences as a black man growing up in the Air Force. As the ‘Safety Dude’ he has saved countless members of the Air Force by teaching them what not to do without causing them to become risk adverse.”

After more than 50 years, Bruce has experienced dozens of uniform changes, with each change the garb became more realistic and refined. He observed the culture and leadership changed in the same way. Bruce said the Air Force he joined in 1969 is vastly different from the one he leaves in 2021.

He explained the biggest changes he noticed have been professional development and promotion opportunities. Additionally, the Air Force evolved to realize that it enlists Airmen but re-enlists families, therein changing to prioritize and commit to military families’ wellbeing.

Moreover, he noticed the push to become a more accepting Air Force that embraces diversity and inclusion. Today Bruce leaves an Air Force that aligns with the values that he and the military share.

“Once I understand your story, I understand what you go through, not what I perceive you to go through,” said Bruce. “That’s your reality. My reality is totally different, but my reality doesn’t negate yours. If you’re going to help someone, you have to take action to help them. It’s not saying ‘I’m colorblind’ or ‘I don’t have anything against gay community.’ If you’re not working to actively support them, you’re hurting them.”

As he leaves his role in the Luke safety office, he is hopeful towards his future and intent on staying busy. He plans on building his family genealogy knowledge, spending time with his kids and wife of 47 years, continuing to participate as a historian in the local Tuskegee Airman chapter and eventually writing a book, bringing the stories of the Air Force to the forefront. As for what he leaves behind, Bruce is hopeful the Air Force will only continue to improve.

“I would be very disturbed and upset to end my career if it wasn’t for the people that come behind me,” said Bruce. “There are young people out there who are ready to stand up and lead the charge. Leaving after 50 years, I’ve seen (the Air Force) improve tremendously. My faith is in the people that come behind me. It’s their Air Force and I think I’m leaving it in competent hands.”

As Bruce turned off his office lights and closed the door for the last time, he reflected how his life has seemingly paralleled that of Forrest Gump. Bruce lived through the Civil Rights movement, he met Neil Armstrong, and as an ATC Airman watched Richard Nixon fly across the United States in Air Force One as Gerald Ford swore in as president.

“All the things I did were just right, just perfect, whether it’s a success or failure because it created who I am today,” said Bruce. “I’ve benefited from the Air Force because it was the organization I needed at the exact moment in mind. I don’t regret that 50 years of experience and that’s a good way to go.