Many of the service members who gave their lives in service to our country barely had a chance to begin their own.

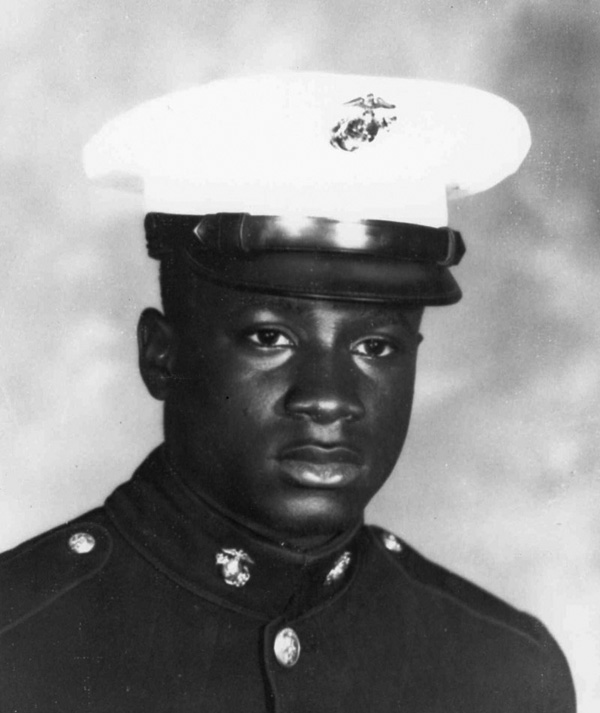

Marine Corps Private 1st Class Robert Jenkins Jr. falls into that category. What he lacked in age, he more than made up for in courage, commitment and dedication. For that, he earned the Medal of Honor.

Jenkins was born June 1, 1948, in Interlachen, Fla., just east of Gainesville. He had a brother and three sisters and graduated from Palatka Central Academy, an all-Black high school, in 1967.

Jenkins’ family and friends said he was a nice teen who got good grades, had a lot of friends and worked hard for his family, according to the Florida Department of Military Affairs. He had a talent for masonry and woodworking, but he was also looking forward to a career in the Marine Corps. His mother said during a 1996 Tampa Tribune interview that he wanted to volunteer instead of being drafted.

Jenkins enlisted on Feb. 2, 1968, as the war in Vietnam was raging. Within five months, he was deployed to the Southeast Asian country. Attached to the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, Jenkins initially served as a scout and driver.

During the several months that he was in Vietnam, a lot of defensive battles broke out for control of U.S. Marine fire control support bases on or near the demilitarized zone, which split the north from the south. So, he was eventually assigned as a machine gunner with the battalion’s Company C.

Early on the morning of March 5, 1969, Jenkins’ 12-man reconnaissance team was prepared to defend Fire Support Base Argonne, just south of the DMZ, from an impending attack. When it came, a North Vietnamese Army platoon started bombarding them with fire from automatic weapons, mortars and grenades.

Jenkins and another private first class, Fred Ostrom, were fighting off the enemy together in a ditch when a North Vietnamese soldier threw a hand grenade at them. Jenkins immediately pushed Ostrom to the ground and jumped on top of him to shield him from the blast.

Ostrom survived. Jenkins did not. He was a few months shy of his 21st birthday.

“He saved more than my life — I have two kids,” Ostrom said in a November 1996 interview with the Tampa Tribune.

U.S. helicopters eventually arrived at the scene to keep the North Vietnamese at bay long enough for the Marines to be airlifted out. Two other men in Jenkins’ units were killed in the firefight. Six were wounded, including Ostrom.

Ostrom said that, while he only knew Jenkins for a few months, the young Marine left an indelible mark on his life.

“He was someone I could trust, someone I could count on,” Ostrom told the Tampa Tribune. “What happened was in Robert’s character. If it hadn’t been me, it would have been someone else [he saved]. I am proud of him and I miss him.”

The valor, courage and selflessness it requires to give your life for another was not overlooked the day of his death. Jenkins received a posthumous recommendation for the Medal of Honor. On April 20, 1970, his family accepted it on his behalf from Vice President Spiro Agnew during a White House ceremony.

When Jenkins’ body was returned home, his family decided that he would be buried in Sister Spring Baptist Cemetery in his hometown.

In the decades since Jenkins’ death, Interlachen has made a concerted effort to remember his sacrifices. Jenkins’ high school was integrated in the 1970s and has since been renamed Robert Jenkins Middle School. The Robert H. Jenkins Jr. Memorial Park was built during the same decade, and a post office was eventually named in his honor.

But the biggest tribute may have been from Ostrom, the man Jenkins saved. When Ostrom first visited Jenkins’ grave in 1995, he told the Tampa Bay Times that the plot was in disarray and not befitting a hero. So, he spent a year working with veterans’ organizations and Jenkins’ family to get it cleaned up. By Veterans Day of 1996, a rededication ceremony was held for Jenkins, complete with a Medal of Honor headstone and a footstone donated by several veterans’ groups.