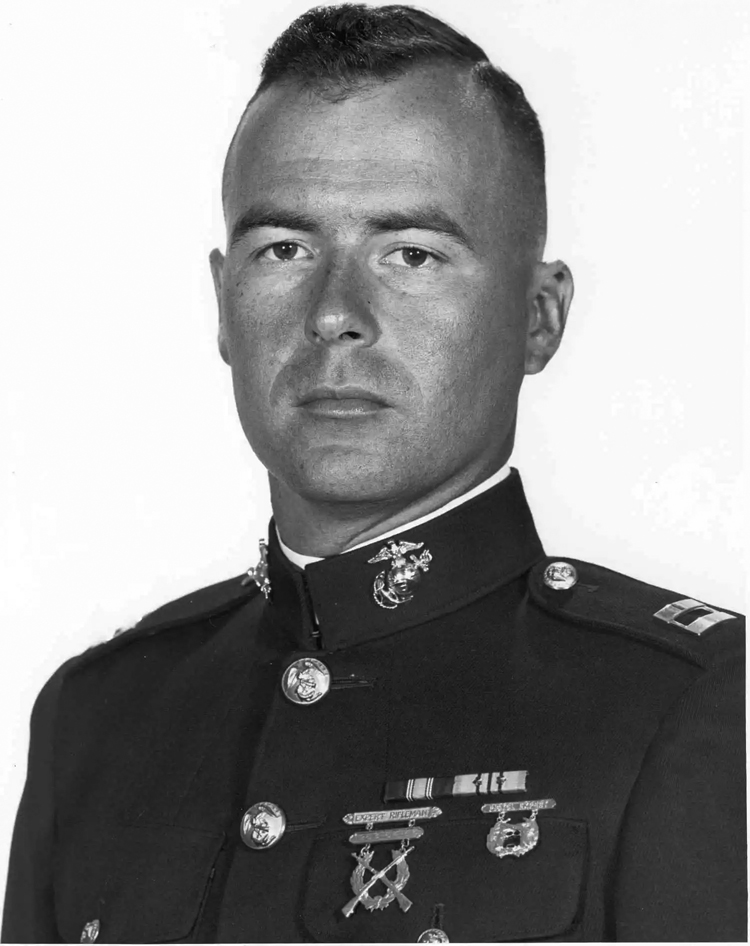

Marine Corps Col. Harvey Curtiss Barnum Jr. barely had time to adjust to Vietnam as a young lieutenant before he found himself commanding a company in the middle of an enemy ambush.

Barnum’s calm demeanor and swift decisions helped stabilize his badly damaged unit, and they earned him the Medal of Honor.

Barnum was born July 21, 1940, in Cheshire, Conn., to parents Harvey and Ann Barnum. During an interview later in life, Barnum said he and his younger brother, Henry, were fortunate that their parents were both very involved in their upbringing, which is likely where his understanding and love of discipline began.

Barnum was a Boy Scout and played football and baseball at Cheshire High School. He was president of both his freshman and senior classes.

While Barnum’s father was a Marine during World War II, he said he chose the service because of a Marine Corps recruiter who visited his school on a career day. Barnum said the recruiter had listened to the students’ reactions to the other military recruiters and was appalled by their conduct. The recruiter told the crowd that none of them was worthy of the Marine Corps. Like many other students that day, Barnum immediately wanted to prove the man wrong.

“[That recruiter] epitomized what I thought the military was all about — he stood up and took charge and made a big impression on this young 18-year-old,” Barnum said in a Library of Congress Veterans History Project interview.

After graduating high school in 1958, Barnum went to St. Anselm College in New Hampshire, where he joined the Marine Corps Platoon Leaders Class, a summer program similar to ROTC. Four years later, he graduated with a degree in economics and was commissioned into the Marine Corps Reserve.

After training, Barnum was sent to serve with the 3rd Marine Division in Okinawa, Japan, before being stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in early 1965. Later that year, his unit was ordered to go to Vietnam on a temporary deployment, and the first shipment of Marines was slated to leave prior to the holidays. Barnum said that because he was single and most of his fellow Marines weren’t, he volunteered to go.

Barnum arrived in Vietnam in early December 1965 to serve with Company H, 2nd Battalion of the 9th Marines Regiment, 3rd Marine Division. Within two weeks, his unit would be enmeshed in a battle that earned him the nation’s highest award for valor.

The battle

In his Veterans History Project interview, Barnum said his unit was out on patrol when it was called back and flown to a mountain near the village of Ky Phu. They were told they would be replacing another company that had suffered several injuries during Operation Harvest Moon.

On Dec. 18, then-1st Lt. Barnum was the artillery forward observer for the company, which brought up the battalion’s rear as it moved off the mountain to head back toward the village. Suddenly, they were pinned down by enemy fire from a large North Vietnamese force. The ambush separated his company from the rest of the battalion.

“It was the first time I’d been shot at,” Barnum said. “So, I hit the deck.”

Injuries mounted quickly for the company, but Barnum was OK. He quickly surveyed the scene and realized that the company’s radio operator and its commander, Capt. Paul Gormley, had fallen.

“When I … looked around, I could see all these young Marines’ eyes looking at me, and they’re saying, ‘OK, lieutenant, what the hell are we going to do?'” Barnum remembered. “At that point, I started doing what lieutenants do, and that’s giving direction.”

Barnum got up and immediately started calling in artillery, but he said he eventually called off the fire because some of the shrapnel was hitting his men. Without regard for his own safety, Barnum then ran into the open field to grab Gormley and bring him back to relative safety. He said they talked right before Gormley died in his arms.

“The company commander just died, and the radio was still out there [on the field],” Barnum said. “So, I ran out, took the radio off the dead operator, carried it back and strapped it to myself. I got on the phone, called the battalion commander, and told him what happened and that I was assuming command.”

Barnum calmly reorganized and rallied the units around him before leading a counterattack on an enemy trench to their right. He said fixed-wing aircraft in the area couldn’t come to their rescue due to bad weather, but leadership eventually provided them with two gunships to help. Barnum moved through intense enemy fire to get to a knoll where he could call in the air attacks, repeatedly exposing himself so he could physically point out the targets.

When Barnum eventually talked to the battalion commander in the village, the commander said help wouldn’t be able to get them —that Barnum’s company would have to fight its way out or be stuck by themselves overnight.

“I knew that was a nonstarter,” Barnum said. “Casualties were mounting rapidly. Ammunition was getting low, and the ceiling was closing in on us. I didn’t think our chances were going to be very good if we stayed.”

So, Barnum had some Marines clear a small landing zone as he requested and directed the landing of two transport helicopters for the evacuation of the dead and wounded. The lieutenant said he and the remaining Marines then collected their packs and all the equipment that was no longer working and destroyed them “to make ourselves light.” Their next move was to make it about 500 meters across open rice patties to the village without getting hit by enemy fire.

“Squad by squad, when I said ‘go,’ I said, ‘Run as fast as you can. Don’t even stop. The only time you stop is if someone gets shot and you pick them up,'” Barnum remembered.

He said it took about 45 minutes, but everyone managed to make it to the village, which the rest of the battalion was able to successfully evacuate.

Committed to service

Days later, Barnum learned that he was recommended for the Medal of Honor. He received it on Feb. 27, 1967, from Navy Secretary Paul H. Nitze during a ceremony at Marine Barracks Washington. His family, some friends and several other Marines he fought with were able to attend.

Barnum, who was promoted to captain in 1966, returned to Vietnam in October 1968 to command the same battery he’d served with during his first deployment. He remained in the Marines for a long time, retiring after 27 years of service in August 1989. A few years later, Barnum married a woman named Martha Hill.

During his Veterans History Project interview in the early 2000s, Barnum said that the medal can sometimes be a burden, but he’s never forgotten what it stands for.

“I’ve worn this medal in honor of those great Marines and corpsmen who fought with me on the battlefield that day who didn’t walk off, or walked off seriously wounded,” he said. “There were no superstars, but I happened to be the quarterback calling the plays.”

Throughout his life, Barnum has continued to work with the military in an official capacity, as well as with veterans and service members through various organizations. He served as deputy assistant secretary of the Navy for reserve affairs from 2001-2009. He was also designated the acting assistant secretary of the Navy for manpower and reserve affairs in January 2009.

In 2016, it was announced that a new guided-missile destroyer would be named for him. Five years later, in April 2021, Barnum attended the keel-laying for that ship, the USS Harvey C. Barnum Jr.

Editor’s note: Medal of Honor Monday highlights Medal of Honor recipients who have earned the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.