We all probably know of Amelia Earhart’s mystery, how Jacqueline Cochran helped form the WASPs and hung out with Chuck Yeager, that astronaut Dr. Sally Ride was the first American woman in space, and maybe that Col. Eileen Collins was the first Space Shuttle commander. We may even know that Maj. Gen. Jeannie Leavitt was the first fighter pilot in combat for the U. S. Air Force.

But there are many women pioneers who are mostly celebrated by aviation historians, people in their hometowns, and air and space museums. Here, randomly chosen, are eight women you may not have heard of before.

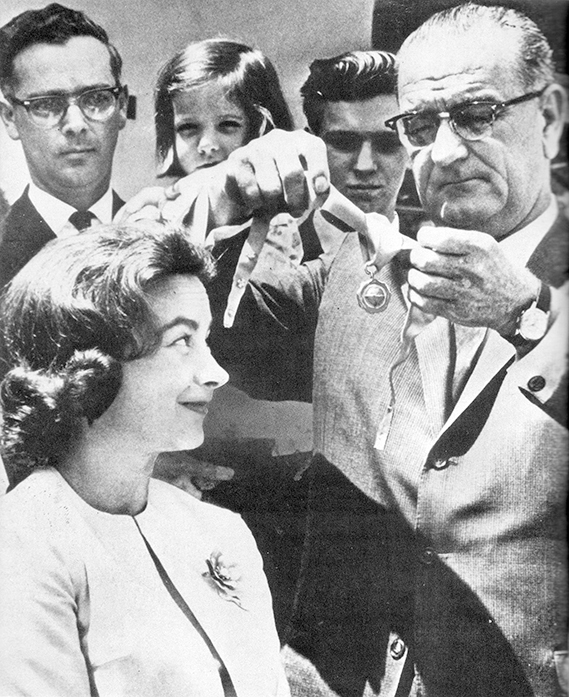

Associated Press photo

Geraldine “Jerrie” Fredritz Mock (Nov. 22, 1925-Sept. 30, 2014) was an American pilot awarded the FAA’s Gold Medal in 1964 by President Lyndon Johnson for being the first woman to fly solo around the world in “Charlie,” a single engine Cessna 180 named the Spirit of Columbus. Begun March 19, 1964, in Columbus, Ohio, and ended April 17, 1964, in Columbus, Ohio, the trip took 29 days, 11 hours, 59 minutes, with 21 stopovers and almost 22,860 miles (36,790 km). The flight was part of a “race” that developed between Mock and Joan Merriam Smith. Smith’s flight path was the same as Ameila Earhart’s final voyage.

Public domain photo

Public domain photo

Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman (Jan. 26, 1892-April 30, 1926) was born into a family of sharecroppers in Texas and attended a segregated one-room school. Interested in flying at an early age, Coleman was stymied by a lack of flight training for African Americans and Native Americans. In Chicago, she saved money and got sponsorships so she could go to flight school in France. On June 15, 1921, Coleman became the first black woman and first Native American to earn an aviation pilot’s license and the first black person and first self-identified Native American to earn an international aviation license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

Navy photograph

Navy photograph

Patricia Denkler (born Oct. 4, 1952) U.S. Navy Lt. Patricia A. Denkler performs a preflight check on a Douglas TA-4J Skyhawk aircraft in 1982. She became the first U.S. Navy woman carrier qualified in a jet aircraft when she landed on USS Lexington (AVT-16) in September 1982. With a father and a brother flying in the U.S. Navy, Denkler had an early interest in aviation. In 1977, she was urged to apply to the Navy Flight program, by then Commander John McCain, which had only been accepting women pilots in 1973. She applied for Aviation Officer Candidate School and was accepted for the October 1977 class. At that time, only 15 women were selected yearly. After Navy retirement, she flew at Delta Airlines for 31 years.

Photo www.cedarhillfoundation.org

Photo www.cedarhillfoundation.org

Mary Goodrich Jenson (Nov. 6, 1907-Jan. 4, 2004) stands next to her Fairchild KR-21 single-engine biplane. In 1927, Jenson became the first Connecticut woman to get her pilot’s license and the first woman to fly solo to Cuba. She was the first aviation editor at the Hartford Courant and first woman to write a bylined column for them. One of the original Ninety-Nines organization of women aviators formed in the 1920s, Jenson was also a director of the short-lived Betsy Ross Air Corps (1929-1933), founded during the Depression to support the Army Air Corps, though it was never formally recognized by the U.S. military.

Library of Congress photo

Library of Congress photo

Harriet Quimby (May 11, 1875—July 1, 1912) was the first woman in the United States to get a pilot’s license in 1911, and in 1912 was the first woman to fly across the English Channel. Her license was Fédération Aéronautique Internationale certificate #37, issued to her by the Aero Club of America. Quimby was also a journalist, film screenwriter for D.W. Griffith, and even tried her hand at acting. She died at the age of 37 in a flying accident. A cenotaph of Quimby was erected at Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in Burbank, CA, which is dedicated to aviation pioneers. Due in part to her influence, the number of licensed female pilots increased to 200 total by 1930 and between 700 to 800 by 1935.

U.S. Army photo

U.S. Army photo

Ola Mildred Rexroat (Aug. 28, 1917-June 28, 2017) was the only Native American woman in the Women Airforce Service Pilots in World War II. Born in Kansas to a Euro-American father and an Oglala mother, she spent much of her youth at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. After a year at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, she decided to fly while working for engineers who were building airfields. She joined the WASPs, trained in Sweetwater, Texas, and was assigned to tow targets for aerial gunnery students, and helped transport cargo and personnel. After the WASPs were disbanded in 1944, she joined the U. S. Air Force as an air traffic controller during the Korean War and worked at the FAA for 33 years.

NASA photo

NASA photo

Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb (March 5, 1931-March 18, 2019) poses next to a Mercury spaceship capsule. Part of the Mercury 13, Cobb and 24 other women, underwent physical tests like the Mercury astronauts believing they might be astronaut trainees. A military child, Cobb’s first flight was in her pilot father’s 1936 Waco biplane, at age 12. She barnstormed at 16 in a Piper J-3 Cub dropping advertising flyers for circuses. Cobb was first woman to fly in the 1959 Paris Air Show, and set the 1959 world record for non-stop long-distance flight, the 1959 world light-plane speed record, and a 1960 world altitude record for lightweight aircraft of 37,010 feet, in her 20s.

Courtesy Pearl Scott Collection, Chickasaw Nation Archives

Courtesy Pearl Scott Collection, Chickasaw Nation Archives

Eula “Pearl” Carter Scott (Dec. 9, 1915-March 28, 2005) at center, a teenaged Scott with her parents and red Curtiss Robin airplane. She was an American stunt pilot and political activist. At 12, pioneer aviator Wiley Post gave her a ride and agreed to teach her to fly. Post also introduced her to humorist Will Rogers. She became the youngest pilot in the United States on Sept. 12, 1929, when she soloed at age 13. In 1972, she became one of the Chickasaw Nation’s first community health representatives and served three terms in the Chickasaw legislature beginning in 1983.