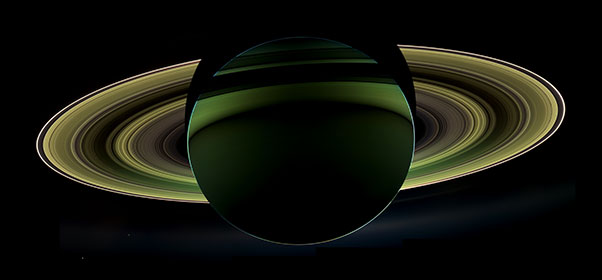

A thrilling epoch in the exploration of our solar system came to a close today, as NASA’s Cassini spacecraft made a fateful plunge into the atmosphere of Saturn, ending its 13-year tour of the ringed planet.

“This is the final chapter of an amazing mission, but it’s also a new beginning,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Cassini’s discovery of ocean worlds at Titan and Enceladus changed everything, shaking our views to the core about surprising places to search for potential life beyond Earth.”

Telemetry received during the plunge indicates that, as expected, Cassini entered Saturn’s atmosphere with its thrusters firing to maintain stability, as it sent back a unique final set of science observations. Loss of contact with the Cassini spacecraft occurred at 7:55 a.m., EDT, with the signal received by NASA’s Deep Space Network antenna complex in Canberra, Australia.

“It’s a bittersweet, but fond, farewell to a mission that leaves behind an incredible wealth of discoveries that have changed our view of Saturn and our solar system, and will continue to shape future missions and research,” said Michael Watkins, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which manages the Cassini mission for the agency. JPL also designed, developed and assembled the spacecraft.

Cassini’s plunge brings to a close a series of 22 weekly “Grand Finale” dives between Saturn and its rings, a feat never before attempted by any spacecraft.

“The Cassini operations team did an absolutely stellar job guiding the spacecraft to its noble end,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL. “From designing the trajectory seven years ago, to navigating through the 22 nail-biting plunges between Saturn and its rings, this is a crack shot group of scientists and engineers that scripted a fitting end to a great mission. What a way to go. Truly a blaze of glory.”

As planned, data from eight of Cassini’s science instruments was beamed back to Earth. Mission scientists will examine the spacecraft’s final observations in the coming weeks for new insights about Saturn, including hints about the planet’s formation and evolution, and processes occurring in its atmosphere.

“Things never will be quite the same for those of us on the Cassini team now that the spacecraft is no longer flying,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL. “But, we take comfort knowing that every time we look up at Saturn in the night sky, part of Cassini will be there, too.”

Cassini launched in 1997 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida and arrived at Saturn in 2004. NASA extended its mission twice – first for two years, and then for seven more. The second mission extension provided dozens of flybys of the planet’s icy moons, using the spacecraft’s remaining rocket propellant along the way. Cassini finished its tour of the Saturn system with its Grand Finale, capped by Friday’s intentional plunge into the planet to ensure Saturn’s moons – particularly Enceladus, with its subsurface ocean and signs of hydrothermal activity – remain pristine for future exploration.

While the Cassini spacecraft is gone, its enormous collection of data about Saturn – the giant planet, its magnetosphere, rings and moons – will continue to yield new discoveries for decades to come.

“Cassini may be gone, but its scientific bounty will keep us occupied for many years,” Spilker said. “We’ve only scratched the surface of what we can learn from the mountain of data it has sent back over its lifetime.”

An online toolkit with information and resources for Cassini’s Grand Finale is available at https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/grandfinale.

Earl Maize, program manager for NASA’s Cassini spacecraft at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Lab, and Julie Webster, spacecraft operations team manager for the Cassini mission at Saturn, embrace in an emotional moment for the entire Cassini team after the spacecraft plunged into Saturn, Sept. 15, 2017.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

After Cassini: Pondering Saturn mission’s legacy

As the Cassini spacecraft nears the end of a long journey rich with scientific and technical accomplishments, it is already having a powerful influence on future exploration.

In revealing that Saturn’s moon Enceladus has many of the ingredients needed for life, the mission has inspired a pivot to the exploration of “ocean worlds” that has been sweeping planetary science over the past decade.

“Cassini has transformed our thinking in so many ways, but especially with regard to surprising places in the solar system where life could potentially gain a foothold,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at Headquarters in Washington. “Congratulations to the entire Cassini team!”

Onward to Europa

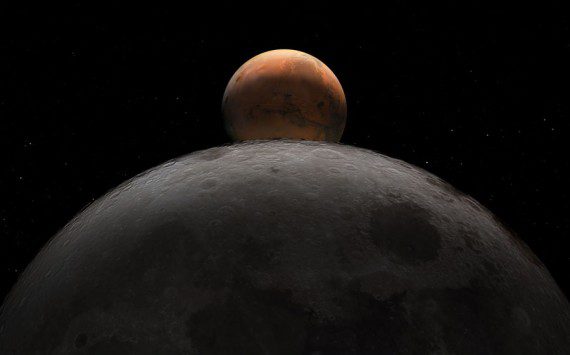

Jupiter’s moon Europa has been a prime target for future exploration since NASA’s Galileo mission, in the late 1990s, found strong evidence for a salty global ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust. But the more recent revelation that a much smaller moon like Enceladus could also have not only liquid water, but also chemical energy that could potentially power biology, was staggering.

Many lessons learned during Cassini’s mission are being applied to planning NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, planned for launch in the 2020s. Europa Clipper will fly by the icy ocean moon dozens of times to investigate its potential habitability, using an orbital tour design derived from the way Cassini has explored Saturn. The Europa Clipper mission will orbit the giant planet — Jupiter in this case — using gravitational assists from its large moons to maneuver the spacecraft into repeated close encounters with Europa. This is similar to the way Cassini’s tour designers used the gravity of Saturn’s moon Titan to continually shape their spacecraft’s course.

In addition, many engineers and scientists from Cassini are serving on Europa Clipper and helping to develop its science investigations. For example, several members of the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer and Cosmic Dust Analyzer teams are developing extremely sensitive, next-generation versions of their instruments for flight on Europa Clipper. What Cassini has learned about flying through the plume of material spraying from Enceladus will help inform planning for Europa Clipper, should plume activity be confirmed on Europa.

Returning to Saturn

Cassini also performed 127 close flybys of Saturn’s haze-enshrouded moon Titan, showing it to be a remarkably complex factory for organic chemicals — a natural laboratory for prebiotic chemistry. The mission investigated the cycling of liquid methane between clouds in its skies and great seas on its surface. By pulling back the veil on Titan, Cassini has ushered in a new era of extraterrestrial oceanography — plumbing the depths of alien seas — and delivered a fascinating example of earthlike processes occurring with chemistry and at temperatures markedly different from our home planet.

In the decades following Cassini, scientists hope to return to the Saturn system to follow up on the mission’s many discoveries. Mission concepts under consideration include spacecraft to drift on the methane seas of Titan and fly through the Enceladus plume to collect and analyze samples for signs of biology.

Giant planet atmospheres

Atmospheric probes to all four of the outer planets have long been a priority for the science community, and the most recent Planetary Science Decadal Survey continues to support interest in sending such a mission to Saturn. By directly sampling Saturn’s upper atmosphere during its last orbits and final plunge, Cassini is laying the groundwork for an eventual Saturn atmosphere probe.

Farther out in the solar system, scientists have long had their eyes set on exploring Uranus and Neptune. So far, each of these worlds has been visited by only one brief spacecraft flyby (Voyager 2, in 1986 and 1989, respectively). Collectively, Uranus and Neptune are referred to as “ice giant” planets, because they contain large amounts of materials (like water, ammonia and methane) that form ices in the cold depths of the outer solar system. This makes them fundamentally different from the gas giant planets, Jupiter and Saturn, which are almost all hydrogen and helium, and the inner, rocky planets like Earth or Mars. It’s not clear exactly how and where the ice giants formed, why their magnetic fields are strangely oriented, and what drives geologic activity on some of their moons. These mysteries make them scientifically important, and this importance is enhanced by the discovery that many planets around other stars appear to be similar to our own ice giants.

A variety of potential mission concepts are discussed in a recently completed study, delivered to NASA in preparation for the next Decadal Survey — including orbiters, flybys and probes that would dive into Uranus’ atmosphere to study its composition. Future missions to the ice giants might explore those worlds using an approach similar to Cassini’s mission.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL designed, developed and assembled the Cassini orbiter.

More information about Cassini can be found at https://www.nasa.gov/cassini or https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov.