When I was in Air Force basic training in 2015, my heritage and history courses briefly covered the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) and Grace Peterson, the U. S. Air Force’s first chief master sergeant, but otherwise left me with the impression that women had been excluded from aviation and military roles until more modern times.

My time in the Air Force forced me to reconsider what an aviation role looked like, since when one thinks of aviation, admittedly they think of pilots, but it takes all types of jobs for a successful aviation mission.

From 1942 to 1948, thousands of American women took new roles with the Army, Navy, Marines and Coast Guard. The WASP were the only women allowed to serve as pilots, but they were not alone in serving and supporting aviation missions in a military role.

The idea of American women serving was first proposed in May 1941 when Massachusetts stateswoman Edith Nourse Rogers suggested legislation for the creation of a Women’s Army Auxiliary. That summer, Jacqueline Cochrane and Nancy Harkness Love — both accomplished civilian pilots — submitted their own proposals to the Army to develop a non-combat role for women pilots, according to www.army.mil.com.

There was precedent, as Britain incorporated women into their Armed Forces as early as 1938, including as pilots. But in summer 1941, the United States was not expected to join the war that had justified a need for female soldiers and pilots in Britain, so the American women were considered paranoid, and their proposals dismissed.

However, after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, there was no doubt that women would be needed in some capacity since American manpower was expected to serve on numerous fronts. The military had to deploy manpower to the Pacific, Europe, North Africa, Italy and even the Aleutian Islands.

Each of these theaters demanded men to fill assignments at sea, on the ground, and in the air — all while maintaining a strong presence in the “American Theater” where codes were being broken, battle tactics analyzed, supplies being processed and shipped, radar improved, and troops being trained.

The military needed bodies, and when that need surpassed what the male population alone could manage, they reluctantly called upon the women.

The task of incorporating women into the Armed Forces began in January 1942, when Rogers resubmitted her proposal to create the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, which passed and was signed into law in May 1942.

This allowed women to serve in the U.S. Army, not as equals but as auxiliary members. According to the official history of the WAAC written by Mattie Treadwell in 1954, the first women in the WAAC could only serve with the Service of Supply, later named the Service Forces. The women were originally meant to fill limited roles such as clerical, cooks, bakers and drivers. The majority were assigned to Army air bases, in support of aviation missions despite not being pilots.

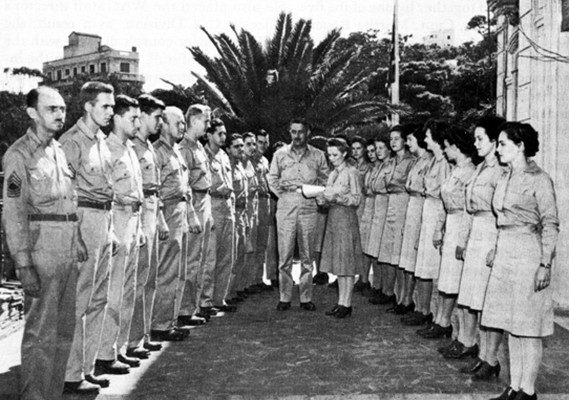

In the first year, more than 60,000 women joined the WAAC. WAACs were not subject to Army regulation or the Articles of War. They also were denied overseas pay and could not receive government life insurance. But by December 1942, the Army was sending the WAAC overseas to places like Algiers, without any of these benefits.

While the WAAC was being established, the Navy was having their own conversations about how to incorporate women into the ranks. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox proposed women serve in the Naval Reserve, but the Bureau of the Budget pushed back, saying the women in the Navy should model the WAAC where the women were serving adjacent to the Army but not as equal members with benefits and military status.

The bill to bring women into the Navy as equal members of the Navy Reserve passed in July 1942. Although officially named the Women’s Naval Reserve, they were best known as the Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Services (WAVES). The WAVES would hold equal pay, rank, and status to the men, but unlike the WAAC, the WAVES were limited to serving in the lower 48 until 1944 when they would be assigned to Hawaii and Alaska.

In September 1942, the first program to create a non-combat role for women pilots was reintroduced. Col. William Tunner asked Nancy Harkness Love to oversee a women’s aviation program with the intent of ferrying aircraft. Harkness Love drafted a plan that went up to Gen. Hap Arnold, who, after some advocacy by Eleanor Roosevelt, directed Harkness Love on Sept. 5 that “immediate action be taken.”

Love started recruiting immediately. This became the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS). They officially launched on Sept. 10, 1942, as a civilian operation. The WAFS were provided with quarters and their own uniforms, but had to pay for them, covering all their own expenses on a paycheck of $250 a month. Due to the rigorous qualifications needed, the WAFS never totaled more than 28 women, and the amount of their assigned work was outpacing their ability to find qualified recruits.

The solution for finding women qualified to fly came from Jacqueline Cochrane. In March 1942 at the direction of Hap Arnold, she had gone to England with a group of American female pilots to serve with the Air Transport Auxiliary. Jacqueline Cochrane returned from England in September of the same year and learned about Love’s WAFS program which had been created in her absence.

Shortly after her return, she received permission from Arnold to create the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) and the first class reported to Houston in October. This provided women with the training they needed for Love’s program. In 1943 the WFTD and the WAFS would merge and become the WASP.

In November 1942, while the WAFS and WFTD were getting women in the air, the same bill that had authorized the WAVES was used to bring women into service in the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard originally called this group Women of the Coast Guard, or WORCOGS. By December of 1942, the first director Capt. Dorothy Stratton, had wisely renamed the WORCOGS to SPARS, short for Semper Paratus, the Coast Guard motto.

Also in November 1942, the Marine Corps announced their intention to accept women into the Marine Corps Reserves, and although the name Femmarines was tossed around, Gen. Thomas Holcombe firmly declared, “They are Marines.” Officially, they are the USMCWR: United States Marine Corps Women Reserve.

While aviation might not come to mind when one thinks of the Marine Corps in World War II, aviation was a key part of the Pacific Theater strategy and heavily involved the Marines.

The main objective of the island-hopping strategy used in the Pacific was to gain control of airfields that allowed the United States to bomb targets closer and closer to the Japanese home islands, putting aviation missions at the heart of the Pacific Theater. This meant that back at home, women serving in the Marines filled in dozens of aviation roles to support the war effort. One of the most common units the WRs were assigned to was known as “AWRS,” Aviation Women’s Reserve Squadron. There were 20 AWRS across the United States and in Hawaii (after 1944) during World War II.

In the official histories written post war, each branch outlined the different jobs the women held, with aviation roles being the most common. In addition to more traditional roles expected of women such as secretarial work or cooking, the WACS, WAVES, SPARS and WRs packed parachutes and managed the supply and loading of aircraft, cartographers, meteorologists, air traffic controllers, mechanics, and so much more. All things that any pilot depends on for a safe and successful mission.

By the end of 1942, more than 100,000 women had entered the military or joined the WASP. In January 1943, Edith Nourse Rogers put forth new legislation to change the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), giving them full benefits and status as members of the Army. The job opportunities for the WAC expanded, to allow women to serve in the Ground Forces, the Service Forces, and the Army Air Force.

By the end of World War II, 40 percent of women soldiers were serving with the Army Air Forces and were known as “Air WACS.” Seven-thousand “Air WACS” served overseas in all theaters of the war, and three of them received the Air Medal for their service. One of the more well-known units in the Army Air Force is the Eighth Air Force, showcased in the HBO series “Masters of the Air.” Although not featured in the show, by September 1944, more than 2,000 WACs were serving with the Eighth Air Force in England.

The Air WACS and the WASPs are the most direct connection to the modern-day Air Force, but the Navy also has its own rich history in aviation. While the Air WACS were expanding their roles into aviation in early 1943, the Navy had incorporated women into aviation from the beginning.

More than 20,000 women in the Navy WAVES held aviation roles during World War II. In 1944, new legislation allowed WAVES and WRs to serve in the Pacific Theater, though they were regulated to Alaska and Hawaii.

Eighty WAVES were stationed in those territories as Air Navigation officers on Naval Air Transport flights. Women in the Navy WAVES served on Cape Cod where there were credible risks of U-boat traffic and German aircraft. The WAVES were responsible for maintaining radar and monitoring radio traffic.

Another important mission taking place on Cape Cod was Long Range Navigation (LORAN) Monitor Station Chatham which was part of the Atlantic chain. This station was unique in that it was run entirely by Coast Guard SPARS, the first to be operated solely by women. The safe navigation of aircraft from the East Coast was dependent on these women in the SPARS and WAVES.

Despite the women’s success in these various roles, it was never meant to be a permanent opportunity. In December 1944, the WASP program was completely shut down to free up jobs for male pilots returning from war.

The women who served in the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, and Marines knew they were facing complete demobilization after the war, as their contracts had been “for the duration of the war, plus six months.”

However, much had changed since 1942 when that plan had been put into place. In 1946, military leadership, aware of the value the women brought to the Armed Forces, instigated plans to make women a permanent part of the military. The Women’s Integrated Service Act was introduced in July 1947 and was signed on June 12, 1948.

The act limited women’s roles, not in the job types, but in how many women could serve with percentages varying from two to 10 percent of the total number of men serving. Women were allowed to serve in many of the same jobs, but once the WASP were disbanded in 1944, it would be another 30 years before women would be allowed to fly for the military again.

Editor’s note: Mel Bloom is a U.S. Air Force veteran and the founder of 3-5-0 Girls, a group dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of women who served their country, through providing resources, subject matter expertise, continuing research, exhibit consultations, and their own pop-up museum. For more information go to https://threefiveohgirls.com and follow them on Instagram @threefiveohgirls

Bibliography:

Letter and survey to to all women holders of licenses, July 29, 1941 in Jacqueline Cochran Papers, WASP Series, Box 2, Survey of Women Pilots July 1941; NAID #120044061. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/research/online-documents/jacqueline-cochran-and-womens-airforce-service-pilots-wasps

Lyne, Mary C, and Kay Arthur. Three Years Behind the Mast . Washington, D.C.: Historical Section Public Information Section, 1946.

“Public Law 689,” Santa Clara University Digital Exhibits, accessed Feb. 6, 2025,

https://dh.scu.edu/exhibits/items/show/2490.

Rickman, Sarah Byrn, and Deborah G. Douglas. Nancy Love and the Wasp Ferry Pilots of World War II. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press, 2014.

Stremlow, Mary V., Free a Marine to Fight: Women Marines in World War II. World War II Commemorative Series. 1994.

The Long Blue Line: 50 Years of women’s service in the Regular Coast Guard! Accessed February 4, 2025.

“The Women’s Reserve (Waves).” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed Feb. 6,

2025.

https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/diversity/women-in-the-navy/waves.html.

Treadwell, Mattie E. Essay. United States Army in WW II Special Studies: The Women’s Army Corps , 16–18. Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, 1954.

U.S. Congress. House. An Act to establish a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp for service with the Army. 77th Congress) (Chapter 312-2d Session) Introduced in the House Jan. 31, 1942. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/artifact/s-495-bill-establish-womens-army-auxiliary-corps-service-army-united-states-january-21

United States Senate Committee on the Armed Forces. Bill. Women’s Armed Service Integration Act (1947).

“WAAF WW2: Women’s Auxiliary Air Force: Women in RAF.” RAF Museum, March 22, 2022.

“Women Airforce Service Pilots.” Women in the Army. Accessed Feb. 4, 2025.

https://www.army.mil/women/history/pilots.html.

Woods, Debbie. “Truman and Women’s Rights.” Truman Library Institute, Feb. 17, 2022.

https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/truman-and-womens-rights/.