WASHINGTON D.C.— It is 21 steps that an Honor Guard soldier guarding the Tomb of The Unknowns takes, heels tapping while a hushed crowd watches his solemn line of march.

At 21 steps, in perfect dress blue uniform, the silent soldier executes an “about face,” shouldering an immaculate M-14 ceremonial rifle with chromed bayonet. The soldier repeats the process until relieved by the staff sergeant of the “Old Guard.”

All eyes were on the sergeant who escorted the relief guard out, changed the guard, and returned to his post with the guard who was just replaced. But eyes were also on rows of veterans in blue shirts who were watching the ceremony in silent respect.

So goes the “Change of Guard” ceremony at one of the nation’s most sacred memorials, the Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier, who rests “in honored glory … known but to God.”

Among the troops, an entire “L-shaped” row with about half of them seated in wheeled “transport chairs,” there was a truck dispatcher, a cook, a submariner, plus a collection of “grunt infantry” soldiers, joined by Marines, airmen, sailors.

These were the veterans of Honor Flight Kern County Flight 46, seated, and standing, in the VIP section, because on this warm spring day at Arlington National Cemetery, they were the very important people. D.C. tourists standing across from them on the marble steps had their eyes on them, too.

Among them was one authentic combat hero, and one conscientious objector, both drafted during the Vietnam War, both served with honor and distinction. There were two female veterans of the Vietnam Era, one Army soldier, one Marine. There were fighting sailors of the Navy, and flying crew chiefs of the Air Force and Army helicopter assault squadrons.

In their youth, some of these veterans fought until their shed blood transformed into Purple Heart medals, fighting in places like the Mekong Delta, the Ashau Valley, the Central Highlands.

As the late author Joseph Galloway who served alongside them put it, “In their youth, they were tigers.” As Steven Mayer, reporter for the Bakerfield Californian put it, there were too many different jobs on the Honor Flight manifest to list “but everyone had a story,” and simply too many stories to tell.

Mayer attended the first Honor Flight Kern County, more than 10 years ago, with 20 World War II veterans attending. In the years since, and 45 flights later, the local non-profit has emerged into a regional movement.

In company as close as they ever kept in a barracks or ship, veterans ranging back to the Korean War, through the Cold War years, and the Vietnam War Era, spent an intense three days days together as the honor roll of Honor Flight 46.

They flew via charter from Bakersfield to the nation’s capital for a lightning-round tour of all the armed forces memorials, and the grandeur of the Capitol where they were hosted in the House chamber by their elected representative, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. He was joined by Rep. Mike Garcia, R-Santa Clarita, a decorated Navy pilot who flew during the Iraq War.

No veteran paid a penny out of pocket. The dozens of “Guardians” and volunteers who escorted the veteran cohort paid their own way.

“The Honor Flight is our gift from the people of Kern County, and Bakersfield,” said Janis Mattoon Varner, one of the four group leaders who tended to the diverse flock.

One Army veteran, Anthony Kitson, marked his 90th birthday the day the group departed Bakersfield Airport.

“It was the trip of a lifetime,” said Kitson, who shifted from active Army to spend more than 20 years working for the Department of Defense in Thailand, Laos and Vietnam. In those days he flew aboard Air America, the CIA-owned airline.

“I think the Honor Flight was one of the most significant experiences of my life,” Kitson said.

Kitson was born in London in 1933, and was seven years-old during the Battle of Britain. Along with many other British childen, he was evacuated to the country during the Blitz.

During the round of tour stops, veterans stepped off the bus to visit Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps memorials. The Marine Corps Memorial, seated on a strip of highway near Arlington National Cemetery features the gargantuan statuary of the Iwo Jima flag raisers. Vets of every branch formed up at their memorial and saluted for the camera.

Flight 46 veterans also visited the Vietnam Memorial, the Korean War Memorial, the World War II Memorial. They also visited memorials of the nation’s historic leaders, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dr. Martin Luther King, and our 16th President who preserved the Union, Abraham Lincoln, and the Women’s Memorial at Arlington.

“There’s only one monument in Washington,” Eddie, the bus driver said. “It’s the Washington Monument. The others are memorials.”

As the veterans walked or moved by chair, hundreds of schoolchildren turned out, joined by teachers and parents. As veterans stepped into the memorial entryways they were greeted by applause, and children handing them flowers and notes.

“We want them to experience this,” Varner said. “We want them to understand that they are honored, and their service appreciated and recognized.”

Schoolchildren by the dozens pressed “Thank You” notes into their hands.

My note said, “People don’t really have an idea of what you go through. I want to thank you for being brave,” from Max Vogt, a sixth grader.

The Honor Flight non-profit program has 136 “hubs,” or chapters nationwide. The mission emerged nearly 20 years ago, to honor quickly departing “Greatest Generation” World War II veterans, most of whom are gone. Now it is Korea and Vietnam and elder veterans of the Cold War.

At the World War II Memorial, middle school girls presented me with a red carnation, and beaming smiles.

Honor Flight Kern County is an all-volunteer non-profit created to honor veterans of Kern County and surrounding areas with veterans as far away as the San Fernando and Antelope Valleys. Priority is given to the oldest first, any veteran of World War II — and those from any conflict who are terminally ill.

As we approached the Vietnam Memorial, the sense of hallowed ground pervades the quiet. More school children beckoned us with handshakes, and bowed heads. It was a little overwhelming, especially for those who served in Vietnam.

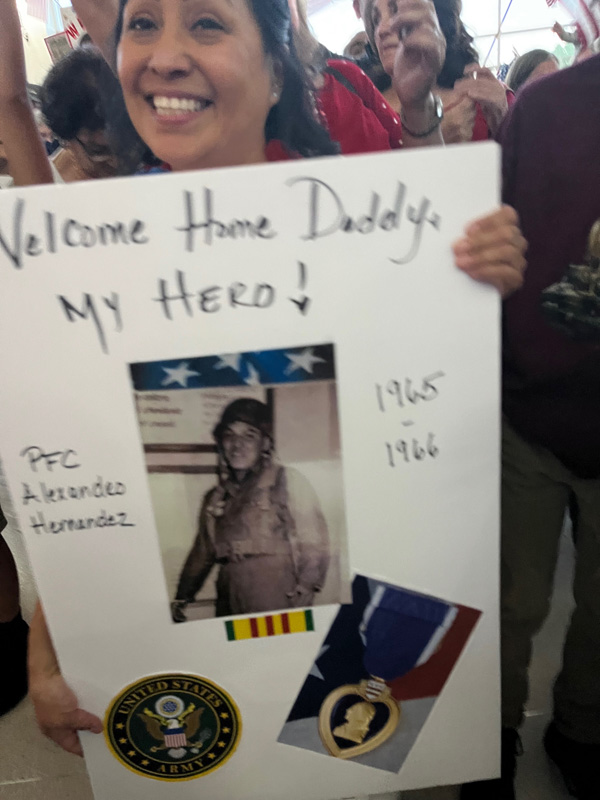

“I was at Ia Drang with 1st Cav,” Army veteran Alex Hernandez said. “Not at the time of the big battle, but not long after.” Wounded, he received the Purple Heart. He added, “I was with 7th Cavalry. Our motto, ‘Garry Owen,’” referencing the Irish song that has been the 7th Cavalry Regimental march since the Battle of Little Big Horn.

Hernandez was recalling the epic fight between two 7th Cav battalions of the 1st Cavalry Division, Airmobile, heavily outnumbered against a regiment of North Vietnamese Army regulars. The battle was recounted in the book “We Were Soldiers Once,” and Young” and the Mel Gibson film, “We Were Soldiers.”

That book was co-authored by the late Joe Galloway and Lt. Gen. Hal Moore. Galloway, a UPI journalist at the Ia Drang battle, hired me into the Washington D.C.

bureau of UPI in 1981. Galloway had a soft spot for hiring veterans.

Two names inscribed on that sloping inverted pyramid of black granite with the 58,000-plus names of all Americans killed in Vietnam held a personal connection. It is said the Vietnam Memorial is the most visited war memorial on the Washington Mall.

I searched out Jimmy Nakayma, a badly wounded soldier assisted by Galloway at Ia Drang where he was horribly burned by a U.S. napalm strike that mistakenly hit U.S. troops. Nakayama died two days later, Nov. 17, 1965, within days of his son’s birth. Nakayama’s name is among 237 listed on Panel 3E of the Vietnam Memorial, so many killed in the space of a few days.

The other name I found was Richard K. Carter, killed Nov. 19, 1967, two years later. Carter, on Panel 30E. Carter was older brother to my Antelope Valley Vietnam Memorial volunteer comrade, Augie Anderson, Air Force veteran. We are not related, but we are connected.

My Army hitch began about a month after “MAC-V,” Military Assistance Command, shut down on March 29, 1973. The Army sent me to Europe as a paratrooper, and my service was with an armor recon unit scouting walls, barbed wire and mine fields along the Cold War border of East Germany, a state that dissolved in 1989 with the Soviet Union’s fall imminent.

Volunteers known as “Guardians,” made us all feel honored, whether we served in Korea, Vietnam, or the Cold War. Whether we worked in a cookhouse in Greenland, or a nuclear code bunker in Germany, we were welcomed.

Guardians monitor medication, push “transport chairs,” and assist veterans any way they can. My companion, Anthony Kitson, friend of more than 30 years, was escorted by Guardian Fabian Millan, a communications expert with the shoulders of a linebacker. Millan and Kitson made fast friends.

“It’s an honor to work with Anthony Kitson,” Millan said. His sentiments reflected the enthusiasm of all the more than 50 Guardians, some among them veterans, some just earnest, kind, and helpful.

“I have always been patriotic, and I go to every veterans event I can,” Guardian Cissy Teagarten said.

Two female Vietnam Era veterans attended, Donnie Alexander, Marine, and Glenda Dukes-Sonkur, Army, both from the Antelope Valley. Together, they explored the many galleries of the Women’s Memorial with the history of service dating back to the American Revolution.

No World War II veterans flew on Flight 46. Of 16 million Americans who served more than 75 years ago during World War II, only about 100,000 are living.

At a ceremonial dinner, each veteran was summoned to hear a short paragraph about their service read aloud by Group Leader Glen Nakashima. Each was presented a flag flown over the Capitol presented by McCarthy’s staff.

During the service, Earle Cooper, a draftee who became an officer, was recognized for his valor fighting with the 101st Airborne Division in a battle the history books call “Hamburger Hill.” Everyone in the room rose to their feet and applauded.

“I appreciate it,” he said, quietly. “Please,” he added. “I am the same as all the others.”

On the flight home, each vet received a mail bag packed with letters of gratitude from family members, from the “Police Wives of Bakersfield,” from volunteers with Honor Flights Kern County, from more school children, and friends.

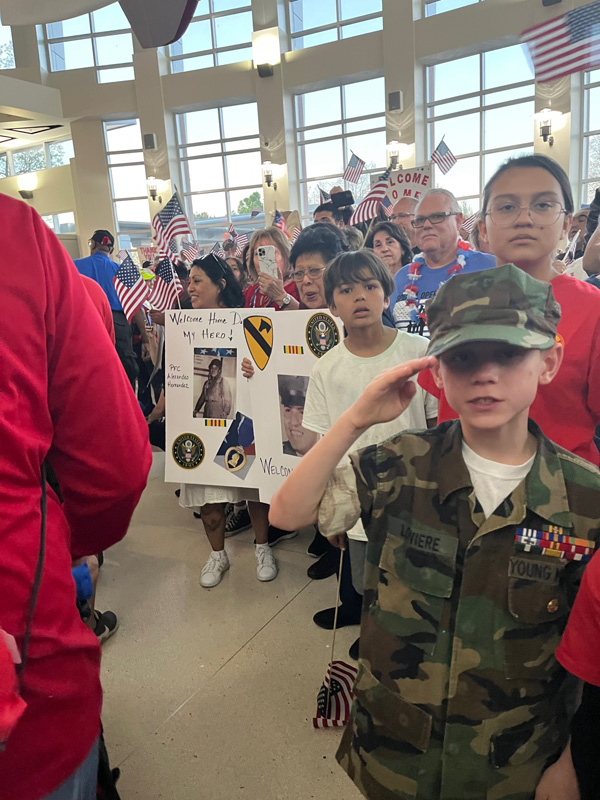

Travel weary but jubilant, the vets trooped off the aircraft on return to Bakersfield. Huddled together and tired, we heard a din and roar. Through the corridor, we sighted flags, Old Glory, dozens of flags waved. We heard applause. The applause rose to a roar of cheers and a band played. High school sports teams, motorcycle clubs, American Legion, VFW and veteran groups, and family members and friends waved, and grabbed at the veterans. Women of the American Legion offered decorative blankets. People clapped, stamped their feet and many cried, whether veteran or members of the welcome home crowd.

It looked like half of Bakersfield turned out. For troops who returned home, quietly, often with little or no welcome more than half a century ago, it looked and sounded like the Fifth Avenue parade they never got. It was the kind of parade that happened at the end of World War II. And that was how it felt.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army veteran, a paratrooper who served in the Cold War and covered the Iraq War as embedded journalist with local National Guard troops. He serves on the Los Angeles County Veterans Advisory Commission.