TOCCOA, Ga. – Most people round the world are familiar with the word “Currahee!” first heard it during an airing of the Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks-produced historic miniseries, “Band of Brothers,” about an iconic company of 101st Airborne paratroopers who jumped on D-Day.

“Currahee! Three miles up! Three miles down!” formed the gasping war cry from the original aspiring paratroopers of World War II, and the actors who portrayed them more than 50 years after history’s greatest war. They chorused together as they ran up a Georgia mountain to toughen up for the ordeal that lay ahead.

Hard to believe it is more than 20 years since “Band of Brothers” first aired in the week following the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and that the series continues to air, having become a kind of “It’s a Wonderful Life” enduring cinematic tribute to the U.S. military. The series, based on the Stephen Ambrose book of the same name, exerts its hold in streaming and gift sets as D-Day 80th anniversary looms.

On a recent summer Sunday, I joined dozens of my veteran comrades – we call each other brothers and sisters – and grunted it out, some of us running the “Three Miles Up” that was the Band of Brothers daily training task. Others of us, many past 50 years, were content to hike. Which is what I did.

We were not aging Baby Boomer hikers and weekend joggers. We still “Stand Alone, Together,” as veteran paratroopers. We jump together too. Even now.

A day earlier, we parachuted, hurling ourselves in “stick formations” from the open door of a C-47 troop carrier aircraft, a flying museum piece that dropped paratroopers on June 6, the Day of Days, in 1944.

We prepared for our jump as the “Band of Brothers” did. The atmosphere in a “ready room” before a jump is less the case of being tense, than of being intense.

In the ready room adjoining the airfield, the check list is everything.

Every belt, strap, hook, buckle, fastener and pin must be connected to the satisfaction of a Jumpmaster, the commander in the aircraft. If it is not right, it can be fatal. The check list, and attention to the detail that goes with it, is life.

“What do you think about this seal?” Staff Sgt. Jordan Whittington, an active Army soldier, asked the senior Jumpmaster, a retired Green Beret officer, about a thread that seals the reserve parachute.

The Green Beret veteran officer’s first name is same as mine, and he decided we were “Team Dennis.” During the final check this is an extraordinary relief, because Lt. Col. Dennis Harrison knows so much more about the gear than I do, and I am reasonably experienced, with 111 jumps in my logbooks.

“The seal is OK,” Jumpmaster Dennis ruled. “It’s a little different than I would do it, but it’s OK.”

With that, the two men sealed the Velcro flap on my reserve parachute. The rest of my gear was almost ready, the MC-1D Army-issue parachute strapped to my back, and legs, chest strap hooked, and Reserve in place, with quick release strap. Jumpmaster Dennis grins at me like he’s smiling at a rookie trooper.

“What is it about you and kit bags, Anderson?” he asked.

The kit bag that rides between the leg straps was loose. I tightened them until the fit was snug. Lt. Col. Dennis nodded, and it was time to board for our jump.

“The aircraft will be flying at 100 mph, with jumpers out at 1,300 feet,” Darren Cinatl, the senior Airborne Operations commander said. “Has anyone got a problem with that?” No one had a problem.

We listened, our ears perked toward the sky for the C-47, which moments before put 15 paratrooper veterans out over the greenbelt and tarmac of Toccoa Airport.

Nicknamed the Skytrain, this D-Day vintage aircraft flown by pilots of the Liberty Foundation, is dubbed “Chalk 30.” It swooped in for a smooth landing, its engines sputtering, propellers feathering. It came to a stop, and we prepared to board.

We boarded much as the “Band of Brothers” did on the night of June 5, 1944, before becoming some of the first of 13,000 American paratroopers to drop into the exploding night skies of France before dawn on D-Day. One difference: we were not carrying rifles, ammunition, explosives and about 100 pounds of extra gear.

On the other hand, many of us in the six commemorative teams that jumped at Toccoa Airport on July 8, 2023, were an average of 40 years older than the troops of Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne.

Many of us passed through the rigors of Army jump school 40 or 50 years ago. A few of the team jumpers are active military, like Staff Sgt. Whittington and Master Sgt. Adam Barfield. They choose to jump with us from love of history and veterans. A few civilians jump, too, most from police and fire agencies.

We had come to this rural airport, adjacent to the small northeast Georgia city of Toccoa on a mission conceived by a veteran paratrooper recently retired from the 82nd Airborne Division, Capt. Cinatl, who breathes, eats, and sleeps the historic Airborne legacy begun in 1940 before America’s entry into World War II.

Operation Currahee was Capt. Cinatl’s project, six years in planning.

The mission of our teams was to rechristen the airfield where a young lieutenant earned his jump wings more than 80 years earlier at the dawn of U.S. military parachute operations.

Richard “Dick” Winters led Easy Company from D-Day all the way to capture of Hitler’s redoubt, the “Eagles Nest” in the Bavarian Alps. By the time 101st Airborne arrived at Berchtesgaden in the first week of May 1945, Hitler was dead by suicide in the ruins of Berlin. World War II in Europe was over.

Winters, played by actor Damien Lewis in the epic “Band of Brothers” miniseries was an exemplary leader, awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions on D-Day. Winters ascended to cultural icon status when his exploits, and those of his paratroopers, became known worldwide after the series aired in 2001.

“Our mission is a sacred one,” Cinatl said. “We are dedicating this as the Richard Winters Drop Zone, and we are honoring the men who trained for World War II at Camp Toccoa.”

With a Jumpmaster pulling us into the aircraft, we settled into bench seats the same way D-Day jumpers did, in reverse order of when we exit the aircraft. Were we, the aging veterans, ready to jump? We have worked to stay ready for decades, some through decades of war in Airborne units.

Our pilot reassured us, “I have been flying DC-3s and C-47s since 1966,” he said.

The C-47 dubbed “Chalk 30” roared off the tarmac and swung over the dense Georgia greenery, much as another aircraft did that carried Dick Winters and other aspiring paratroopers in 1942.

“Dick Winters!” shouted Col. Chris Farrell, Ret., Airborne vet of Afghanistan and some other 21st century wars.

“Dick Winters!” we shouted back. I wonder, could the man hear us across time?

Our jump commands are catechism. “Get ready!” We shout the words back. “Stand up!” We echo that, too. “Hook up!” Then, “Sound off for equipment check!” We make a final check, and tap the buddy in front. “All OK, Jumpmaster!”

The next moment is the World War II troopers called the “Rendezvous With Destiny.”

“Stand in the door!” And, “Go!” In one-second intervals, we leap into the wind.

At 100 mph, and 1,300 feet above the Drop Zone you have all the air conditioning you will ever want. There’s green earth below, trees, and dense forest. And runway. Landing on grass is best. After that, tarmac, hard, but flat. Stay away from the trees.

Our canopies snap open. We look up, and check to ensure they are trim, without holes or tears. We slip away from our friends in the air to avoid collisions and entanglements. It goes pretty fast, and “Crunch!” Boots on ground, chasing the billowing canopy. We are “All OK!” and almost ready to walk in.

Across Normandy on the morning of June 6, thousands of canopies were abandoned as paratroopers scrambled for their weapons and moved off to engage the enemy.

Thousands of those yards of canopy silk became bridal gowns for the liberated in the years after D-Day.

On our easier summer morning than any morning Easy Company experienced we pull our rigs into that kit bag that rides between the leg straps and throw it on our backs.

The reserve chute hooks to the bag to make an improvised backpack. The ruck is not 150 D-Day pounds, but it’s more than 50, and most of us were more than 50 years. So, good.

That evening, our six teams gathered, hosted by city leaders at a World War II Big Band Dance. Beers were hoisted, speeches, a few, and a toast to Cpl. Lloyd Harvey, a World War II Screaming Eagle veteran nearing his century birthday who flew with us.

“To Lloyd Harvey!” the glasses raise. “Currahee!”

A half dozen teams celebrated christening Toccoa Airport’s green grass as the “Richard Winters Drop Zone.” The teams of jumpers led by Liberty Jump Team, included W & R Vets, All Airborne Battalion, Round Canopy Parachute Team, Phantom Airborne Brigade, and Parachute Group Holland. Dutch Marine commandos who jump annually at Normandy and the “Bridge Too Far” battle sites traveled from the Netherlands.

The Dutch Marine veterans visit America to jump in respect for what the American paratroopers and the Allies did to liberate the Netherlands from the Nazi Occupation. Marine Michael Heezen lives in Arnhem, where the British Airborne fought and failed to take the bridge that could have put the Allies across the Rhine. Jens Jansen, also a Dutch Marine, at 62 had served 44 years in the military, mostly in peacekeeping missions.

“On May 5 we celebrate the day the Netherlands was liberated after five years of war,” Jensen said, noting that his father was displaced, and his mother, like so many in Holland was hungry and malnourished from the occupation.

In September 1944, more than 20,000 American, British, Canadian and Polish paratroopers and glider troops swept into Holland in the pyrrhic “Operation Market Garden.” The effort fell short, “a bridge too far,” but the Dutch people never forgot, and still observe ceremonies annually at the Allied drop zones.

Speaking at the hangar dance, Jensen told his friends and the people of Toccoa, “It is very special to be here where it began for those young paratroopers.”

“To those I never knew, but to whom our country owes so much, we will never forget you,” Jensen said. “Fortunately, I got to meet some of you, old people, beautiful people with a history.”

He wondered about the Allied soldiers “who gave cigarettes to my father, and biscuits to my mother. She always has linked the taste of biscuits to the feeling of her liberation.”

So, everyone lifted a glass and rose to applaud Cpl. Lloyd Harvey, one of the last surviving members of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment from which Easy Company, the “Band of Brothers” originated.

With the toasts done, the end of our Georgia pilgrimage was to summit Currahee Mountain, like those kids who volunteered for the paratroopers more than 80 years ago.

Have to say, the three miles up made me gasp, the way I think any Baby Boomer would who wasn’t training for marathons and Iron Man competitions. The 90-degree temperatures of July, and 53 percent humidity complicated the effort.

The word Currahee, according to the lore, is Cherokee for “Stand Alone!”Currahee is more than a hill, and less than Everest, but in its corner of north Georgia, it dominates the landscape, rising above the forests of the piedmont.

Departing from the 506th rebuilt barracks, runners and hikers were age-grouped in their 40s and 50s among the more recently served, ascending the peak with parachutists in their 60s and 70s, one reliably past 80. The three-mile trail to the top of the 1,739-foot peak ascends at a steep incline until you’re on top and can see all the way to Tennessee. You tap the U.S.G.S. service marker, like the troops.

Summiting Currahee was ritualistic, a completion of the commemorative operation in planning since 2017, according to Dave Krasner of W & R Vets.

“Our mission is to honor the heritage of the World War II veterans, the ones who came before us, and to honor what they achieved,” said project organizer Cinatl, who fought in Afghanistan and recently retired from the 82nd Airborne Division.

In the more than 20 years since “Band of Brothers” first broadcast, Easy Company’s oldest veterans have died, along with most of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II. Even the youngest are nearing the century mark, with about 120,000 still with us, according to Department of Veterans Affairs.

Addressing Cpl. Harvey, that rare surviving World War II veteran, Jansen of Parachute Group Holland said, “Let us never forget your sacrifice and bravery. We have to pass this on to the generation that will never know you.”

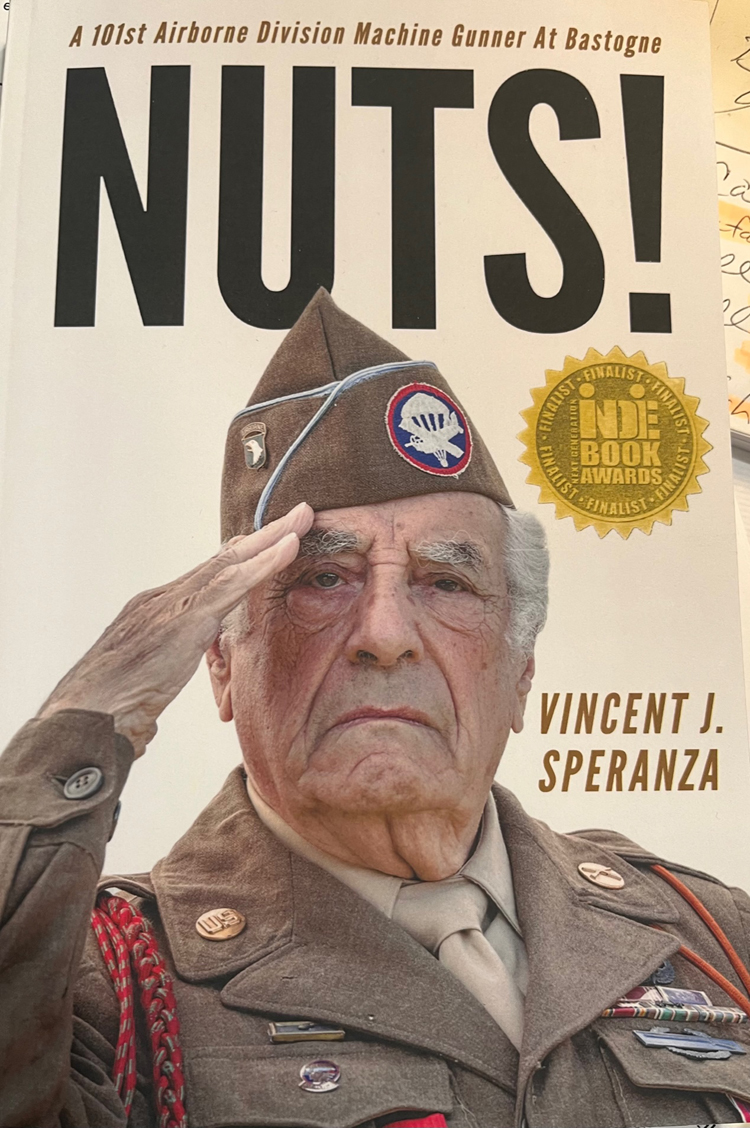

Less than a month after our jump, our Airborne community lost another hero. Vincent Speranza, a 101st Airborne Division hero of the Battle of the Bulge, died Aug. 2, 2023. Speranza’s exploits carrying beer in his helmet to wounded buddies in Bastogne led to the brewing of “Airborne Beer” in Belgium and publication of his autobiography, “Nuts!” a reference to Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe’s retort to a Nazi demand of surrender.

Speranza, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, made his last parachute jump, exiting a C-47 in tandem, on March 27, 2023, his 98th birthday.