“I want to tell you what the opening of the second front in this sector entailed, so that you can know and appreciate and forever be humbly grateful to those both dead and alive who did it for you.”

– Ernie Pyle, World War II combat correspondent, June 1944

LANCASTER, Calif.–Seated in my office at High Desert Medical Group on June 6, 73-years after D-Day, Henry Ochsner hardly looked to be 94. He could pass for a kid of 80 years.

On June 6, 1944, 73 years ago, Henry was busy as could be, preparing to deploy with the 101st Airborne Division.

He wears a black baseball cap that tells part of his story: “World War II Veteran — Screaming Eagles.”

On June 6 it was a long time from darkness until dawn. At dawn, it got loud.

If you were up on the bluffs and hedgerow fields of the Normandy coastal area, you could hear the big guns of the U.S. and Royal navies, pouring battery fire to give cover to the troops wading ashore at Omaha and Utah beaches, for the British and Canadians, at Juno, Gold and Sword beaches.

Thousands of paratroopers survived the jump, and the controlled crashes of gliders descending on the French farming country. Henry and the 321st Glider Artillery would join them the following day as part of an organic artillery component that supported the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The glider artillery battalion he served with would follow the 506th PIR and its famed Easy Co. known as the “Band of Brothers” all the way from Normandy, through Holland and the siege of Bastogne, to the capture of Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest” alpine redoubt at the end of the war, according to the official history of the 101st Airborne Division.

World War II veterans are leaving the world stage at a continuously accelerating rate that in recent years. The Department of Veterans Affairs estimates about 1,000 a day. Surely, it is more daily, as even the youngest World War II veterans have pushed past their 90th birthdays.

But 90 isn’t what it used to be. Good genetics, good care, taking it easy. At Christmas my Vietnam veteran buddy Michael Bertell and I joined in a 100th birthday celebration for Felix Jamison, who was not at D-Day. He was with MacArthur in the Philippines, and he is still here.

Instead, Felix, the master sergeant of an all African-American quartermaster company rolled ashore with Gen. Douglas MacArthur when the American caeser made good on his promise, “I shall return.”

So, we still have a few World War II veterans among us, and we must treasure the time spent among them.

On this 73rd anniversary of D-Day, before meeting with Henry, I headed over for the weekly Coffee4Veterans hosted at Crazy Otto’s restaurant on Avenue I in Lancaster. I sat in a booth for coffee with Art Ray and his bride of many years, Debbie. They are there most Tuesdays.

I knew Art had served on a battle cruiser during World War II, and tried to remember the name. Battleships are named for states, the USS Iowa. Cruisers are named for cities.

“It was the USS Quincy, and it was a good ship,” Art said. “We were there at D-Day.”

Art was there. And pushing past his 90th birthday, he is here, too.

The USS Quincy was part of an armada of 5,000 ships that sailed from England in heavy chop, catching up with the more than 13,000 aircraft that dropped Allied paratroopers and strafed and bombed enemy positions.

Those thousands of ships were seen through field glasses on the horizon line by thousands of defenders of Adolf Hitler’s forces of the Third Reich.

“We were firing six-inch and eight-inch guns,” Art Ray recalled. “There was a lot of noise.”

During the period June 6 through 17, in conjunction with shore fire control parties and aircraft spotters, Quincy conducted highly accurate pinpoint firing against enemy mobile batteries and concentrations of tanks, trucks, and troops, according to the Dictionary of American Naval Vessels.

The rounds were cascading onto the bluffs above the landing beaches, trying to chip away at the bunkers and Nazi artillery, trying dislodge the enemy from their machine guns and barbed-wire fortifications while Americans, British and Canadian troops waded ashore under heavy fire.

More than 9,000 Allied troops were killed or wounded in that single, longest of long days. They might have foundered in the water, but ultimately, the Allied troops fought their way off the beaches, and up the cliffs and bluffs, and into the hedgerow farm country of coastal France.

While the men were coming from the sea, Henry Ochsner was with his brother grunts from the 101st Airborne Division and their first cousins over in the 82nd Airborne “All American” Division. They were heading in from flooded landing fields and hedgerows to meet up with the troops fighting their way up from the beaches.

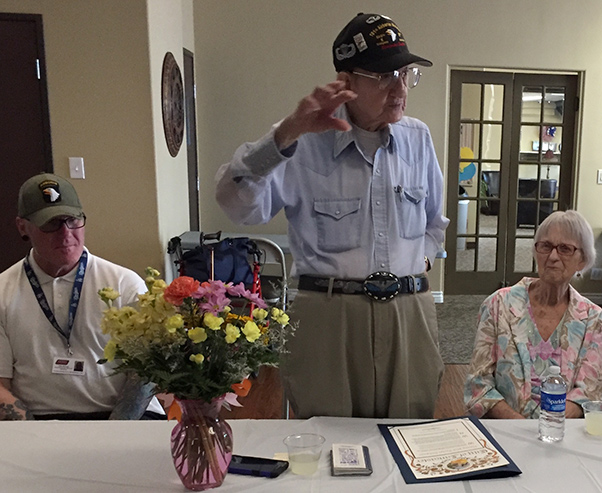

Henry Ochsner describes the fighting in Normandy that started on D-Day… with bride of 70 years, Violet, and Nathan Burnett, a Cold War veteran of Henry’s outfit, the 101st Airborne.

Henry Ochsner describes D-Day … with bride of 70 years, Violet, and Nathan Burnett, a Cold War veteran of Henry’s outfit, the 101st Airborne.

The 101st and 82nd Airborne units had been scattered all over the countryside, few landing anywhere near their designated rally points. But they rallied anyway, and sewed chaos in the Nazi rear and forward areas.

Another D-Day veteran who resides in the Antelope Valley is John Humphrey, a D-Day paratrooper with the 82nd, who went missing behind enemy lines for more than a week, but when he turned up, he had scouted vital information on enemy gun positions.

Altogether, more than 156,000 Allied troops participated in the Liberation of Europe that began on D-Day. Art Ray and Henry Ochsner lived to tell, lived to return home to rebuild their lives in the America we now know.

Thanks to historians and authors like Ambrose and Tom Brokaw, they have become known as “The Greatest Generation.”

But this was not Henry and Art’s only entry into the history books.

As crew on the USS Quincy, Art served on the ship that carried President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the Yalta Conference with Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin. The Quincy delivered FDR to the Mediterranean island of Malta, whereupon he proceeded by air to Crimea, and Yalta to negotiate the shape of the post-war world.

Henry survived the siege of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge launched in December 1944.

The battle in the Ardennes Forest of Belgium and France was Hitler’s last desperate attempt to throw the Allied forces back to the sea. At Bastogne, in Europe’s coldest winter in a half century, the 101st Airborne was surrounded, and battered, but never beaten. Brig. Gen. Anthony MacAuliffe’s response to a German army demand for surrender was one word – “Nuts.” The 101st Airborne hung on until relieved by George Patton’s 3rd Army.

“I was a Jeep driver, and I was trying to get the Jeep started in 13 degrees below, and it just kept going ‘uh-uh-uh,’” Henry recalled. “A buddy of mine shouted ‘We got one coming in,’ and it was an 88 millimeter shell. I dived to the basement where we spend the night before, and my Jeep was destroyed, just a twisted mess. I got a shrapnel splinter through my boot in my heel, and I fixed it with a Band-Aid.

“They told me if a medic had put the Band-Aid on, I’d have gotten a Purple Heart, but I put it on, so that’s how I lost my chance for Purple Heart.”

With 321st Glider supporting 506th PIR,” Henry fought all the way to Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s mountaintop resort redoubt, the “Eagle’s Nest.”

My employer, High Desert medical Group, hosted a small reception for Henry, and Violet, his bride of 70 years. The couple had recently rededicated their marriage vows.

Cake and punch was served. Lancaster City Manager Mark Bozigian – on behalf of Mayor R. Rex Parris and the City Council – presented an honorary scroll recognizing Henry and Violet, their long marriage, and Ochsner’s distinguished service during World War II.

“I don’t really feel worthy enough to address you, but I do want to say how grateful I am for what you did in World War II,” Bozigian said. “Your generation, and I really do believe it, was our most important generation. You literally saved the world.”

Henry and Art were among the fortunate who returned home from the landing fields and war-tossed sea.

When Henry first laid eyes on Violet, she was working as a waitress at a diner in Seattle. He persuaded his sister, a co-worker, to persuade Violet to go out with him on a date. On the way to the dance, Henry’s sister sat in between Henry, who was at the wheel of a roadster, and Violet, who was still making up her mind about the young war veteran.

It was to a dance, in a kind of big barn-like dance hall. They have been together ever since.

At the reception, Henry said, “I just want to thank all of you for thinking of us, and yes, as of March 6, it was 70 years and we are happily married.”

The couple raised three daughters. Henry did a stint in the Merchant Marines, and drove an extraordinary number of miles as a truck driver without ever having an accident.

“When I look at him, I see the kindness in his eyes, and it’s like when we first met,” Violet said. “He has always been that man. He is the same man now.”