LANCASTER, Calif. — The bugler played “Taps” and the lieutenant in his Army dress blues handed the immaculately folded flag to the next of kin.

When they laid 92-year-old Vito Canzoneri to rest at Good Shepherd Cemetery in Lancaster recently, his gravesite was just a short walk from the final resting place of his good buddy, John Humphrey, another paratrooper veteran who lived into his 90s.

Christine Draves, the daughter caring for him at end of life, accepted the flag for the family, a great American family whose patriarch served in extreme combat.

These men were heroes. And as Joseph Galloway, the author of “We Were Soldiers Once, and Young,” would say often during his tenure as America’s foremost war correspondent, “In their youth, they were tigers.”

John Humphrey was one of the early class of paratroopers, jumping into D-Day at Normandy with the 82nd Airborne Division. He was dropped far enough away from the drop zone he had to evade behind German lines for about 10 days. His parents in the States were already notified that he was Missing in Action. Often, that was thought of as a death notice.

But Trooper Humphrey survived, and he made his way back to friendly lines with enough scouted information about enemy movements that he was awarded the Bronze Star. He got his Purple Heart on Christmas Eve, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge.

More than 70 years after World War II, Humphrey and Canzoneri gathered with paratroopers from three succeeding generations for one last hurrah hosted by Mary Buechter in 2016 near Edwards Air Force Base.

John Livingstone Humphrey lived to be 94, and died Nov. 9, 2017, just a couple of days before Veterans Day. Vito Victor Canzoneri was 92, and died a day after Sept. 11, 2023. But if they say it is the dash ó that space in between the date of birth and the date of death that matters, both of these American soldiers made their time on Earth count.

John Humphrey was among the 16,000 Airborne troops on D-Day who delivered the world from the evils of Nazi tyranny. Vito Canzoneri, just a few years younger, was one of those rare birds that made a combat parachute jump into North Korea. In fact, he made two.

Still a child during World War II, Vito Canzoneri finagled his way into the National Guard in his home state of New York when he was too young to shave. When they figured out he was 14, they sent him home and he had to wait a couple of years until he could join the regular Army. He picked the paratroopers.

“If a man will jump, he will fight,” the words of Gen. James “Jumping Jim” Gavin, who jumped into Normandy with the troops on D-Day, and fought alongside his men every day they, fought. Paratrooper generals tended to lead from the front.

By the time that Vito Canzoneri graduated from jump school, Airborne forces had only been dropping paratroopers into battle zones for 10 years. Paratroopers volunteer for parachute duty for many reasons, not least among them the silver wings pinned on their chests after five parachute jumps.

At any time, the Airborne troops make up a small fraction of America’s armed forces. In World War II, at any time there were probably no more than 30,000 in a global war that saw 8 million Americans in uniform. If the Marines rightly call themselves the “Proud and the Few,” it is no less the case for parachute troops.

Vito Canzoneri, not yet 20 years old, joined a proud, hard outfit, the 187th Regimental Combat Team, part of the 11th Airborne Division. The 187th nickname was the “Rakkasans,” a name that the unit appropriated from the Japanese in World War II ó “Men Falling With Parachutes.”

World War II seems so long ago that it is hard to remember that the Korean War came only five years later. It happened when Communist forces of North Korea under the leadership of Kim Jong Un’s grandfather invaded South Korea and almost drove American forces on the Korean Peninsula into the sea, with the line holding at a place called the “Pusan Perimeter.”

Vito Canzoneri of the Antelope Valley fought with the 187th, and along with the Marines who landed at Inchon under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the paratroopers soon joined the fight north of the 38th Parallel. In other words, they carried the fight into North Korea.

How did they get to the fight? The Airborne way, by boarding, then jumping out of perfectly good airplanes.

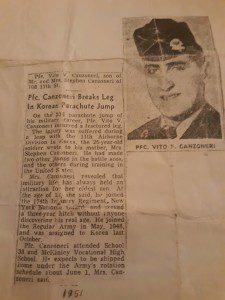

Unit histories report that for Operation Tomahawk, launched on March 23, 1951, about 120 C-119 aircraft called “Flying Boxcars,” ungainly twin-boom tail things, dropped 3,437 paratroopers from the sky. They dropped in 20 miles behind enemy lines, and landed fighting. Vito was one of them, and broke his leg in that jump.

For most people, it is hard to imagine suiting up with about 100 pounds of combat gear, climbing aboard a cavernous clamshell of an aircraft and jumping onto hostile, foreign ground, and being 19-years-old. But General Gavin was correct. If young troopers will jump, they will fight.

In the more than 70 years since that mostly forgotten operation succeeded ó the paratroopers killed a lot of the enemy and took hundreds of prisoners ó it is hard to find soldiers or veterans who have a combat jump. Vito had two. He was what jumpers would describe as “rara avis,” a rare bird.

“He never talked about it,” one of his three sons, Michael Canzoneri said. “I never knew he jumped in above the 38th Parallel.”

Vito came home from his war to marry, and a long marriage yielded six children, all grown with children and grandchildren of their own. Vito Canzoneri worked for many years at Edwards Air Force Base in the supply and logistics areas.

One of his supervisors, Anthony Kitson, held Vito in “highest esteem.” Together the two set off to climb Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the continental United States. Kitson experienced altitude sickness and could not ascend to the top of the 14,505-foot peak.

“Vito tried to encourage me, but I could not go any higher,” Kitson said. “I was really feeling the altitude.”

Vito, leaving Kitson at a safe altitude and location, continued hiking, never having done it before, and made the summit.

At the Rocket Propulsion Laboratory Warehouse, Kitson said that Vito “carried around a newspaper article about the young paratrooper who made the jump into enemy territory during the Korean War.

“He was a true hero,” Kitson said.

At the graveside service, one of the sons, Tony Canzoneri, wore a shirt honoring the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team, the “Rakkasans.”

With “Taps” played and the folded flag handed to family, the soldiers in dress blue departed, leaving paratrooper brothers Humphrey and Canzoneri a close distance from one another in eternity.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army paratrooper veteran who reported the Iraq War with an Antelope Valley unit of the National Guard. He serves as County Supervisor Kathryn Barger’s appointee on the Los Angeles County Veterans Advisory Commission.