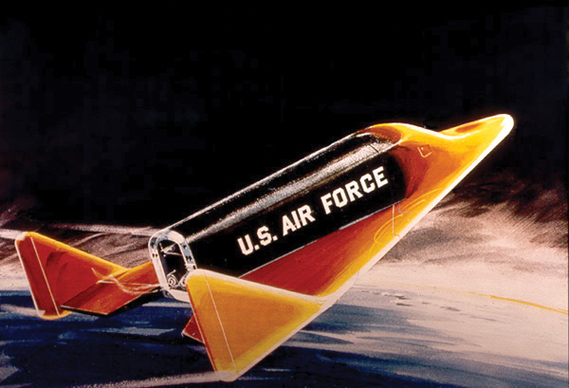

The X-20 Dyna-Soar program is often remembered as one of the biggest lost opportunities in the history of manned space flight.

Evolving from the WS-464L Program, Dyna-Soar had great potential for use as a military space platform as well as civilian science laboratory.

Unlike the earlier Mercury, Gemini and Apollo capsules that were single-use vehicles returning to earth under a parachute system, the X-20 was a winged vehicle, capable of landing on select runways, then refurbished and utilized again.

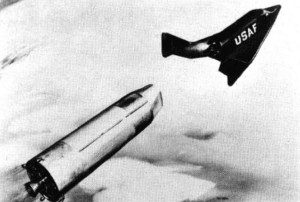

The initial phase of the X-20 flight test program had the vehicle dropped from high altitudes from a B-52C mothership to test atmospheric aerodynamic handing of the vehicle, as well as develop landing techniques at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

The second phase of testing involved sending the X-20 on unmanned and manned orbital spaceflight test missions powered by a Titan III rocket booster which left a large gap in the standard progression of flight testing. The Convair Division of General Dynamics proposed making suborbital test flights using a Little Joe II booster.

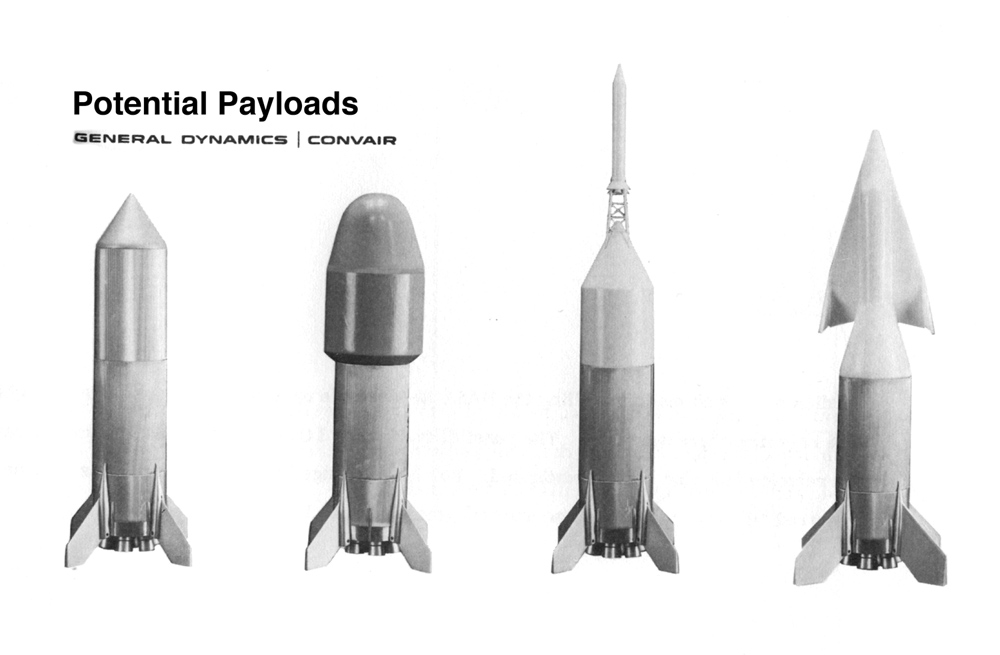

The Little Joe II was a clustered, solid-propellant rocket booster designed as unguided and controllable versions. The vehicle could accommodate one to seven, 40-inch diameter, 100,000-pounds thrust, Aerojet Algol 1D solid rocket motors. With minor modifications the improved launch vehicle (IPLV) could accommodate the more advanced 44-inch diameter Algol IIA motors.

Little Joe II had the reputation as a reliable workhorse of the early manned space program, testing Mercury and Apollo escape and recovery systems from various launch locations. The Little Joe II booster was a versatile rocket with capabilities not found on many systems of the day and could be adapted and configured for several different flight profiles.

Convair proposed making test flights of the Dyna-Soar/Little Joe II combination on an overland range between Edwards and the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Launching from Edwards provided a lakebed in case of an aborted launch and emergency landing. Range instrumentation was already in place at both sites, keeping the range support cost to a minimum.

The Dyna-Soar test vehicle would be mounted atop the Little Joe II booster with a two-part transition fairing, gloved over the X-20 to minimize drag and would be jettisoned prior to separation. This variation of the Little Joe II booster required movable aerodynamic fins, larger than those used on standard Little Joe II launches.

Using a standard Little Joe II booster, the X-20 could be propelled to a maximum speed of 10,000 fps (approximately 6,800 mph) at an altitude near 170,000 feet. With the improved Little Joe II launch vehicle, those figures would rise to a speed of 15,000 fps (approximately 10,200 mph) and an altitude near 200,000 feet. The entire flight covered approximately 582 nautical miles, with the booster impacting the desert floor just over halfway through the flight. The Dyna-Soar test vehicle would experience considerable aerodynamic heating during the reentry phase with the final landing on the alkali flats of the White Sands Missile Range.

The Dyna-Soar suborbital program required a minimum of five test flights: two unmanned flights utilizing the existing automatic guidance, and three manned flights. Convair projected the total price of the five-flight test program at $12.2 million, considerably less than the projected $18 million per flight for a Titan III booster (figures are in Fiscal Year 1965 dollars).

Unfortunately, the Secretary of Defense cancelled Dyna-Soar program on Dec. 10, 1963. That same day the U.S. Air Force announced a new manned space program, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory. Had the U.S. proceeded with Dyna-Soar, it is thought the knowledge gained could have directly impacted the design of the NASA Space Shuttle program.