LANCASTER – If there is a service that defines itself on its culture and heritage, the United States Marine Corps stands out, and nothing is so celebrated as the Marine Corps birthday.

The Corps was launched Nov. 10, 1775, in a Philadelphia pub, Tun Tavern, and the celebrated lore is that the “Corps of Naval Infantry,” raised, rough men with cutlasses and muskets, formed in a bar amid tankards of strong ale.

So, it was fitting that Palmer Andrews, elder statesman of the Antelope Valley’s Marines, had his life celebrated and his death marked at Bravery Brewing Co., a pub as close in spirit to Tun Tavern as any such gathering spot.

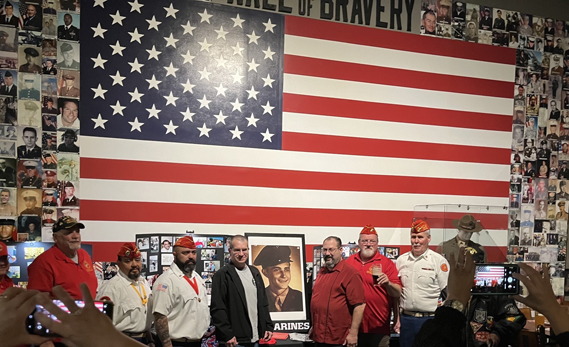

Featuring a flag mural the size of a military helicopter and wall photos of hundreds of veterans, the Bravery microbrewery and pub was co-owned by “Gunny” R. Lee Ermey, the real-life Marine Corps D.I. who starred in Stanley Kubrick’s saga of Vietnam War Marines, “Full Metal Jacket.”

Ermey, who presided at Bravery during several Marine Corps birthday celebrations before his death in 2018, introduced Andrews several times as the Antelope Valley’s senior Marine. It is honored tradition that the oldest Marine, and the youngest, join at the slicing of the Marine birthday cake, cut with a ceremonial saber.

“Grandpa loved cake, and he loved that cake,” his grandson and caregiver Allen Quinton said.

And the Marines gathered revered Andrews as the beloved senior Marine on deck.

Nearly 100 veterans, many Marines, joined by Army, Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard brothers and sisters turned out Saturday, Feb. 17, to lift their glasses in a farewell salute to a beloved comrade.

Family members gathered at a tribute table of photographs, awards and decorations, flags and memorabilia that chronicled Andrews’ adventurous life.

Andrews, who died age 98, on Jan. 11, 2024, was the triple crown of Marine Corps history. Andrews was Marine infantry, the heart of the Corps. He was also a World War II combat veteran who served in combat with the legendary Lewis “Chesty” Puller.

A veteran of the “Blue Diamond Division,” the 1st Marine Division, in the long-lived and fast vanishing population of World War II veterans, Andrew’s life was diamond rare. Of the 16 million Americans who served in WWII, about 119,000 remained alive in 2023.

“My grandpa did not even have a set of ‘dress blues,’” recalled his grandson, Allen Quinton, 55, of Palmdale. “He was in training or combat practically his entire time in the Marine Corps from the end of 1942 to 1945.”

As a Private 1st Class, Andrews served through the most bloody and brutal combat of World War II. His baptism of fire arrived with his arrival on New Britain in the Solomon Islands: sand, rocks, and dense jungle within range of the waiting Japanese enemy.

Andrews, with another 100 or so Marines, was tabbed for a long reconnaissance that became known as the Gilnet Patrol, named for a village. He got his assignment with a curt order from the legendary commander, Puller, who simply pointed and said, “You’re going.”

They lived for weeks in the jungle, hunting and hunted by Japanese, with raw nature, heat and disease as much an adversary as the enemy. Next, came one of the Marines’ bloodiest island fights, ranking with Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The Marines landed on Peleliu Sept. 15, 1944. The National Museum of the Marine Corps called it “the bitterest battle of the war for the Marines.” What had been briefed as a four-day assault of the small island became a battle of more than two months, with more than 2,000 Marines killed and 10,000 wounded.

Japanese dead numbered more than 10,000 with few prisoners taken, according to official histories.

Andrews’ grandson, Quinton recalled, “I was looking for something in one of his drawers and picked up something heavy. I said, ‘Grandpa, what’s this?’” Andrews responded, “’Oh, that, it’s a Purple Heart.’ He said it like it was car keys.”

Andrews would tell friends and veterans, “I was not a hero. But I got to serve with heroes. I got to come home because of the ones who could not come home.”

At the farewell, between the toasts, Tony Tortolano, a Marine veteran and family friend, shared about the elder veteran’s dry humor. Andrews, who considered Tortolano a close friend, called the Baby Boom generation Marine “Sgt. Cold War” because of his service era.

“He’d say, ‘I feel a chill in the room,’” Tortolano recalled. “It must be ‘Sgt. Cold War walked in.’”

In November, Andrews was honored at the Veterans Military Ball, with about six weeks to live.

“We had a beautiful birthday on Thanksgiving. He turned 98 and had cake.” Quinton added, “Seven days before he left us, he said, ‘I’m ready to go.’”

Speaking to members of veteran organizations across the Connecticut-size region of the Antelope Valley, Quinton said, “He wanted everybody to have a part, to raise a glass, and just enjoy themselves.”

The veteran’s son, Larry Andrews, told the gathering that “They are not called ‘The Greatest Generation’ for nothing … they saved the free world.”

Members of Marine Corps League Detachment 930 performed the “folded flag ceremony,” and the organization’s Commandant, Alredo Paniagua, presented the colors to Andrews’ daughter, Jeannie.

The WWII Marine’s son, Larry, told the gathering his father was self-educated. After obtaining his general education certificate after the war, he went on to be a life-long learner who donated a significant collection about the life of author Jack London to Sonoma State University.

Andrews was born Nov. 23, 1925, and grew up in the Chavez Ravine area of Los Angeles, decades before the Dodgers migrated from Brooklyn and razed the neighborhood to erect Dodger Stadium.

By his own account, growing up with a succession of “uncles,” he was offered reform school, or to join the military. He joined the Marines, with his mother signing papers for him at the age of 17, about one year after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Andrews is survived by his son, Larry Andrews, and two daughters, Jeannie Quinton and Christine Johnson. He had nine grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and nine great-great-grandchildren.