LANCASTER, Calif. — An honor guard of Young Marines marched into American Legion Post 311, in crisp camouflage uniforms and shined boots, hoisting the red, white and blue flag of the United States, and the red stripes on yellow field flag of the vanished Republic of South Vietnam.

A room full of mostly old men from the armies of both nations stood to salute the flags, and to honor the youths who carried the colors. Each member of the flag detail in the youth group was born decades after the Vietnam War that ended 47 years earlier.

A ceremonial table honoring POW-MIAs, with rose and white tablecloth was laid out lovingly at the foot of the lectern where Post 311 Commander Doug Cook stood and saluted.

On the morning of April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces converged on Saigon, the collapsing capital city of South Vietnam in a juggernaut of tanks and artillery. As the city was falling to the communists, a 4-year-old boy named Quy Nguyen was hiding under his bed. His parents were turned back from their attempt to escape the besieged city.

Across town, another young child of Saigon, Brittanie Ngo, was in a crush of terrified refugees holding tight the hand of her father, Bang Ngo. They ran for their lives to crowd onto an overloaded C-130 Hercules transport, one of the last flights out.

“It was sweltering in the C-130,” an aircraft designed to carry as many as 100 troops, but with three times that number of terror-stricken passengers packed in. “There was no air-conditioning, and then, at 30,000 feet it was freezing.”

But the flight eventually carried the Ngo family and other refugees, first to Wake Island, then to Camp Pendleton, Calif.

It was the “day we lost everything,” her father recalled. “It was the day that evil won, and everything was gone, freedom, democracy, human rights, everything.”

Quy Nguyen, who hid under his child’s bed amid the shelling and air attacks, would wait more than five years to escape the communist regime of Vietnam. He and his family and dozens of others nearly drowned in the South China Sea. At 9-years-old, he survived because the pregnant wife of a Hong Kong fishing boat implored her husband to rescue the Vietnamese “boat people.”

“More than 100,000 perished at sea,” remarked Bang Ngo, the former South Vietnamese army officer, who took his daughter by hand onto the C-130 flight from the airport under attack.

The elder Ngo added, “But today is not to cry. It to show our respect, our appreciation and gratitude to more than 2 million young men from America who fought valiantly and idealistically to protect freedom and democracy against the communists.”

Father and daughter Ngo and Colonel Nguyen were joined by sister refugee Kim Dunlap at the American Legion Post on the 47th anniversary of the fall of the Saigon government to communist force. Their purpose at was to thank Vietnam War veterans who fought in their country in one of America’s longest wars. More than 58,000 Americans were killed in the 20-year war in which 2 million Americans served.

Brittanie Ngo, a program manager at Edwards Air Force Base, attired in a white formal Vietnamese gown — Ao Dai — hugged and embraced veterans. She spoke to a room filled with white and silver-haired men, men young more than 50 years ago in the war of their youth.

“Please forgive how emotional I am,” Ms. Ngo said. “Every single one of you are embraced in my thoughts and my very being. I can truly say to the veterans who fill this room today that I always feel the debt for the sacrifices of Americans.”

She wasn’t the only emotional presence in the room. The memories shared by father and daughter Ngo, by recently retired Air Force Col. Nguyen, by Kim Dunlap, brought the audience of more than 150 veterans and their guests to their feet.

Gerry Rice, a Vietnam combat infantry scout dog handler with the 101st Airborne Division, welled with tears. Rice recalls he spent his 22 months in the Army, with most of that time in Vietnam, walking “point” patrol with his canine counterpart. It was frightening, sometimes deadly work, and he came home wondering was it was for. The April 30, 2022, gathering at the Legion post offered an answer.

“I never have hugged a Vietnamese refugee before,” Rice said. “She so filled my heart. I told her that for many years I felt like a loser, and she made me feel what we did, and what we fought for, was not in vain.”

Ms. Dunlap, a licensed clinical social worker at Edwards Air Force Base, responded, “It was because of men like you who fought so hard, and made the ultimate sacrifice.”

Dunlap arrived at the age of nine in Atlanta, Ga., under the Humanitarian and Orderly Departure programs. Such hardships and the losses of 100,000 people at sea prompted the United Nations to act, and the United States to embrace the programs.

“My father was a senior lieutenant in the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). He was a prisoner for six years, tortured and forced to be re-educated. Because of his sacrifice, we were allowed to apply under the Humanitarian Operation.”

For Dunlap it meant arrival in a strange new land, without language, or friends. But it also meant “water, lights,” and “to be able to play outside without fear of stepping on a land mine.”

Community sponsors and the refugees themselves supported the event, with dinner served at no cost to the veterans. The dinner, however, was more than a meal. It offered an opportunity to reflect on service, on sacrifice, on the loss of loved ones and friends, and the meaning of living in a country that embraces individual initiative and freedom.

Each of the speakers, who began life as children and refugees, rose to achievement, and honors, with strong ties to the nation’s armed services.

Colonel Nguyen recounted how his family eventually settled in Colorado Springs, Colo., near the Air Force Academy.

“My dad told stories about the war, and his friend who was serving in the same area as the U.S. 1st Marine Division,” Nguyen recounted.

During that combat operation, his father said his friend gazed on a village in the valley below and told him, “After this mission I will marry a girl down there.” With tears in his eyes, Nguyen’s father shared that his friend was killed.

“He did not make it back alive,” Nguyen said. “He did not get to marry the girl he loved.”

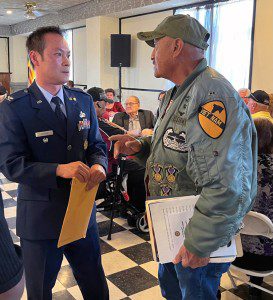

Nguyen, wearing his blue officer’s uniform with its many rows of ribbons, spoke haltingly.

“My father made the brave decision to risk all our lives rather than be subjected to living under the communists,” he said.

So, the Nguyen family followed the journey of 1.2 million other Vietnamese who left their homeland in the face of daunting danger.

“Freedom is like oxygen, when you have it you don’t think about it much, but when you miss it, you will do whatever it takes to regain it.,” he said. “In May of 1995, I graduated from the University of Colorado and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force, and that is the rest of the story of how I became Colonel Nguyen today.”

The ravages of war, as he experienced it in Vietnam and later as an American officer, involve “unimaginable cruelty and suffering,” he said. But, he added, the experience affords the opportunity for “bravery and acts of kindness.” Amid war, remembering kindness is key to sustaining humanity.

For the daughter of Bang Ngo, the United States as her adopted homeland is an interchangeable term she learned from her father, as he undertook to master English in the American idiom. The terms father Ngo used with equal facility, she said, were “Jackpot!” and “Potluck!” She offered her father’s linguistic journey as a jumping off point for gentle humor.

Addressing her fellow Americans, Brittanie Ngo said, “Because of your sacrifices, I hit the ‘Potluck!’”