Army Staff Sgt. Gerald L. Endl spent more than two years serving in the South Pacific before he lost his life, but he did so with honor while saving several of his platoon-mates.

For making the ultimate sacrifice so that others could live, Endl earned the Medal of Honor.

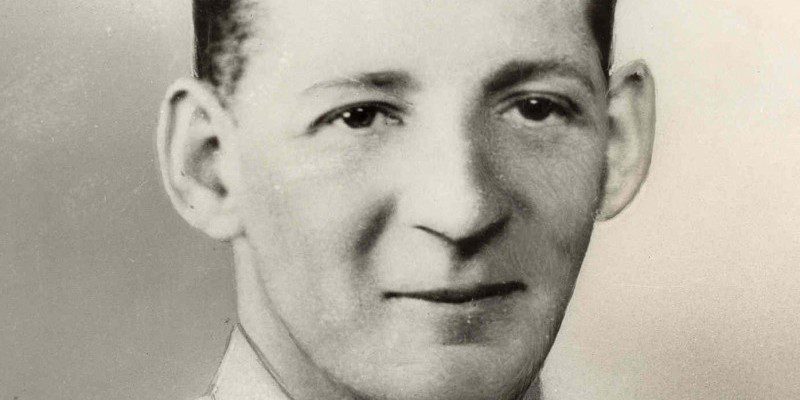

Endl was born Aug. 20, 1915, in Fort Atkinson, Wisc. His parents were Ferdinand and Ellen Endl, and he had two older sisters, Isabel and Mildred.

According to the 1930 census, Endl worked for a messenger for Western Union while he attended Fort Atkinson High School. After graduating in 1933, he served in the Wisconsin National Guard for a short time while working at the James Manufacturing Company as a machinist for poultry equipment.

On Jan. 1, 1941, Endl married his wife, Anna Marie, then moved about half an hour south to Janesville, Wisc. About three months later, he was drafted into the Army. Endl trained in Louisiana and was eventually placed with the 128th Infantry Regiment, 32nd Infantry Division.

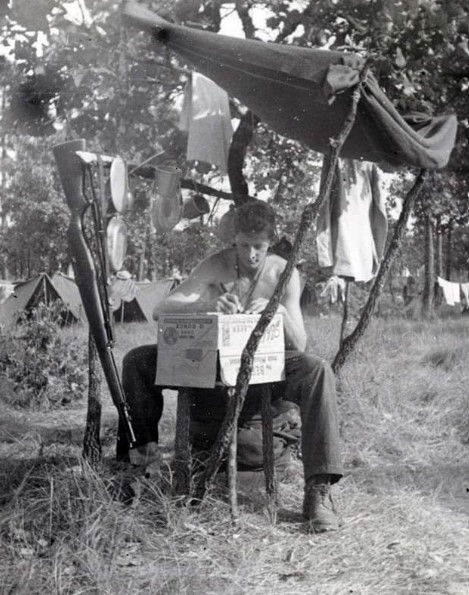

The 32nd was slated to deploy to England, but as the war shifted to the South Pacific, so did their plans. The division was instead rerouted to Australia and New Guinea in April 1942.

In December 1942, Endl was wounded in the shoulder and knee during battle. He was hospitalized in Australia for several months before returning to active duty in May 1943. Previously, he received the Purple Heart for his actions and was promoted to the rank of sergeant. A few months later, he was promoted to staff sergeant.

Endl managed to survive more than two years of fighting overseas; unfortunately, he never made it home.

On July 11, 1944, the 28-year-old’s platoon was taking part in Operation Cartwheel, which aimed to neutralize a major Japanese base at Rabaul. According to a War Department release, Endl and his platoon had been on the move and hadn’t eaten or rested in more than 30 hours.

Endl was at the front of the company’s lead platoon on a jungle trail near Anamo, New Guinea, when they ran into enemy troops. The Japanese quickly unleashed rifle, machine gun and grenade fire. Endl’s platoon leader was injured, so Endl quickly took over command. He had his platoon get into a firing line at a fork in the trail toward which the enemy attack was directed.

The dense jungle terrain made it hard for them to see and move easily, so Endl tried to make his way further down the trail to a grass clearing. But as he did so, he detected the enemy — which had at least six light and two heavy machine guns — trying to close in on both flanks.

A second platoon was sent to move up on Endl’s platoon’s left flank to help, but the enemy closed in on them quickly, threatening to isolate and annihilate both units. Twelve members of Endl’s unit had been wounded, while seven others had been cut off by the enemy’s advance.

Endl knew that if his unit was forced back further, those stranded men would likely be captured or killed by the Japanese. So, he decided to try to rescue them, even though he knew it was likely a death sentence. Endl pushed on alone through heavy fire, engaging Japanese soldiers in a close-range firefight for a good 10 minutes. His effort held off the enemy long enough for his platoon-mates to crawl forward undercover, grab the trapped and wounded men and get them to relative safety.

However, four wounded men were still left on the trail in enemy territory, and Endl refused to leave them there. One by one, he brought them back to safety. It was while he was carrying the last man in his arms that he was struck by a heavy burst of fire and killed.

Thanks to Endl’s efforts, all but one man was evacuated, and both platoons successfully got away with their wounded in tow.

Endl’s comrades later remembered his bravery.

“He knew that to attempt to move ahead into the face of the enemy advance was almost certain death,” said Army Staff Sgt. Edward R. Lane, Endl’s platoon-mate who was later killed in action. “Yet, in his cool and determined manner, he said, ‘I’ve got to get those men out.’ And he went out alone to get them.”

Another platoon-mate, Pfc. Andrew W. Danielinko, called Endl “the most calm and efficient man I ever saw.”

On March 27, 1945, Endl’s widow was given the Medal of Honor on his behalf. It was presented to her in their hometown by Army Col. W. Lutz Krigbaum, the commanding officer of Camp (now Fort) McCoy, about two hours northwest of Janesville.

Endl was initially buried in New Guinea, but his remains were repatriated in July 1948 and interred in St. Joseph’s Cemetery in his hometown. His medal was eventually donated to the Wisconsin Veterans Museum.

Streets on numerous military bases have been named in Endl’s honor.

Editor’s note: Medal of Honor Monday highlights Medal of Honor recipients who have earned the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.