Most any place you can name has a local claim to fame. Salinas has Steinbeck, Nashville has Elvis, Independence, Mo., has Mark Twain and Harry Truman.

For Southern California’s High Desert Aerospace Valley, the big name is Chuck Yeager, prototype for test pilots defined by having what came to be called “The Right Stuff.”

Chuck Yeager, who finally met an inevitable death he cheated in aerial warfare and a high-risk flight-testing career, would have celebrated his 98th birthday this Feb. 13.

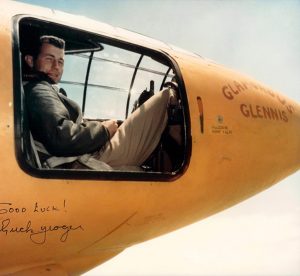

Although he called many places home, from the impoverished Appalachian farm of his childhood to military bases around the world, Edwards Air Force Base (then called Muroc) was the place where he leaped into history by being the first to fly beyond the speed of sound. And from that Oct. 14, 1947, day, it was to Edwards that he returned time and again over the next seven decades.

Worldwide celebrity was unavoidable. Even with his best-selling autobiography co-written with Leo Janus; Tom Wolfe’s novel, “The Right Stuff,” and Hollywood’s movie version of the book, there were different sides to this complicated man experienced by people close to his life and work. Some of those people whose memories fill the gaps are included here. And most of those named or quoted still reside in this High Desert and mountain region of Southern California.

Outliving contemporaries and colleagues can be a downside of old age, but here again, the base of Chuck Yeager’s historical durability is anchored by four Aerospace Valley institutions, the Lancaster-based Society of Experimental Test Pilots, the City of Lancaster’s Aerospace Walk of Honor, Palmdale’s Blackbird Airpark, and the Air Force Flight Test Museum under construction at the Rosamond gate entrance to Edwards AFB.

Completed by the city over 20 years of annual celebrations, the Aerospace Walk of Honor’s bronze and marble monuments along both sides of Lancaster Boulevard tell the stories of 100 test pilots whose extraordinary determination, skill and vision blazed pathways from Earth to the Moon in the American Century of Aerospace.

Gen. Chuck Yeager was in the Walk of Honor’s first class of five test pilots in 1990, sharing the stage with World War II Gen. Jimmy Doolittle; X-15 speed record holder William J. “Pete” Knight; pioneering Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier; and A. “Scott” Crossfield, first to fly at twice the speed of sound. Yeager was the longest surviving member of that class.

Yet history is still being recorded by those who knew Chuck Yeager behind the scenes, on and off the job, and off the record.

One revealing glimpse into General Yeager’s working relationships with subordinates comes from a Lancaster woman who met him when she was a 19-year-old Air Force avionics and systems specialist at her first duty station on Okinawa, Japan. Ruby Thompson said he used to come through the shop where she worked with his F-15s. “He was friendly all the time. He would take time to talk to you,” she said. Seeing Yeager sometime later at Edwards, she again found him to be personable. And he remembered her.

Asked about the topics of conversation, she said it was mostly about aircraft maintenance. Did she know Chuck Yeager enlisted in the military as an aircraft mechanic at age 18 with just a high school diploma and no flight experience? And did she know he lacked a college degree? She hadn’t known all of that, but could understand why he seemed to be so at ease relating to people with shared career interests and mutual respect, something he didn’t always perceive in relations with some of his colleagues and superior officers. He wrote in his autobiography that he felt patronized by “officers who looked down their noses at my ways and accent,” characterizing him as being dumb and downhome.

Dennis Shoffner, retired now in Rosamond after a public affairs career spanning 30 years at Edwards, is one who interacted with Chuck Yeager frequently and long after the general retired but continued to work for $1 a year in support of Air Force public relations.

“He was an excellent guy one-on-one. He just didn’t do crowds,” Shoffner said. Characterizing Yeager as “a solitary guy,” Shoffner recalled Yeager having said on more than one occasion, ‘everybody’s got a handful of give-me’s and a mouthful of much obliged.’ And there were no shortages of handouts, including autographed photos, VIP luncheons, tours, briefings and banquets, which Yeager took in stride as just as much a part of his sworn duty as flying combat missions and flying aircraft to the ragged edge of destruction.

Despite his rank and reputation for being a tough customer, Yeager had a wicked sense of humor Shoffner experienced personally. Recalling an early encounter with Yeager, Shoffner said he was standing at the end of a slow line at a retirement luncheon in the Officer’s Club, when he sensed someone was behind him and turned around. “Chuck’s right behind me,” Shoffner said. “After a beat, all I could think to say was, ‘You buying lunch?’ Chuck looks up and says, ‘Not the way you eat.’”

On another occasion, Yeager casually asked Shoffner, “What’s the song a guy sings in the shower when he’s getting too much sex?” Shoffner didn’t know. “Didn’t think you would,” Yeager said. Everybody got a laugh.

Shoffner said you rarely knew when the playful joker would emerge from the general’s serious business demeanor, even when schmoozing with VIPs. On one occasion, Shoffner and Yeager were leading Orange County Congressman Bob Dornan on an inspection tour of the YF-23 testing program.

Shoffner remembers Yeager pointing out the smallest fixtures and features on an aircraft some distance away, crediting his vaunted 20/10 vision. Later, Shoffner asked Yeager if he could really see what he was talking about? Of course not.

Col. Gary Aldrich, retired U.S. Air Force, had one of the longer-running working experiences with Yeager at the Test Pilot School where Yeager had served as commandant earlier in his career.

“We hung our helmets in the same place, but I was a captain and he was a general,” Aldrich said. But on a personal level, Yeager’s granddaughter was the young Aldrich family’s babysitter.

Yeager trained at the Test Pilot School in 1946 and returned as the schools’ commandant from 1962 to 1966. He returned to the school frequently, making it a practice to address the pilots at graduation, typically delivering the same five or six stories and warning against doing anything in an airplane that could result in having their name painted on a street sign at Edwards. (An inside joke for many years was that all the street signs at Edwards were named in memory of deceased pilots.) Eventually Yeager became the last man standing, so the base broke the curse by changing Mojave Boulevard to Yeager Boulevard, and erecting a Yeager statue on the corner.

The words complicated, complex and challenging tend to come up in conversations with people who knew Chuck Yeager. But even former critics and rivals acknowledge him as a leader possessing courage, vision and personal charm, without actually having attended charm school. As a woman appearing in a video for his Jan. 15 memorial service put it, Chuck Yeager was “someone who didn’t suck-up to generals.”

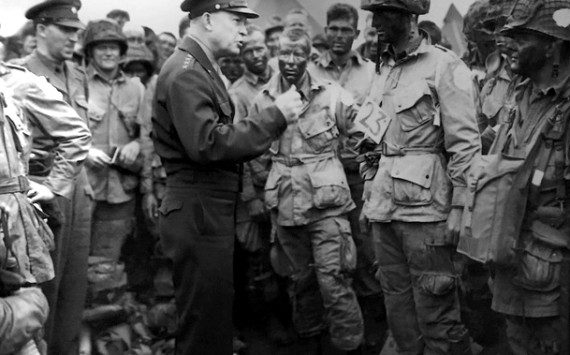

Yeager’s earliest encounter with the minefields planted along the path of public celebrity occurred when he arrived in England with the 363rd Fighter Squadron in Leiston, Suffolk. He described the place as, “three concrete runways surrounded by a sea of mud,” and said the local Brits, “resented having 7,000 Yanks descend on them, their pubs and their women, and were rude and nasty.”

One long-running controversy dogging Yeager’s image revolved around his resume and qualifications for being permitted to do all the things he did faster, cheaper, and arguably better than anybody on hand.

Yeager took the Bell X-1 job after civilian company test pilot Slick Goodlin held out for a payday of not less than $150,000 to make a run at the sound barrier. Yeager did the job for his regular monthly Air Force pay — $283.

Early on there were complaints Yeager lacked the educational pedigree to be an officer, let alone a one-star general and test pilot. That beef ignored the fact that Yeager successfully completed training at the Flight Performance School (later redesignated the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School), in 1946 and finished postgraduate level instruction in the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Ala., in 1951. His graduating thesis was on the development of short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft. Conferral of the title officer and gentleman came with the occupational hazards in learning to fix broken airplanes, overcoming chronic airsickness, being a moving target in an aerial shooting gallery, and flying airplanes built on theories and slide-rule math.

Another thing sticking in Yeager’s craw arose from some of his dealings with the old National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) which grew up to be the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

In media interviews over the years, Yeager complained that after his six years of running the astronaut school at Edwards, ending in 1965, 26 graduates he trained became NASA astronauts. He criticized President Lyndon Johnson’s administration for closing out the Air Force role in space programs and transferring everything to NASA, “and it was a bureaucratic mess ever since.”

Yeager was more ambivalent in comments about whether he was shut out of possible selection as an astronaut because the Mercury space program required a college diploma. He was reported to have balked at applying because the action was coming from Cape Kennedy, and he was put off by the lack of involvement in technical planning and flight control by test pilot astronauts. The first astronauts complained about having nothing to do in space capsules previously occupied by monkeys. Yeager was quoted as saying “I didn’t want to wipe the monkey crap on the seat before I sat down.”

By the time the second astronaut group was being selected, Yeager was over 40, and the question became moot.

A turning point in the relationship between Yeager and NASA began around 1991 when General Yeager unexpectedly dropped by to visit NASA Dryden’s newly installed administrator, Kenneth Szalai. Recognizing that Yeager was esteemed as “the nation’s chief test pilot,” Szalai quickly cleared his calendar for what would be the first in a series of productive meetings pivotal to improving the work of both the Air Force and NASA.

Yeager told Szalai his purpose for the visit was to offer NASA and the Air Force some advice. Szalai remembers that with the economy of words and clarity of messaging for which he was known, Yeager said his first two pieces of advice to both organizations were: “Cooperate and collaborate.” Expounding on that remark, Yeager added, “You guys are on the same field. You have a powerhouse here. Use it!”

Scroll forward a few years, and Yeager’s advice blossomed into a loosely formed alliance in which Air Force and NASA leadership put rivalry in the rearview mirror and searched for opportunities to leverage and maximize their resources through cooperation and collaboration.

Remembering successful outcomes from the old general’s strategic wisdom, Szalai cites:

– Maj. Gen. Richard L. Engle and NASA creating a joint facilities and infrastructure working group to collaboratively explore ways to share resources.” Turned out NASA and the Air Force had separate contracts with the same services vendor, and the Air Force was paying more than twice as much as NASA. (Negotiated money-saving single contract.)

– Working moms at NASA’s private non-profit child care center asked if NASA and Edwards AFB could combine resources to offer child care to military families as well. NASA wasn’t allowed to pay workers, but owned the building, while the Air Force didn’t have a building but could pay staff. (Win/Win)

– Both NASA and Edwards AFB hit the jackpot for their missions and budgets when the alliance approach reached the level of sharing base infrastructure when there were gains to be achieved. That came to apply to flight test radars and structures, communication wiring, aircraft interoperability and some pilot certification rules.

Szalai pointed out that NASA and the Air Force enjoyed successful partnerships in flight tests for the X-15 and the wingless lifting body forerunners to the space shuttle program.

He said, “The X-1 program is the reason the NASA Flight Research Center stands today, as a handful of NACA aeronautical experts from Langley, Va., headed by Walt Williams, joined the military and Bell staff in the assault on the ‘sound barrier.’ AFRC exists because of this first frontal attack to overcome compressibility effects on controllability and performance of aircraft at high speed.”

Recalling Yeager’s many visits to the center, Szalai said Yeager flew with NASA’s Rogers Smith in an F/A-18 and gave high compliments to Walt Williams and the NACA engineers. Szalia said Yeager was “a national leader for the advancement of high speed, high performance military fighter aircraft. Before the human spaceflight program, he was the most recognizable pilot in the United States.”

Possibly because of his long life and career in the national spotlight, some of the Yeager lore and legend is filled with seeming anomalies and contradictions. In one case, Yeager was criticized for speaking harshly to a woman test pilot in the presence of her peers. In contrast to that incident Yeager actively supported Jacqueline Cochran, the first woman to break the sound barrier. He was a mentor in the 1950s and 1960s, flying the F-86 chase plane for her flights prior to the supersonic dash, and flew as her wingman in the record-setting flight.

When Cochran, who died in 1980, was selected to be posthumously inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor Class of 2006, Yeager volunteered to accept the award on behalf of the Walk of Honor’s first woman test pilot honoree.

Then, too, Chuck Yeager remained nimbly open to suggestion and to learning lessons from near-misses and hard landings. In a 40-page MACH BUSTERS section published by the Antelope Valley Press for the 50th Anniversary of Yeager’s first supersonic flight, Aerospace reporter Jay Levine interviewed Yeager on the test pilot’s thoughts after a half century.

In that interview, Yeager’s reflections showed a mind open to fundamental changes in strategic positioning influenced not just by new technology, but by shifts in economics, social trends and global priorities.

The pilotless airplane is the future of military aerospace — reducing risks to humans and more precisely engaging targets.

The quest for greater speed is no longer a key goal for military fighters. “If a guy is running, you can launch a missile that travels about two Mach faster than your launch speed and catch him.”

“Stealth is the key to survivability.”

“People bitch and whine about reductions in force. But in today’s fighting, you don’t need as many airplanes.”

The Air Force should stop the practice of rotating air crew members to new assignments every two years. Because the new aircraft and systems are more complex, the crews should be held together longer to keep the most practiced and experienced people at the controls.

Known by those close to him as a strong and competent leader and “someone who doesn’t suck-up to generals,” the father of two daughters and two sons had a soft spot for kids.

Local resident Michael Cleare, who was a child when he fell in love with flying, was nine-years-old when he came to know American hero Chuck Yeager. The unlikely friendship began when Cleare’s grandpa rewarded the boy’s good grades with a surprise gift of an hour-long flying lesson every summer Saturday morning.

The adventure began with a 5 a.m. alarm and a drive to Barnes Aviation at Gen. William J. Fox County Airfield, west of Lancaster. Owner Bill Barnes, son of legendary woman aviator Florence “Pancho” Barnes, would be Michael’s flight instructor. Among the adults sitting around having coffee and conversation that morning was an older guy who looked familiar to Cleare. The man wore a crumpled old hat that young Michael had seen before. It was the hat Chuck Yeager wore in a cameo appearance in the movie, “The Right Stuff.”

From that morning’s introduction, the retired general and the boy he always called “young man” formed a bond. Michael became a kind of summer Saturday morning mascot, being lifted into cockpits of warbirds and listening to hangar flying yarns.

On one Saturday morning, responding to a question from Yeager, Michael said he planned to spend the afternoon swimming at Jane Reynolds Park Pool in Lancaster. At the pool later that afternoon, Michael recalls kids hearing propeller warbirds circling in the sky above. Michael identified the planes as World War II P-51 Mustangs and gull-winged F4-U Corsair fighters, flown by his friends. “They didn’t believe it,” he chuckles. But he knew it was his private air show.

The dual instruction flying lessons ended with the passing of Bill Barnes and Michael’s sixth-grade year. Not allowed to fly solo until his mid-teens, Michael took a break through high school and eventually earned his private pilot license. He says the last time he saw Chuck Yeager was at the old AV Fairgrounds on East Avenue I, where Yeager was selling autographed copies of his book. Michael lent a hand.

Yeager’s generous contributions to science programs won him a lot of friends and admirers. Yeager set up and underwrote an educational foundation. He partnered both publicly and privately with national organizations supporting youth outreach and education not just in science and aerospace, but for wildlife conservation and habitat preservation. He was characterized as the most visible advocate for Conservation since President Teddy Roosevelt.

Maj. Gail Harper of Edwards AFB Civil Air Patrol Combined Squadron 84 recalled that the official Air Force auxiliary organization created the Chuck Yeager Decoration to recognize achievement of its senior members.

Yeager was instrumental in building support for the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Young Eagles program that introduced hundreds of thousands of American children to the personal thrill and wonder of flight in light aircraft.

Perhaps summing up the life of Gen. Chuck Yeager in one sentence videotaped for his online memorial service, actress Barbara Hershey, who portrayed Yeager’s beloved wife of 45 years, the woman he called Glamourous Glennis, said of the man, “Boy, was that a life well-lived or what?”

Chuck Yeager by the numbers

Flying Hours Logged: 10,000

Aircraft Types Flown: 350

X-Plane Test Flights: X-1, 34; X-3, 3; X-4, 7

Other significant flight tests: Captured Russian MiG-15, F-86, F-100

Awards and Honors

1947 — Awarded Collier and McKay Trophies for breaking the sound barrier

1953 — Harmon Trophy

1976 — Congressional Silver Medal

Life Timeline

Feb. 13, 1923 — Born, Myra, W.Va.

June 1941 — High school graduation

September 1941 — Joined Army; trained as aircraft mechanic

Summer 1942 — Under the Flying Sergeants program, began pilot training

Early 1943 — Earned his wings, flew stateside until England transfer

November 1943 — Began flying P-51 Mustangs against Luftwaffe

March 1944 — On his 8th mission, shot down Me-109 fighter and He-111K bomber before being shot down over France.

Late spring 1944 — Returned to England after escape with help of French resistance.

Summer 1944 — Flew 56 combat missions, shooting down 11 more German aircraft, including five Messerschmidt 109s in one day, and four on another

July 1945 — Tested P-80 Shooting Star and P-84 Thunder jet fighters at Wright Field, Ohio. Also flew and evaluated captured German and Japanese fighter aircraft

August 1947 — Arrived at Muroc Army Air Corps Base (now Edwards) as Air Force project officer on Bell X-1 rocket research aircraft

Oct. 14, 1947 — Flew the X-1 beyond the speed of sound at the age of 24

June 10, 1948 — U.S. government finally announces first Supersonic Flight.

1953 — Flew the Bell X-1A to twice the speed of sound, Mach 2.435, and then saved the aircraft when it went out of control, safely landing it

1954-1957 — Commanded 417th Fighter-Bomber Squadron (50th Fighter-Bomber Wing) at Hahn AB, West Germany

1957 — Toul-Rosieres AB, France

1957-1960 — Commanded F-100D Super Sabre-equipped 1st Fighter Day Squadron, George AFB, Victorville, Calif., and Morón AB, Spain

1961 — Completed yearlong studies at Air War College. Thesis on short takeoff and landing aircraft.

1962 — Became first commandant of the renamed U.S. Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School, preparing future astronauts for NASA and the Air Force

Dec. 10, 1963 — Became first pilot to eject in a full pressure suit after rocket-assisted NF-104 he was testing went into a flat spin nearly 21 miles above earth. He sustained burns from the ejection

1966 — Commanded 405th Tactical Fighter Wing, Clark AB, Philippines, deploying on rotational duty in South Vietnam and other locations. Flew 127 combat missions

February 1968 — Commanded 4th Tactical Fighter Wing, Seymour Johnson AFB, N.C., and led F-4 Phantom II wing in South Korea during Pueblo crisis

1969 — Promoted to brigadier general and assigned as vice commander of 17th Air Force

1971-1973 — At request of U.S. ambassador, assigned as adviser to Pakistani Air Force. Beechcraft assigned to Yeager by the Pentagon was damaged in air raid on Pakistani airbase during 1971 war with India. Yeager complained the Indian pilot was instructed to attack his plane, saying it was, “the Indian way of giving Uncle Sam the finger.”

June 1973 — Named Director of the Air Force Inspection and Safety Center at Norton AFB, Calif.

March 1975 — Following assignments in Germany and Pakistan, retired from the Air Force at Norton AFB, Calif.

1986 — Appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the National Commission on Space and the team of investigators into the cause of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

Oct. 14, 1997 — On 50th anniversary of first Mach 1 flight, he flew a new Glamorous Glennis III, an F-15D Eagle past Mach 1. Chase plane pilot in F-15 Fighting Falcon was test pilot Bob Hoover, who was Yeager’s wingman for the first supersonic flight. At the end of his speech to the crowd in 1997, Yeager concluded, “All that I am; I owe to the Air Force.”