A packed house turned out at the Mojave Air and Space Port, Dec. 16 to hear Dick Rutan talk about the 1986 Voyager non-stop, round-the-world and unrefueled trip that took place 31 years ago.

The presentation was part of the monthly Plane Crazy Saturday event that brings aviation enthusiasts to Mojave to see one-of-a-kind and historic aircraft, and hear from some of the leading pioneers in the world of aviation.

“Where were you on this day, at this time, 31 years ago,” asked Voyager Command Pilot Dick Rutan. Many in the audience had witnessed the takeoff of Voyager from Edwards Air Force Base, others were too young to remember.

There were five children in the front row, ranging in ages from 6 to 10, and Rutan involved these young people throughout his talk. He showed one boy with his hands how wide the cabin was and he showed his brother how tall the cabin was, approximately 2-feet by 2-feet. One of the other boys was given the answer as to what material the Voyage aircraft was made from, carbon fiber and the fourth boy was told to remember the other Voyager pilot’s name, Jeana Yeager.

Ninety-nine volunteers worked to build this unique experimental home-built airplane. They participated in the actual carbon fiber layup work and fabrication, communications, manning the command control trailer, office staff, gift shop and so much more.

“Anyone who came to tour the Voyager at Hangar #77, just down the ramp, would have to go through the gift shop and meet Mom Rutan. She didn’t let anyone out without buying something.” Rutan said, smiling.

George Sandy, a pilot from Tehachapi, brought with him a package of dehydrated Shaklee milkshake that he purchased from Irene Rutan in the Voyager Gift Shop. He sold it back to Dick Rutan for $1, and then donated the dollar to Mojave Transportation Museum.

Voyager was financed primarily with individual contributions and a few product equipment sponsors. The project did not receive any government sponsorship.

“The flight was based on winds and weather, which is really backwards to all you guys that fly,” Rutan said. “Normally you plot your course first, but we couldn’t.” The Voyager had a feather light, composite structure with a thin skin and even in very light turbulence the wings would flex and bend. We had meteorologists in the Voyage Command Trailer keeping track of storms and weather for us.

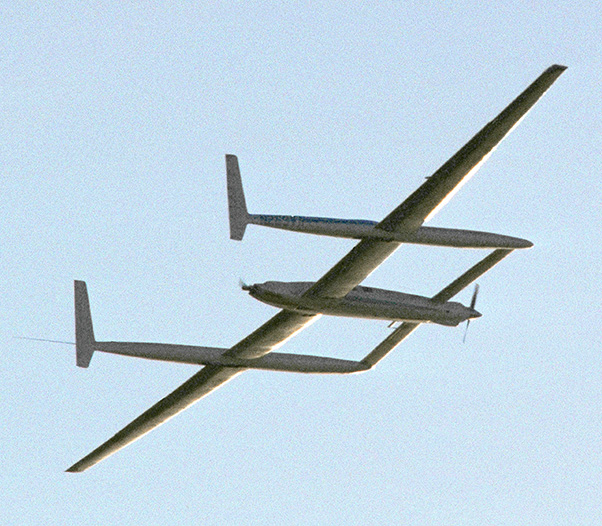

The fragile experimental aircraft weighed 939 pounds and carried more than 7,000 pounds of fuel in its 17 fuel tanks for the historic non-stop flight around the world. Its gross takeoff weight for the world flight was 9,694.5 pounds, of which 7,011 pounds was fuel. When the flight ended nine days, 3-minutes and 44-seconds later, only 140 pounds of fuel remained.

The takeoff, Dec. 14, 1986, was almost catastrophic, as the wings were bending down and the wingtips were dragging on the 15,000-foot runway. The wingtips were severely damaged. Mike and Sally Melvill, and Burt Rutan were flying in a Duchess aircraft nearby and Mike informed Dick that he would have to get rid of the damaged winglets.

Dick applied right rudder to sideslip the aircraft in an effort to make the winglet release. After trying a second time, the winglet fluttered away and the left winglet came off a short time later. There were fears that the winglets tearing off might cause damage to the fuel cells in the wings, but it did not.

Dec. 16 was spent dodging Typhoon Marge and the bands of storms between Wake Island and the Marshal Islands. They made their way through a wall of weather and actually picked up a tailwind.

Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager celebrate their round-the-world flight after landing at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

By day four they were half way around the world over Sri Lanka. When the Voyager crew called Air Traffic Control, they asked the routine questions, what type aircraft, point of origin and destination. Rutan replied type aircraft was Voyager, flight originated KEDW (Edwards) and destination KEDW (Edwards). ATC didn’t believe they were on a world flight and admonished the pilots for such a story. After that experience, Rutan requested that all communication with ATC’s would be handled by the folks in the Voyager Command Trailer in Mojave. “Our phone bill was really high with all of the long distance phone calls,” remarked Rutan.

Later that day, Voyager broke the absolute world distance record of 12,532 statute miles that had previously been set by a B-52 in 1962.

Dick recalled looking down and seeing a long beautiful runway and remembered thinking, oh how nice it would be to land and be able to sleep. But he heard a voice in his head saying, “If you can dream it, you can do it. The only way to fail is to quit!” The voice was that of his mother, Irene Rutan. He said, “I knew we had to keep going.”

During this milestone flight, they navigated around terrible weather and thunder storms, avoided hostile countries threatening to shoot them down, worried about having enough fuel and most of the time ran only one of the two engines to conserve fuel, and suffered with sleep deprivation.

After resolving various mechanical issues, this intrepid team were on the last leg of the flight, flying near the tip of the Baja Peninsula at night, they were transferring fuel when the electrical transfer pump failed. The rear engine coughed and stopped running due to an air bubble in the line. Exhausted, the two pilots had to deal with another life threatening problem. The rear propeller was wind-milling and creating drag, however the wind-milling was the only way to start that engine if they could get the fuel to flow again.

Mike Melvill’s calm voice from Mojave encouraged Rutan to start the front engine, the only engine with a starter. When they were only 3,500 feet over the water the front engine came to life and as they leveled out, fuel had run to the rear engine and it was running too. They leaned the front engine as much as possible, but left it running. There was concern about using more fuel, but fear and tribulation, turned into joy as they were passing near San Diego and airliner pilots started sending them radio messages of congratulations.

Just south of Los Angeles, Burt Rutan and the Melvill’s in the Duchess, met up with Voyager. As they entered into the airspace over the Antelope Valley, Rutan called Edwards tower and was shocked to learn that the Air Force had cancelled all operations just waiting for their return. “I couldn’t believe that they would cancel all flight operations for us little ‘homebuilders’ from Mojave,” Rutan said.

The Voyager aircraft is now on permanent display at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

On Dec. 23, 1986, at 7:32 a.m. Voyager entered the edge of the restricted airspace and saw the dry lake where they would be landing. They flew over the thousands of people who came to witness the landing, making several circuits in the sky with chase planes before landing at 8:05 a.m.

The impressive round the world flight marked the 69th flight of Voyager and led Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager into aviation history forever. The absolute world distance records set during that flight remain unchallenged today. The flight was sanctioned by FAI (Fédération Aéronautique Internationale).

Four days after landing, President Ronald Reagan presented the Voyager crew and its designer with the Presidential Citizenship Medal — awarded only 16 times previously in history.

For their record-breaking flight, the pilots, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager, the designer, Burt Rutan, and the crew chief, Bruce Evans, earned the Collier Trophy in 1986, aviation’s most prestigious award.

The Voyager aircraft is now on permanent display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Whenever he is in Washington, Dick will visit the aircraft in the museum, stand under it and say to himself, “I built that SOB, and I flew it around the world.”