Born in Duluth, Minn., on Valentine’s Day, Feb. 14, 1913, Anthony ‘Tony’ LeVeir began life with the last name of Puck.

When his father passed away, Tony’s mother moved her two children to California for warmer weather. She remarried when Tony and his sister were teenagers and her new husband, Oscar LeVeir, gave the children his name.

During several interviews, Tony LeVeir recounts the epic 1927 flight of Charles Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic Ocean to Paris, France, as his inspiration to learn to fly. Upon hearing the news of Lindbergh’s flight he proclaimed to his mother, “I’m going to become an airplane pilot!” His ever-supportive mother said, “That’s wonderful Tony, just remember to be a good one.” Obviously those words from his mother stayed with him throughout his life.

While at an event in Hawthorne, Calif., he recalled how as a teenager, he was going down the aisle of the Balboa Theater on July 4 and spotted what he thought was a dollar bill. He and his friend were barefoot, so he picked it up with his toes. “I unraveled it and it was a $10 bill,” Tony said. “The first thing that came into my mind was to take a flying lesson the next day.”

He went to Santa Ana Airport to get his flying lesson, but they said he was too young and he didn’t have a student permit, which cost $10. He left that airport and went to Whittier and received his first 20-minute flying lesson for $5. “That started my flying career,” said Tony.

“I was totally devoted, 100 percent devoted to aviation,” he said during the interview. “I could think of nothing else and I think that is what carried me through all these years.” He gave credit to his supportive mother and father. He said, “That kept me going, too, and I just fell into one good thing after another.

“I have to give credit to so many people who helped me,” Tony said. “I was an airport brat, a grease monkey. I was the ‘go-fer’ at the airport. I did everything, I learned to work on engines and airplanes; I was an accomplished mechanic at about 16 years old.”

He was so absorbed with the thoughts of flying that he dropped out of school and hung out at the local airport, doing whatever he could to earn a little money to pay for flying lessons. He was completely driven to learn to fly.

His first job was with the Whittier Airways Company as a night watchman and mechanic, making $100 a month. “$80 for flying lessons and $20 to live on,” said LeVeir. “I never dreamed of being a test pilot,” he said. “I wanted to be an air mail pilot and an airline pilot, but I couldn’t pass the physical examination.” As it turned out, for some reason it was an erroneous exam result. Years later, the required test for checking heart function was changed to an EKG. He tried again and he passed.

Over a two year period before he soloed, he had six different instructors. After earning his pilot’s license, he received his Commercial License in 1932, when he was 19 years old.

In 1936, he started air racing, first in Los Angeles and then in Cleveland, Ohio. He also flew in the Thompson Air Race in Cleveland, winning the Greve Trophy.

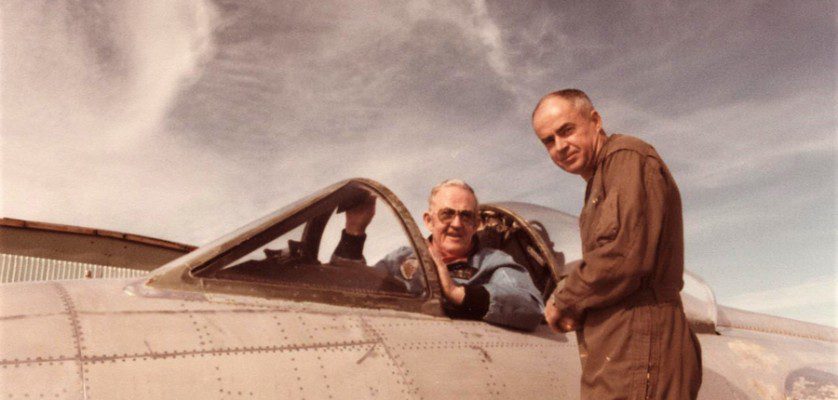

LeVeir told great stories of his flight experiences lacing them with many expletives. In the 1960s and 1970s, he was a regular at Mojave Airport, visiting with General Manager Dan Sabovich and other pilots up and down the flightline.

Al Letcher had the first Hawker Hunter to be flown into the United States and LeVeir had to sit in it and share flying stories with his friend.

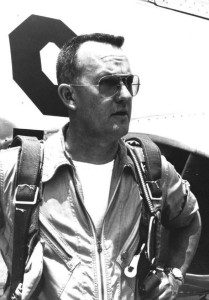

LeVeir joined Lockheed Aircraft Company in 1941 and ferried Hudson bombers from California to Canada for the Royal Air Force. He later trained and checked out pilots in the Hudson and its transport variant, the Lodestar. His job description was changed to engineering test pilot in 1942, to fly the PV-1 Ventura. His test flying was instrumental in proving the Lockheed P-38 Lightning design. He and chief engineering test pilot Milo Burcham alternated flying dive tests, to observe the design’s performance at transonic speeds. To demonstrate the reliability of the design in the hands of a skilled pilot, he performed aerobatic shows for students at the Polaris Flight Academy at War Eagle Field in Lancaster, Calif., at the corner of present-day Avenue I and 60th Street West.

He was instrumental in solving the compressibility issue, or ‘mach tuck,’ that plagued the P-38 during high speed diving maneuvers. Kelly Johnson’s team of engineers designed a dive flap to be used while diving at high speeds, so the tail of the aircraft would maintain its authority.

According to online sources, Tony LeVier was responsible for several inventions and contributions to airplane ergonomics and safety. For example, in 1944 he conceived the idea to turn the pilot’s stick grip counter-clockwise in the XP-80 to enable the pilot (who manipulated the stick with his right hand) to have better use and control of the aircraft. The same year, he conceived the idea to place aircraft trim switches on top of the control stick grip; a design feature now universally used on all military and some civil aircraft around the world. In 1949 he conceived the first practical afterburner ignition system for jet fighters. He also contributed to the design refinement of the Lockheed hydraulic-boosted and full-power flight control system, used in all aircraft since the P-38 of World War II.

Other inventions included his 1951 design of the automatic wing stores (ordnance) release for military aircraft to prevent aircraft crashes from asymmetric loading due to malfunctions; now universally used by all military combat aircraft; and his 1952 invention of the Master Caution Warning Light System for aircraft, the universally used system on most aircraft in the world.

The following information was published after LeVier’s passing: “In 1954, the XF-104 Starfighter roared aloft on its maiden flight. Called “The Missile With a Man In It,” LeVier used it to become the first man to exceed 1000 miles per hour. The F-104 became the standard bearer of the Free World, and 15 countries adopted it as their superiority fighter. For the next ten years, LeVier managed Lockheed’s Starfighter Utilization Reliability Effort with NATO countries, contributing immeasurably to saving lives. He also assisted famed aviatrix Jackie Cochran when she set a new world’s speed record for women.

“LeVier flight tested Lockheed’s top secret U-2 in 1955, which later earned banner headlines when one was downed while making reconnaissance flights over the Soviet Union. LeVier’s active test pilot career ended when he became Lockheed-California’s Director of Flight Operations. Of him, Lockheed’s famed “Kelly” Johnson stated: “I like LeVier to fly my aircraft first because he always brings back the answers.” Years later, LeVier piloted a Lockheed “Tristar” from California to Washington, D.C., on the first completely automatic flight of a commercial plane.”

LeVier retired from Lockheed in 1974. During his career he distinguished himself as the world’s foremost experimental test pilot. He made the first test flight of 20 different aircraft and flew more than 240 different types, more than any pilot in history.

His first flights included many well-known aircraft, including: Lockheed XP-80; Lockheed T-33; F-94APrototype; F-94C Prototype; XF-104 and the U-2, to name a few.

Tony LeVier died after a lengthy illness battling cancer and kidney failure at his home in California on Feb. 6, 1998.