A large crowd of flight test professionals, aerospace aficionados and Northrop Grumman employees past and present, gathered at the AV Fairgrounds Oct. 19 for the annual Gathering of Eagles banquet, presented by the Flight Test Historical Foundation.

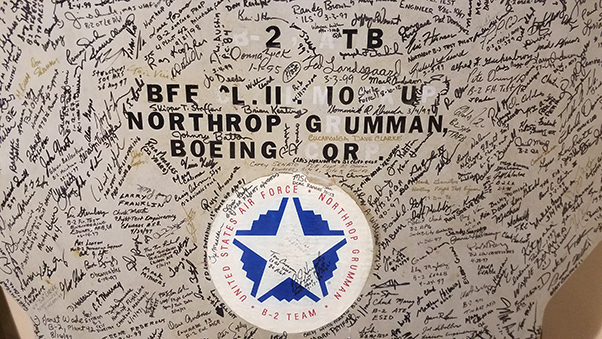

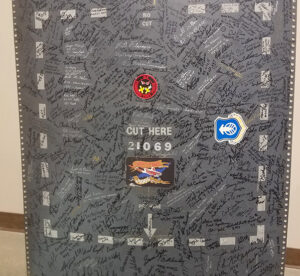

This year’s event, themed “First Flight to First Fight,” celebrated the 30th anniversary of the first flight of Northrop’s B-2 Spirit bomber.

The evening featured a dinner, silent auction and panel discussion with members of the 2019 “class” of Eagle honorees. Moderated by Gen. Arnold Bunch, Jr., commander of Air Force Material Command, the honorees participating on the panel were:

– Bill “Flaps” Flanagan, former flight test Weapon System Operator on the B-2

– Anthony “Tony” Imondi, former B-2 instructor pilot

– Thomas LeBeau, Operational Test and Evaluation Pilot and B-2 test pilot

– Robert Myers, former Northrop Grumman vice president of B-2 flight test

– Otto Waniczek, Northrop Grumman air vehicle manager

Rounding out the panel was former U.S. Air Force Col. Richard “Rick” Couch, former commander of the B-2 Combined Test Force and later vice commander of the 6510th Test Wing.

Also honored posthumously at the event as an Eagle was Col. Frank Birk, former commander of the B-2 Combined Test Force and B-2 pilot.

At the time of Birk’s retirement from the U.S. Air Force, he was the most highly decorated Air Force member on active duty.

As is usual at this highly anticipated annual event, the panel discussion following the induction of the new Eagle honorees was the highlight of the evening. Ranging in tone from highly technical to slyly humorous, the five honorees allowed those in attendance to enter the inner circle of their thoughts, impressions and experiences as they recalled the early years of the aircraft once referred to as the Advanced Technology Bomber. Skillfully moderated by Bunch, and with insightful contributions from Couch and former B-2 Chief Test Pilot Don Weiss, the new Eagles shared memories that were honest and full of valuable information for anyone involved in flight test — including insights that will hopefully be recalled and referred to in the near future, as a new generation of stealth bomber prepares to make history at Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale and at Edwards Air Force Base.

Bunch directed the first discussion question to Flanagan, asking him what his initial thoughts and reactions were when he was first tapped to work on the B-2, which at the time was still a “black” program with little information available for public consumption.

Flanagan recalled his first trip down to Northrop’s facility in Pico Rivera, Calif., with test pilot Cal Jewitt, to see a full-scale mock-up of what was then known as the Advanced Technology Bomber. Having read an article that compared the aircraft’s appearance to that of a living creature, Flanigan said his first impression from a side view of the craft was that it looked like a swallow, or a bird — but upon further inspection, a familiar airframe came to mind. “It’s actually a Northrop flying wing,” he thought, “and it’s going to be really interesting to see if now, the technology is such that we’ve perfected it.”

Tom LeBeau came to his first encounter with the B-2 with a definite pilot’s perspective.

“I flew B-52s before I came to Edwards,” said LeBeau. “In 1984, I got called up to North Base with another group to get briefed on the Advanced Technology Bomber. My impression was ‘at last, the bomber’s up where it can see the targets its going after,’ it was such a big advantage,” compared to his previous experiences of flying B-52 bombing runs “in the weeds,” at lower altitudes.

Otto Waniczek recalled coming off the B-1 program and being recruited to come work on the new bomber.

“The B-1 was a beautiful looking airplane. If you look at it flying, it’s very sleek and more like a fighter.”

Waniczek recalled going to Pico Rivera to look at the mock-up and approaching it first from a side view. “I thought, ‘This thing probably isn’t going to fly very well’… I just couldn’t believe it, I thought, ‘Oh my god, I think I made the wrong decision!’” Time and experience working with the aircraft changed his mind. His 30th anniversary observation? “It’s one of the most beautiful airplanes that I think I’ve ever seen.”

Tony Imondi recalled the culture shock of coming from his former home in Plattsburg, N.Y., to the California desert. “I drove … cross country without my family and when I ran into the headwinds in the Antelope valley, I almost didn’t make it to Edwards.” To appreciative chuckles from the crowd, he continued, “I snuck my family in here in the middle of the night, so they wouldn’t see the tumbleweeds.”

As a relative outsider who had not “come up” through the Test Pilot School at Edwards, Imondi found he had to prove himself worthy and capable to earn a slot on the flight test team. His boss at the time and fellow Eagle honoree, Tom LeBeau, advised him to press on, demonstrate his skill and earn his reputation. “After 4 ½ years of waiting, I finally got a B-2 flight.”

Imondi confessed to not being an early believer in the concept and capabilities of stealth aircraft. “I was a little concerned when they told me I was going to take this 300,000 pound airplane, fly high altitude and nobody would see me, and I could drop bombs all over the place.” But less than six years after the first B-2, the Spirit of Missouri, was delivered, the lessons learned in flight test earned the aircraft its first combat success. “Everything that we found out during flight test turned out to be true during our first engagement in wartime.”

He continued, “25 years since first delivery, we’ve been in five wars — not a single scratch on America’s B-2.”

Commenting on the challenges experienced during the B-2’s development process, former Northrop exec Robert Myers said, “A lot of good people did tremendous things, and had a little bit of bad luck,” a reference to the Congressional decision to cut the B-2 fleet from 132 planes down to 21. Myers recalled his joy when he was invited to be responsible for the B-2 flight test program. “Walking on the tarmac down at Palmdale, and looking over the vehicle and seeing all the resources that Northrop Grumman and the Air Force had, it was hard to imagine that we couldn’t be totally successful.” A period of evaluation followed, flight testing commenced, and program goals were met. “It’s an absolute pleasure to be here and associate with all the folks that helped out way back then.”

Don Weiss asked the panelists to share their reactions and concerns when Congress reduced the number of aircraft ordered from the original 132 down to 21. “One of the bad things was that all the investment had been made — the design work was done, we were testing it and trying to prove it out … all the money had been invested in the program,” said former B-2 CTF commander Rick Couch. “The other thing to think about is that the B-2 has two people in it. The B-1 has four people in it, so you have to train four people in four separate jobs in the airplane; the B-52, six people. If they had built 132 B-2s, there are only two people who have to be trained and you would have one support system for one type of airplane, versus three support systems and three training systems for three different airplanes.” Couch commented ruefully on the lack of wisdom and foresight in reducing the final number of aircraft ordered. Tom LeBeau agreed, recalling that his confidence in Congress was shaken after seeing the cancellation of the B-1A in 1977. He was truly concerned that the B-2 program would suffer a similar fate.

Bunch then broached the topic of what some of the biggest concerns were during the test process and leading up to first flight.

The B-2’s fly-by-wire, low-observable platform was unprecedented, and there were many unique issues that had not been experienced in previous flight test programs.

Northrop Grumman air vehicle manager Otto Waniczek recalled the long days of testing in Palmdale as being exhausting and often disappointing, during the trial and error process of bringing new systems and processes online. There was tremendous relief when things actually began to work and come together. “The team was really dedicated, and they never gave up.” Taxi testing was a major milestone, which brought a new set of challenges. The first aircraft to undergo taxi testing “didn’t have very good brakes. As we were rolling around on the runway at Palmdale, what was only supposed to take a third of the runway to do, took a lot longer.” On one of the test points, the aircraft ended up stopped near the end of the runway, rolled onto the tarmac in the turnaround process, and the landing gear sank into the tarmac. “It was all over,” Waniczek wryly recalled. “Here we have a black program B-2, outside, stuck in the mud, so to speak, and we didn’t know how to get it out — so that was the end of that test day.” A mighty group effort succeeded in digging the gear out and getting the plane towed back undercover, and Waniczek’s next briefing for his crew included a nod to the newly-discovered off-road capabilities of the ATB “All-Terrain Bomber.”

The panelists were asked if there were any standout surprises about the aircraft as the testing process unfolded.

Couch and Waniczek both commented on the resiliency and toughness of the aircraft, as the result of its being so well designed and engineered. “That was pretty impressive, for a new platform,” said Waniczek. “It hugged the terrain like you couldn’t believe,” Myers said.

Following on to an audience question about the B-2’s terrain-following capabilities, as well as the expansion of the program’s requirements that the aircraft be both high- and low-altitude capable (which represented a change from the Air Force’s original request that the B-2 be designed for high altitudes only), LeBeau commented that the changes in those requirements actually resulted in a more capable, robust airframe. “Obviously if you have a low-observable airplane, if you’re at low altitude, you’re even more low-observable.” LeBeau continued, “I pulled 4.65 Gs in a B-2, and it’s a 2G airplane — but it’s a 2G airplane at max gross weight at sea level … there’s more strength in that structure when you’re just flying normal sorties than you absolutely could do anything to hurt. When I pulled that 4.65, it was doing TF (terrain following). It was either that, or the ground!” Imondi added that terrain following added unnecessary expense to the program and when precision weapons and GPS were added to the aircraft, the need for low-altitude flights as a tactic was eliminated.

Weiss wrapped up the evening’s questions by asking the panelists what about the aircraft could possibly be improved. Unwilling to end the evening’s responses on anything approaching a negative note, it was agreed that the B-2’s biggest shortcoming was the failure to install a hammock for the pilot to sleep. This gross design error has resulting in more than one pilot making a run to Walmart to purchase a $10 lawn chair to serve as a sleeping berth — arguably a more cost-effective and comfortable accommodation than anything the government might have added or paid for.

Proceeds from the Gathering of Eagles benefit the construction of the new Flight Test Museum at Edwards Air Force Base, and also support operations at Blackbird Airpark in Palmdale. The new, expanded Flight Test Museum and STEM Education Center outside the Edwards’ gates will serve as an important regional and national resource, where all can learn about the history of flight test. If you would like to support the Flight Test Historical Foundation, or visit the museum, more information is available online at http://www.afftcmuseum.org/.