By Bob Alvis, special to Aerotech News

It’s pretty common around our desert home to see people come to a stop, bend their necks and look skyward as the sounds of aircraft herald their approach overhead.

They usually stand still and share thoughts with other bystanders about the spectacle filling the sky and the sound of an engine that gave them the first clue that something pretty cool was about to fly over.

“Bird watching” in the Antelope Valley is pretty unlike bird watching anywhere else in the United States! Over the years, it’s given spectators some pretty cool and interesting subject matter to partake in and share.

Case in point was a Douglas aircraft that was built to fill a Navy requirement for a turbo-prop attack aircraft to be flown off of aircraft carriers.

In the late 1940s/early 1950s, the sound of jet engines were becoming commonplace at Edwards Air Force Base — but the sound now being introduced to the base was that of a power plant which would have a mass of teething problems, but would later go on to power thousands of aircraft in the United States military aircraft inventory.

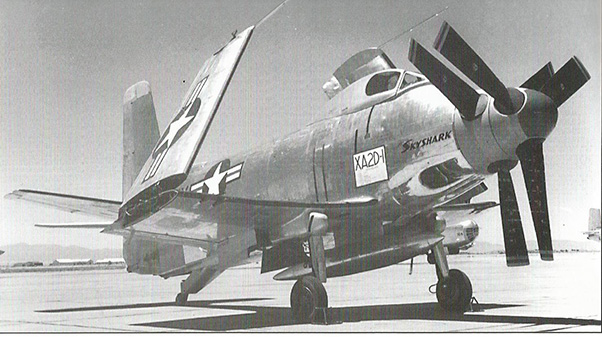

The Douglas A2D Skyshark was an impressive looking aircraft. Its large size with those two giant counter-rotating props made it look like a creature from a modern-day Transformer movie out of Hollywood, and just as scary! What really made it unique was that it was the first aircraft to incorporate a new engine design: the Allison XT40-A-2 turbo prop. It didn’t take long for the observer to see those two giant exhaust stacks on the rear fuselage to know that this baby meant business and was going to be loud!

The Skyshark required two engines that would produce an estimated 5,100 military and take-off horsepower, with 830 pounds of residual thrust at 13,620 rpm. The two engines were coupled together via a massive gearbox that would spin the giant propellers. The son of SPAD (the nickname of predecessor aircraft AD-1 Skyraider) was truly going to be one of a kind.

After many delays, the Skyshark finally arrived at Edwards for flight testing in the early months of 1950. When the Shark would fire up, ground personnel and everybody around the base knew it was running as the aircraft introduced a new sound to the constant whine of young jet engines. As a matter of fact, an indirect effect of the Skyshark’s power was soon noticed by personnel working around the aircraft, who found that ear plugs provided insufficient protection from the racket. Vibration from the operating engine introduced a “buzz” in their bones and joints that made it uncomfortable to remain in the area.

On May 26, 1950, George Jansen, a decorated World War II and Douglas test pilot, made the first flight that lasted two minutes and covered only five miles. The low vibration had him quickly shutting down the engines to prevent heavy engine damage, after a couple of flight inputs to check basic flight characteristics. On June 1 a 13-minute flight took place, followed by a 35-minute flight on June 2. There were so many squawks that the fourth flight did not take place until Oct. 18, when the flights finally became a bit more routine and averaged about an hour in length. By the Dec. 8, the prototype had made a total of 14 flights and had reached a top speed of 475 knots and an altitude of 27,000 feet. At this point there was enough data for the Navy to begin its preliminary evaluation of the Shark.

On Dec. 19, Navy pilot Lt. Cdr. Hugh Wood took the Skyshark up to perform some dive tests when ground crews on a mobile unit on the lakebed noticed a puff of smoke and vapor coming from the aircraft when the dive brake closed. The ground crew radioed Wood and asked if everything was OK and he replied in the affirmative. After a flyby on the lake bed for a visual inspection, gremlins started to make their presence known as the aircraft with gear down made a landing approach. Coming in at a high rate of speed and at a 30 degree angle, the aircraft struck the lakebed and was destroyed, taking the life of the pilot in the ensuing fire. It had made 23 flights and had accumulated 19.35 hours of flight time. It wasn’t until April 3, 1952, that the second prototype made its first flight, with George Jansen back at the controls.

Not long after, the Skyshark fell out of favor with the Navy, as the design and engines continued to be plagued with problems. The Navy turned their attention to the very capable A-4 Skyhawk to fill their requirement for a carrier-based attack aircraft. A total of 10 Skysharks were produced and flight tested at Douglas, which eventually transferred the flying examples to Allison where they were used to develop turboprop engines that would end up powering everything from Huey Helicopters to C-130 transports.

For a period of time the Skyshark was a fixture in the Antelope Valley skies. Its sound was one that always had people looking to the air as those big counter-rotating props and turbo engines would shake the spectator’s soul. It was a failure as an aircraft, but a success in the development of technology that would benefit aircraft of the future.

Today only one of these remains — it was last seen in 1996, sitting unassembled alongside a hanger in Idaho Falls. Its colorful and tragic operational life as a test aircraft is an example of what makes the history of flight test at Edwards such a powerful subject matter. I was thinking, wouldn’t it be great if that if that airframe still exists, if it could find its way to the new Flight Test Historical Foundation Museum at Edwards ? So much more to this story and aircraft that I wish I could go on, but for now all I can say is the skies of the Antelope Valley once paraded some really interesting aircraft for us gravity-bound earth walkers to see in flight and they really did shake our souls!

Until next time, Bob out…