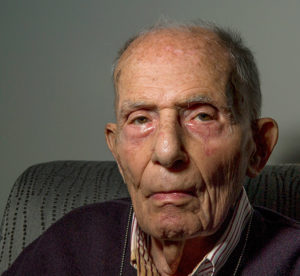

Bob Behr, 94, experienced the entire Holocaust from 1933 until he was liberated in 1945. Behr would eventually immigrate to the U.S., where he enlisted in the Army, and later worked for the Air Force as a civilian in the intelligence field for more than 35 years.

Fear. In one word, Bob Behr used fear to describe how he and most of the Jewish community in Germany lived their lives from 1933 until the mid-1940s. In that time, Behr would suffer persecution, work in forced labor, be arrested and sent to the Theresienstadt “camp-ghetto” with his family, and ultimately, survive the Holocaust.

Following his liberation in 1945, Behr would eventually find his way to the U.S., where he enlisted in the Army, and nearly five years later was discharged and worked for the Air Force as a civil servant in the intelligence field for 35-plus years.

Before 1933, when Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Behr and his family, who were very pro-German, lived a normal middle-class life. His father was a doctor who served Germany during World War I, and his mother stayed home to raise Behr, their only child.

“I just grew up like a normal kid,” said Behr, who is now 94 years old. “We went on vacation. We went to the sea in the summer time.”

Behr said he first became conscious that something was wrong when he was about 8 years old. His father was politically savvy and very interested in the political future of Germany, so the radio in their house was always playing.

“I heard things coming out of the loud speaker … which I didn’t understand, but they bothered me,” Behr recalled.

The radio commentator would constantly talk about the Jews.

“Jews were responsible for the Versailles Treaty; Jews were (the) reason Germany lost the war. I didn’t understand most of it,” Behr said. “All I knew is that the content of the speech was anti-Jewish.”

In January 1933, when Hitler came into power, the Berlin and Germany Behr once knew ceased to exist.

“When Hitler was appointed the chancellor of Germany, life changed so drastically,” he said. It was an immediate change. The radio broadcasts Behr remembered listening to were building blocks for what would become an anti-Semitic German society.

Bob Behr in his Army uniform. Following his liberation in 1945, Behr, a Holocaust survivor, would eventually immigrate to the U.S., where he enlisted in the Army, and later worked for the Air Force as a civilian in the intelligence field for more than 35 years.

The Nazi party immediately instituted and enforced laws that persecuted Jews.

“My father, a doctor, was not allowed to call himself doctor,” Behr said. “He was a medical expert, the word doctor was prohibited.”

The laws also prohibited Jews from having cars, telephones and pets; they couldn’t use public transportation or buy newspapers, and the list went on from there.

According to Behr, the Star of David wasn’t required for identification until September 1940.

“Before that, no one knew,” he said. “But being … German Jews, being raised in a society which, quote, abides the law, unquote — Jews were afraid. No one knew that I was Jewish by walking down the street.

The fear of being beaten, shot or thrown into concentration camp was enough to scare Jews into abiding by the discriminatory laws.

“It was a life which was dominated by fear,” Behr said.

Behr was also kicked out of school in 1934, because Jewish children were only able to attend Jewish-run schools.

For about six months in 1936, he attended boarding school for Jewish children in Lund, Switzerland.

During his time away, the Germans had established forced labor, which awaited Behr upon his return.

“(It was) different from slave labor, forced labor I (could live at my) home, but what forced labor meant that you had to report to an office in Berlin every morning to get a job assignment,” Behr said.

Bob Behr, right, and another American Soldier pose outside of the German-American Youth Club in Germany. Following his liberation in 1945, Behr, a Holocaust survivor, would eventually immigrate to the U.S., where he enlisted in the Army, and later worked for the Air Force as a civilian in the intelligence field for more than 35 years.

Since Jews couldn’t have cars or use public transportation, Behr rode his bike daily to and from his job.

Most of the jobs Behr was assigned consisted of hard manual labor. A few jobs included him carrying coal to buildings that had central heating, and carrying bricks on construction sites.

Behr’s parents had divorced and he was living with his mother in November 1938, when his father was taken away, and Behr would never see him again.

Behr’s father was among more than 30,000 Jews arrested between Nov. 9 and 10, 1938, during a wave of anti-Jewish violence called Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass.” According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the pogroms — in retaliation for a German official’s shooting by a Polish Jew in Paris — took place throughout Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia recently occupied by German troops.

In 1942, the Gestapo had retrieved a postcard marked for Behr’s mother, revealing her assistance in helping a woman make her way to Switzerland. Behr, along with his mother and step-father, was arrested and sent to Theresienstadt “camp-ghetto” in Czechoslovakia.

Because Behr’s stepfather was a World War I veteran, who the Nazis had agreed not to kill, the family was sent to Theresienstadt, rather than to a killing center or concentration camp.

During a “First Person” interview with the museum in 2013, Behr said his first job was to bury the dead.

Behr said during the 2013 interview that “people died like flies from diseases, sanitation,” and when they died there was no viewing, or something appropriate.

“After you do this for a while instead of honoring the dead, respecting them, all you care are about how heavy they are and how high you have to throw them,” Behr continued during the same interview. “You know what that does to your soul, your equilibrium, what that does to you, your mental ability, when you become so raw, so disinterested from reality that you don’t even think about things like honoring a dead person?”

During his time at the camp, Behr also helped build a railroad that connected Theresienstadt to the nearest station, which was six miles away. As the camp became increasingly crowded, the Nazis began “resettling” some of the residents to Auschwitz, Dachau and other camps where prisoners were not likely to survive.

Eventually, plans were made to build an SS headquarters at a satellite camp in Wulkow, Germany, and 200 volunteers from Theresienstadt were selected to help build it.

When the SS asked for volunteers, “They added a sentence, and that sentence is why I’m sitting here today,” Behr said. “They added a sentence saying if you volunteer to go and build their headquarters we will not kill your folks.”

Determined to keep his mother and stepfather alive, Behr volunteered.

Behr returned to Theresienstadt in 1945, reunited with his family, and worked in the kitchen. He and his family were liberated in May 1945. Following his liberation, Behr worked in a U.S. Army kitchen in Germany. He then immigrated to the U.S. in 1947 and joined the Army. As a Soldier, he was sent back to Berlin to work with German youth activities (GYA).

“I was a big chief of GYA, and what that GYA was supposed to do is to educate the future German people about democracy and freedom,” Behr said. He left the Army in 1952 and began working as a civilian for the Air Force’s 7050th Air Intelligence Service Wing at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. However, he spent time traveling back and forth between Ohio and Germany.

During the 1950s, he spent time in Germany interrogating Germans who were released back to Germany after being captured by the Soviets and held in prisoner of war camps in Siberia. Since Behr was fluent in German, he assisted with the questioning, trying to piece together what life was like for the POWs and give insight as to what was going on in Siberia. The Air Force called the mission “Project Wringer.”

“The Air Force had a brainstorm. We don’t know beans about what is going on in Russia. We’re going to take all these German POWs who are now free back home and interrogate them,” Behr said.

Aside from working with POWs, Behr was also instrumental in operations pertaining to East Germany. “In those days, our big enemy was not Russia — it was but it wasn’t — our immediate enemy was East Germany,” he said. “They wanted people to deal with these East Germans who are fluent in German and that how I got (roped in).”

Behr currently resides in Washington, D.C. with his wife of 60-plus years. He volunteers at the Holocaust Memorial Museum on a weekly basis, reminding visitors of the atrocities that were committed during his time, in hopes of preventing anything like it in the future.